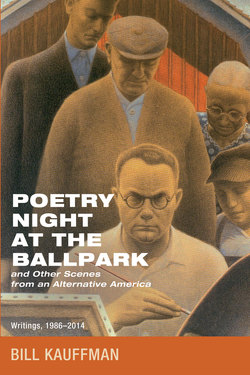

Читать книгу Poetry Night at the Ballpark and Other Scenes from an Alternative America - Bill Kauffman - Страница 26

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Vonnegut’s Cradle

ОглавлениеFirst Principles, 2009

Kurt Vonnegut, Armageddon in Retrospect, with an introduction by Mark Vonnegut (New York, NY: Putnam, 2008), 232 pp.

All my jokes are Indianapolis. All my attitudes are Indianapolis. My adenoids are Indianapolis. If I ever severed myself from Indianapolis, I would be out of business. What people like about me is Indianapolis.

—Kurt Vonnegut, 1986

In the recent “Regionalism” special issue of the University Bookman, Jeremy Beer, Hoosier boy, ranked Kurt Vonnegut second (behind Booth Tarkington but ahead of Ross Lockridge Jr. and Theodore Dreiser) in Beer’s Genuinely Objective Rankings of Indiana Authors, Twentieth Century Division.

Seeing the silver medal hanging ’round Vonnegut’s neck gave me a bit of a start. Not that I disagree with Beer’s assessment—though I’d transpose Vonnegut with Lockridge, the most tragic of America’s one-book novelists, who two months after publication of his Whitmanesque Raintree County (1948) sucked carbon monoxide in his garage till he was dead. (An unfounded rumor that I wish were true had it that he died listening to the Indiana high-school basketball tournament on the car radio.)

But Kurt Vonnegut’s inclusion seemed strange because he wore the scarlet letters SF, and other than Ray Bradbury of Waukegan, Illinois, we seldom think of science-fiction writers as tied to any particular place, at least any place smaller than a planet. Billy Pilgrim, the wanderer in Vonnegut’s best novel, Slaughterhouse-Five (1969), became “unstuck in time,” and the science-fiction shelves in any library would be a lot thinner if the authors and characters thereon had not also become unstuck in place.

Armageddon in Retrospect, a posthumous collection of previously unpublished writings on war and peace, confirms Jeremy Beer’s judgment: Kurt Vonnegut, whatever else he was, was Indianan, not Tralfamadorian. As this product of James Whitcomb Riley School once said, “I trust my writing most and others seem to trust it most when I sound most like a person from Indianapolis, which is what I am.”

He sure was. Kurt Vonnegut Jr. was born into a wealthy family, certainly by Indianapolis standards—a magnificent Amberson, of a sort, though the sources of that soon-to-dissipate wealth were buildings on his paternal side and beer on his mother’s.

Vonnegut wrote about his lineage in Palm Sunday (1981), noting with pleasure that in his genealogical digging “I find no war lovers of any kind.” In between one-liners he also discussed his bloodline in his final speech, which he wrote for the Year of Vonnegut, a joint undertaking of various community organizations in his hometown. Vonnegut died two weeks before he was to have given the talk, which was then delivered on April 27, 2007, by his son Mark at Clowes Hall at Butler University and which is reprinted herein.

From the grave, as it were, Vonnegut spoke with pride of his forebears and their accomplishments: the Vonnegut Hardware Company of Clemens Vonnegut Sr.; the architecture of Kurt Vonnegut Sr. and Bernard Vonnegut, the novelist’s grandfather, whose works included a locally famous department store clock. Their descendant, or his shadow, told the gathering that “my grandfather, the architect Bernard Vonnegut, designed, among other things, The Athenaeum, which before the First World War was called ‘Das Deutsche Haus.’ I can’t imagine why they would have changed the name to ‘The Athenaeum,’ unless it was to kiss the ass of a bunch of Greek-Americans.”

Actually, he knew all too well the reason. The name change and the many other manifestations of anti-German hysteria during the War to End All Wars disgusted Vonnegut, as did his parents’ willingness “to make me ignorant and rootless as proof of their patriotism.” But there were to be more egregious crimes committed later against his family’s handiwork. Referring to his hometown’s disastrous episodes in urban renewal, Vonnegut once said: “‘Renew’ is the wrong term, of course. What the city does is architecturally destroy itself. It cannibalizes the types of graceful and delicate architecture that made it a thing of beauty. So I guess there was something harrowing for my father: existing in a city, a provincial capital like Indianapolis, witnessing the systematic replacement of works of art, many of which he helped create, with a bunch of amorphous cinder blocks.”

