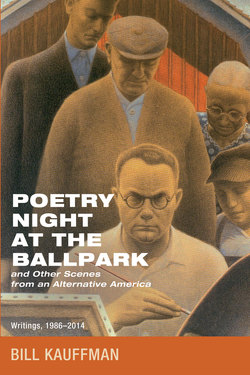

Читать книгу Poetry Night at the Ballpark and Other Scenes from an Alternative America - Bill Kauffman - Страница 35

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The Last Republican

ОглавлениеThe American Conservative, 2008

The Selected Essays of Gore Vidal, edited by Jay Parini (New York: Doubleday), 458 pages, $27.50

“Gore Vidal is America’s premier man of letters,” says Jay Parini in his introduction to The Selected Essays of Gore Vidal, and if after reading Vidal on William Dean Howells, Tennessee Williams, various dead Kennedys, and “American sissy” Theodore Roosevelt the reader denies it—well, hie on back to the MFA prison.

The Selected Essays were written over the course of a half-century (1953–2004), or almost one-quarter of the lifespan of the republic that is Vidal’s primary subject—though it might more accurately be said that Vidal has been a contumacious patriot of the Old Republic for nigh the entirety of the post-republic era. As such he is a man out of time in the United States of Amnesia, as he calls his native and beloved land.

What a pleasure these essays are. One imagines Gore Vidal at his writing desk, hint of a smile creasing his mouth as he mints Saint-Gaudens gold piece-quality-witticisms with Lincoln penny-like frequency. Here he is on Ohio’s greatest novelist: “For a writer, Howells himself was more than usually a dedicated hypochondriac whose adolescence was shadowed by the certainty that he had contracted rabies which would surface in time to kill him at sixteen. Like most serious hypochondriacs, he enjoyed full rude health until he was eighty.”

“It should be noted that Vidal is conservative in many respects,” writes Parini. “He stands behind individual choice, the limitation of executive power, and preservation of the environment. Like his grandfather, he dislikes the empire . . . He would return us, if possible, to the pure republicanism of early America.”

That grandfather, the blind Senator Thomas P. Gore (D-OK), was a first-rate populist foe of war and FDR. He was a peace Democrat, which is why no one has ever heard of him. Vidal’s education owed more to home than academy, as he read aloud to the senator, from whom he inherited an isolationist opposition to foreign wars, a populist suspicion of concentrated capital, a freethinker’s hatred of cant, and a patriot’s detestation of empire.

Like Mencken, Ray Bradbury, Hemingway, and other original Americans, Vidal escaped a college sentence. He is the scourge of sciolism, of credentialed arrogance. As he writes of his friend’s mistreatment while speaking to snotty drama students at Yale: “Any student who has read Sophocles in translation is, demonstrably, superior to Tennessee Williams in the unruly flesh.”

The foaming and thoroughly ideologized haters of Vidal are simply incapable of writing prose anywhere near as tautly conversational, as confidently but never pedantically erudite, as amaranthine as the master. Vidal commits an unforgivable sin in our age of the national Hall Monitor: humor. Is it any wonder they hate him? Vidal inevitably gets the best of the carpers in any exchange, because he is funny and they are not. Or in his words, “I responded to my critics with characteristic sweetness, turning the other fist as is my wont.”

His best essays are often sympathetic readings of such forgotten or undervalued American writers as the Ohio (Ohio again!)-bred satirist Dawn Powell (who “always knows how much salt a wound requires”); Tarzan creator Edgar Rice Burroughs (a talented action writer who was “innocent of literature” but as a drifter, cowboy, gold miner, and railroad cop was, like Vidal, “perfectly in the old-American grain”); and Tennessee Williams, “the Glorious Bird,” whose work Vidal assesses with affectionately critical eye. The personal anecdote he deploys expertly. Of a dinner with Williams and his magnificently termagant mother:

Tennessee clears his throat again. “Mother, eat your shrimp.”

“Why,” counters Miss Edwina, “do you keep making that funny sound in your throat?”

“Because, Mother, when you destroy someone’s life you must expect certain nervous disabilities.”

One of my favorite Vidal essays is his appreciation of William Dean Howells, who brought Ohio into the Atlantic Monthly and championed the new realists and regionalists of the late Gilded Age. He is a man after Vidal’s own heart: “Since Howells had left school at fifteen he had been able to become very learned indeed.”

