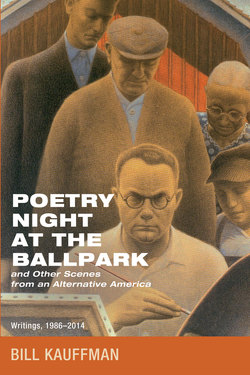

Читать книгу Poetry Night at the Ballpark and Other Scenes from an Alternative America - Bill Kauffman - Страница 39

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

I Clean My Gun and Dream of Galveston

ОглавлениеThe American Conservative, 2012

Is there a better antiwar pop song than “Galveston,” which Jimmy Webb wrote and Glen Campbell sang in the Vietnam-hued year of 1969? Therein, a young soldier daydreams of his Texas home by the Gulf and the girl he left behind. He describes the things he misses—“seawaves crashing,” “seabirds flying in the sun”—and confesses that “I am so afraid of dying” without seeing girl or Galveston again.

There is not a single note of preachiness or abstraction in the song. Yet in elevating home over foreign crusades, “Galveston” borders on sedition. It really ought to be banned under the Patriot Act.

I had hoped that Glen Campbell would sing “Galveston” when I saw him in concert at the University of Buffalo in the waning days of his morbidly (and accurately) titled “Goodbye Tour.” He did not disappoint—though he did forget the name of the composer, turning to his banjo-playing daughter (who looks like a young Laura Dern) and asking, “Who wrote this?”

Such are the spontaneities when live performance intersects with Alzheimer’s disease.

There’s been a load of compromisin’ on the road to Glen’s horizon. It’s a long, long trail a-winding from Delight, Arkansas, to the Malibu Country Club. Aside from his signature song, the John Hartford-penned “Gentle on My Mind,” and those achingly lonesome Webb-Campbell collaborations—“Wichita Lineman,” “By the Time I Get to Phoenix,” “Galveston”; Jimmy Webb understood location, location, location—Glen Campbell churned out his share of schlock. He also made the worst acting debut in the history of cinema in the John Wayne version of his fellow Arkansan Charles Portis’s True Grit. (Portis, Campbell, Johnny Cash, Levon Helm, Senator Fulbright—Arkansas gave America a lot more than America ever gave Arkansas. A priapic president excepted, of course.)

In his daily life, by all accounts, Glen Campbell could be ungentle and mindless. But hey, “Wichita Lineman” is, as Creem declared, “one of the most perfect pop records ever made,” and Campbell cut a beautiful Christmas album which my mom played throughout all my childhood Decembers. That’s worth something; it’s worth more than something.

The mood of the milling preconcert crowd was somber, even funereal. The world is fading out of focus for Glen Campbell, a little more each day, and there was a hint of voyeurism about the whole enterprise. Dementia is seldom a hot ticket. Surely this show would fall somewhere between heartwarming and wince-inducing.

Campbell was never as cool as, say, Johnny Cash or John Doe or John Fogerty, but nor was he a lounge lizard or muzak-maker. I had assumed that the audience would be a mix of hipsters and the elderly, but hipsters were vastly outnumbered by hip replacements.

(Speaking of which, the title song of Campbell’s haunting valedictory album “Ghost on the Canvas” was written by Paul Westerberg of the late great Minneapolis punk band The Replacements. October turned out to be Replacements month in our family. Two weeks earlier, while on a tour of the nineteenth-century Hudson River School painter Frederic Church’s Persian-style redoubt Olana, I had noticed—how could I not?—that one member of our group was clad in leather and chains. He was strolling the grounds with his wife and his parents. His mom proudly wore a hoodie bearing his name and image: it was Tommy Stinson, another Replacement. When an old lady asked Mrs. Stinson about the silhouette on her sweatshirt, she beamed. “That’s my son. He’s a musician.” Aren’t proud moms great?)

Glen’s voice was rough, and despite a stage ringed with monitors he fumbled lyrics. But his fingers remembered the chords, and the filial cast of his band, which included two sons and a daughter (all from his fourth wife), seemed a real comfort to a man who in his most lucid moments must see premonitions of blackness and blankness. When his daughter good-naturedly interrupted Campbell as he started to play a song he’d finished playing a minute earlier, he grinned and said, “That’s why I brought my kids up good.”

After barely more than an hour, Campbell closed the concert with “A Better Place,” a simple and lovely song he wrote for his final album. Backed by his children, he sang:

Some days I’m so confused, Lord

My past gets in my way

I need the ones I love, Lord

More and more each day

Glen Campbell ended his last song with a promise that “A better place awaits/You’ll see.” Then his daughter took him by the hand and led him from the stage, into the darkness.