Vonnegut was conscious of his link to an earlier generation of Hoosier writers. “With the passage of time,” he wrote in his Butler speech,

[N]obody will know or care who [Booth] Tarkington was. I mean, who nowadays gives a rat’s ass who Butler was? This is Clowes Hall, and I actually knew some real Clowses. Nice people.

But let me tell you: I would not be standing before you tonight if it hadn’t been for the example of the life and works of Booth Tarkington, a native of this city. During his time, 1869 to 1946, which overlapped my own time for twenty-four years, Booth Tarkington became a beautifully successful and respected writer of plays, novels, and short stories. His nickname in the literary world, one I would give anything to have, was ‘The Gentleman from Indiana.’

When I was a kid, I wanted to be like him.

We never met. I wouldn’t have known what to say. I would have been gaga with hero worship.

Yes, and by the unlimited powers vested in me by Mayor Peterson for the entire year, I demand that somebody here mount a production in Indianapolis of Booth Tarkington’s play Alice Adams.

A nice gesture, that. Tarkington was a great American novelist whose Growth trilogy, the centerpiece of which is his masterpiece The Magnificent Ambersons (1918), is as out of fashion as the pince-nez and the Tenth Amendment. His rediscovery, if only—especially—in his native ground, would be a blessing. But Vonnegut’s conjuration of his literary landsman raises a prickly point.

To wit: In his last interview, with the leftist magazine In These Times, Vonnegut said, “[E]veryone needs an extended family. The great American disease is loneliness. We no longer have extended family. But I had one. . . . I was surrounded by relatives all of the time. You know, cousins, uncles and aunts. It was heaven. And that has since been dispersed.”

The passive voice here carries the hint of self-exculpation. Vonnegut chose to spend his adulthood in Cape Cod and then on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, a celebrity in precincts quite alien to his native ground. His hero Tarkington, by contrast, had stayed in Indianapolis. One wonders—at least I wonder—if the marked inferiority of Vonnegut’s later work was due, in part, to his immurement in that gilt sepulcher of American fiction, that anti-Indianapolis, Manhattan.

Though uprooted, Vonnegut at his best charted his course using the lodestars of his boyhood. Indianapolis-bred Gregory Sumner, who is writing a Vonnegut biography, quotes his subject:

[E]verything I believe I was taught in junior civics during the Great Depression—at School 43 in Indianapolis, with full approval of the school board. . . . America was an idealistic, pacifistic nation at that time. I was taught in the sixth grade to be proud that we had a standing Army of just over a hundred thousand men and that the generals had nothing to say about what was done in Washington. I was taught to be proud of that and to pity Europe for having more than a million men and tanks. I simply never unlearned junior civics. I still believe in it. I got a very good grade.

That ingrained antimilitarism perfuses Armageddon in Retrospect, whose first piece is a May 29, 1945, letter from the author to his family, explaining that “I’ve been a prisoner of war since December 19th, 1944.” For once there are no jokes, only a terse narrative of his boxcar trip to the POW camp: “The Germans herded us through scalding delousing showers. Many men died from shock in the showers after ten days of starvation, thirst and exposure. But I didn’t.”

Prisoner Vonnegut endured the trip only to witness the February 1945 destruction of Dresden by Allied bombs, an experience on which he would draw to write Slaughterhouse-Five and other fiction, including pieces in this book. In Dresden, writes Vonnegut, “were the symbols of the good life; pleasant, honest, intelligent. In the Swastika’s shadow those symbols of the dignity and hope of mankind stood waiting, monuments to truth. The accumulated treasure of hundreds of years, Dresden spoke eloquently of those things excellent in European civilization wherein our debt lies deep. I was a prisoner, hungry, dirty, and full of hate for our captors, but I loved that city and saw the blessed wonder of her past and the rich promise of her future.”