Howells was barely of shaving age when he wrote a campaign biography of Lincoln. Precocious, “an ambitious but not insane poet,” he obtained a consulate in Venice thanks to his connection with Salmon P. Chase, the Free Soil Buckeye and constitutionalist who as Lincoln’s Secretary of the Treasury and later Chief Justice of the Supreme Court is one of those men, like Robert A. Taft and Bob La Follette, who really ought to have been president.

Howells later wrote another campaign biography, this time of Rather-fraud Hayes, for whom the 1876 election was stolen from Samuel Tilden, the pornography connoisseur known in real-estate circles as “The Great Forecloser,” but Howells’s legacy was one of the truly great American novels, The Rise of Silas Lapham (1885). Again, the subject is vivified through a close reading of the novels and perfectly placed anecdotes.

There is, I suppose, a sense in which a eulogist often is singing a song of himself. We laud in others what we perceive, or hope for, in ourselves. Vidal says of Howells that he “wrote a half-dozen of the Republic’s best novels. He was learned, witty, and generous.” Just so with the eulogist.

Likewise, Vidal is fond of his kindred spirit Edmund Wilson, also a proprietary patriot. The country was founded by such as Vidal and Wilson, their people shaped it, and they will not let it go without a fight, which is why in its collapse they turned withering fire upon its enemies. Wilson and Vidal were brave, though it was really a sense of patriotic duty, I think, that impelled their lonely stands against the empire that was erasing their ancestral republic.

Wilson (“the most interesting and the most important” critic of midcentury) was a polymathic old American autodidact (Princeton years excluded) of the Vidal school: “When he died, at seventy-seven, he was busy stuffing his head with irregular Hungarian verbs.” Vidal appreciates Wilson in his late autumn, when he really hit his stride with Patriotic Gore (whose introduction, comparing Lincoln to Lenin and Bismarck, got the energetic Bunny expelled from the warren), The Cold War and the Income Tax, Upstate, and Apologies to the Iroquois.

Also like Wilson, Vidal regards federal taxes as confiscatory and the fuel by which an anti-American war machine is run. “Why,” he asks in his 1972 essay “Homage to Daniel Shays,” “do we allow our governors to take so much of our money and spend it in ways that not only fail to benefit us but do great damage to others as we prosecute undeclared wars—which even our brainwashed majority has come to see are a bad proposition because of the cost of maintaining a vast military machine, not to mention a permanent draft of young men (an Un-American activity if there ever was one) in what is supposed to be peacetime? Whether he knows it or not, the middle-income American is taxed as though he were living in a socialist society.” In 1951, most self-described “conservatives” would have nodded their heads in agreement with this observation. But that was before the “conservative movement” sacrificed hearth, home, peace, liberty, and tenderness on the block to wars without end and tanks with 501(c)(3) tread.

Vidal dislikes Wilson’s clinical diaristic record of his sexual irruptions. “In literature, sexual revelation is a matter of tact and occasion,” writes Vidal, who, contrary to the idiotic canard that he is a “gay writer,” has written about his own sex life sparingly. He is impatient with those modern writers who, once they “could put sex into the novel, proceeded to leave out almost everything else.” He is what he calls a same-sexer, though where sex intercrops with politics he is libertarian, demanding only that the state leave adults alone to pursue whatever consensual conjugations they please.

He disdains the hatchet, though no one levels the critical boom quite as crushingly, in a single sentence, as Gore Vidal. Of John Updike’s memoir Self-Consciousness (1989): “Dental problems occupy many fascinating pages.” Of Herman Wouk’s The Caine Mutiny (1951): “from Queequeg to Queeg, or the decline of American narrative.” Reviewing Donald Barthelme’s Guilty Pleasures (1974): “This writer cannot stop making sentences. I have stopped reading a lot of them.” (This is in the midst of a hilarious essay based on voluntary exposure to the academy-bound American metafictionists, who provide “the sense of suffocation one experiences reading so much bad writing.”)