Private Vonnegut survived the bombing in a slaughterhouse meat locker. In its aftermath, he and his fellow captives were ordered to wade ankle deep in “an unsavory broth” of viscera searching out the dead, whom they found in charred pieces. “Civilians cursed us and threw rocks as we carried bodies to huge funeral pyres in the city,” he writes, until the impossibility of transporting that many corpses and limbs became apparent and the job was turned over to men with flamethrowers who “cremated them where they lay.”

This didn’t square with those civics lessons learned in the public schools of Indianapolis. Without ever losing sight of the evil of the Nazi regime, Vonnegut declares, “The killing of children—‘Jerry’ children or ‘Jap’ children, or whatever enemies the future may hold for us—can never be justified.”

(Not included in this volume is a prewar editorial from the Cornell Daily Sun in which Vonnegut, true to his Midwestern pacifist roots, defended the most controversial isolationist of the day: “Charles A. Lindbergh is one helluva swell egg, and we’re willing to fight for him in our own quaint way. . . . The mud-slingers are good. They’d have to be to get people hating a loyal and sincere patriot. On second thought, Lindbergh is no patriot—to hell with the word, it lost it’s [sic] meaning after the Revolutionary War. . . . The United States is a democracy, that’s what they say we’ll be fighting for. What a prize monument to that ideal is a cry to smother Lindy.”)

Several of the stories in Armageddon in Retrospect concern American POWs in 1945 Germany: Vonnegut territory. Typical is the character who is so hungry that “if Betty Grable had showed up and said she was all mine, I would have told her to make me a peanut butter and jelly sandwich.” These are, for the most part, decent men, believers in the verities, who find themselves in a topsy-turvy world in which collaborators and snitches are the top rails. What’s an Indiana Boy Scout to do? Refuse. Resist. Laugh. Vonnegut said that his afflatus—the reason “stuff came gushing out” of him—was “disgust with civilization.” But he was not a misanthrope, just a man who never lost his capacity for righteous outrage. Wars, he believed till the end of his life, are hell and the negation of all that Jesus taught. The draft-dodgers and chickenhawks who lie and drag us into them should be boiled in that viscera broth.

About Jesus. Descended of a long line of freethinkers, Vonnegut, a self-described “Christ-worshipping agnostic,” was a nonbeliever who respected, even praised, varieties of religious belief. He knew that sniping at religion can become tiresome. You need village atheists—you just don’t want atheist villages. Vonnegut’s doodles and doggerel decorate the book; among them is this apothegm, above a skull and crossbones: “Darwin gave the cachet of science to war and genocide.”

Vonnegut sometimes called himself a socialist. My late friend Barber B. Conable Jr., long-time ranking member of the House Ways and Means Committee, told me that every now and then his old Cornell classmate lobbied him for better tax-law treatment of authors. Even socialists resent the IRS, I guess.

On that note, the collection includes an amusing anarchist fable (“The Unicorn Trap”) about an honest serf and his harpy wife arguing over the husband’s potential elevation to tax collector for Robert the Horrible. Their exchange:

“If a body gets stuck in the ruling classes through no fault of their own,” she said, “they got to rule or have folks just lose all respect for government.” She scratched herself daintily.

“To their sorrow,” said Elmer.

“Folks got to be protected,” said Ivy, “and armor and castles don’t come cheap.”

They still don’t, Ivy.

***********

Vonnegut once asked his son Mark, “Does anyone out of high school still read me?”

I hadn’t in many years. As a teenager I played the usual Slaughterhouse-Five to Breakfast of Champions to Player Piano/Cat’s Cradle combination, after which the enthusiasm fizzles. Happy Birthday, Wanda June? Slapstick? I cringe to recall. Vonnegut wrote some bad books, but he wrote some very good ones, too. In our age of an America perpetually at war, he is, perhaps, more necessary than ever.

The U.S. invasion of Iraq, writes Mark, “broke his heart not because he gave a damn about Iraq but because he loved America.” His crest fell; didn’t anyone else believe those civics lessons? “It wasn’t until the Iraq War and the end of his life that he became sincerely gloomy.”

The last piece of advice Kurt Vonnegut ever offered was this: “We should be unusually kind to one another, certainly. But we should also stop being so serious. Jokes help a lot. And get a dog, if you don’t already have one.”

You got a better idea?