The inevitable Arthur Schlesinger, ineligible receiver in those Kennedy touch football games, is noticed and dismissed: “A Thousand Days is the best political novel since Coningsby.” Unlike “Professor Pendulum,” who fretted over the imperial presidency only when Richard Nixon darkened the White House, Vidal, as a good Anti-Federalist, views the president, whether Democrat or Republican, as “a dictator who can only be replaced either in the quadrennial election by a clone or through his own incompetency.” Executive orders, executive agreements, executive privileges: he would scrap them all. He admires the Swiss cantonal system and would borrow from it to revive our torpid federalism. He favors national referenda, a pet cause of his grandfather, one of the first proponents of the war referendum that later took shape as the Ludlow Amendment. He would “stop all military aid to the Middle East,” repeal “every prohibition against the sale and use of drugs,” and “withdraw from NATO.”

He is very much in the American libertarian vein, though his conviction that “monotheism is the greatest disaster ever to befall the human race” is unlikely to appeal to many conservative readers. He is a Bill of Rights stalwart, however, who takes the now wildly unfashionable view that kooks and outcasts have liberties, too. These include the Branch Davidians, who “were living peaceably in their own compound at Waco, Texas, until an FBI SWAT team . . . killed eighty-two of them.” As early as 1953 he spoke of “these last days before the sure if temporary victory of that authoritarian society which, thanks to science, now has every weapon with which to make even the most inspired lover of freedom conform to the official madness.”

He patriotically detests the National Security State, which hijacked the country circa 1950 and has not given up the controls yet. In the late 1980s Vidal called for a “neo-Clayite” candidate to campaign on internal improvements and avoidance of foreign quarrels. I wish he had run the race himself. But by 1992, three such men were running: Ross Perot, Jerry Brown, and Pat Buchanan, in the most interesting political year of the post-republic era. Each, in his particular way, appealed to heirs and offshoots of the old Thomas P. Gore/Bob LaFollette/America First populist tradition. Vidal sensed a “potentially major constituency—those who now believe that it was a mistake to have wasted, since 1950, most of the government’s revenues on war.” He scorned Buchanan’s Catholic understanding of sexuality but conceded that “he is a reactionary in the good sense—reacting against the empire in favor of the old Republic, which he mistakenly thinks was Christian.”

Every now and again the reader is reminded that Vidal’s bloodlines run south. He chides G. William Domhoff, who is “given to easy liberal epithets like ‘Godforsaken Mississippi’” even though “except on the subject of race, the proud folk down there are populist to the core.” So is Vidal. He is with Shays, with Bryan, with the America Firsters. He envisages an alliance of the “not-so-poor” and the poor and predicts that the “politician who can forge that alliance will find himself, at best, the maker of a new society; at worst, in a hole at Arlington.”

While his subject has been America and the push-pull debate over its empire, Vidal rejects novels “which attempt to change statutes or moral attitudes” as “not literature at all” but arid propaganda. Thus he is capable of the greatest fictive rendering of Abraham Lincoln in all of American literature—the novel Lincoln (1984)—despite being largely out of sympathy with Lincoln’s politics. For Vidal desires the president to be cut down to constitutional size, and Lincoln, he writes, “levied taxes and made war; took unappropriated money from the Treasury; suspended habeas corpus.”

Yet Lincoln, that most confounding of presidents, was also thoughtful, wise, and an erstwhile critic of expansion. His old law partner Billy Herndon claimed that Abe never read a book straight through, but at least he did not make fun of book-writers. The contrast with the current warmaker in the White House reflects well on the nineteenth century, or poorly on us.

And so I must end with a lovely and poignant passage from Vidal’s Howells essay. It is the kind of vignette that would appeal only to a man with a country:

For some years I have been haunted by a story of Howells and that most civilized of all our presidents, James A. Garfield. In the early 1870s Howells and his father paid a call on Garfield. As they sat on Garfield’s veranda, young Howells began to talk about poetry and about the poets that he had met in Boston and New York. Suddenly, Garfield told him to stop. Then Garfield went to the edge of the veranda and shouted to his Ohio neighbors, “Come over here! He’s telling about Holmes, and Longfellow, and Lowell, and Whittier!” So the neighbors gathered around in the dusk; then Garfield said to Howells, “Now go on.”

Today we take it for granted that no living president will ever have heard the name of any living poet. This is not, necessarily, an unbearable loss. But it is unbearable to have lost those Ohio neighbors who actually read books of poetry and wanted to know about the poets.

Thus speaks Gore Vidal, America patriot.