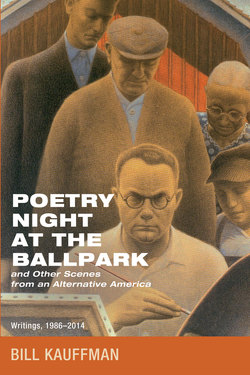

Читать книгу Poetry Night at the Ballpark and Other Scenes from an Alternative America - Bill Kauffman - Страница 29

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Shelter from the Storm

ОглавлениеThe American Conservative, 2010

The week that Wisconsin voters threw out Russ Feingold, the only stepgrandson Fighting Bob La Follette had left in the U.S. Senate, I went to hear an Upper Midwesterner of similar pedigree, Bob Dylan of Hibbing, Minnesota.

I actually saw some heads without hoarfrost, a pleasing contrast to the last time I paid a column’s wages to sit in a hockey arena and listen to music. When my brother and I attended a Bruce Springsteen concert a couple of years ago, we surveyed the crowd and figured we must have wandered into a tour stop by the Ray Conniff Singers.

Lord knows I loved Bruce back in the Darkness on the Edge of Town/Nebraska days, after he had shed his early Dylan mimicry and set out to be the John Steinbeck of Freehold, New Jersey. My buddy Chuck and I would snake around town in his old jeep yowling, “If she wants to see me/You can tell her that I’m easily found. . . .” Unfortunately, while we were easily found, she sure didn’t want to see us.

Politically, Bruce was nowhere near as interesting as the early punks or even that Mormon-Jewish hybrid Warren Zevon. (From Crystal Zevon’s warts-aplenty 2007 portrait of her ex-husband, I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead, comes this account of the Zevons’ child-custody dispute: “Warren got on the phone; he was obviously drunk. . . . He said, ‘I’m to the right of your father and Ronald Reagan and if you think I’m going to let my daughter be raised by some fucking Communist hippie, you’re sadly mistaken.’” But really, who can resist a songwriter who begins a lyric, “I went home with the waitress/The way I always do/How was I to know/She was with the Russians, too?”)

Dylan, on several other hands, has been a Goldwater admirer, born-again Christian, and proponent of agrarianism as the “authentic alternative lifestyle.” He was formed in Minnesota before he ever saw Greenwich Village. In his memoir Chronicles, the singer, mindful of his roots in that frozen ground, writes of Charles Lindbergh, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Eddie Cochran, Sinclair Lewis, and Roger Maris as men he “felt akin to,” freethinking sons of the North Country who “followed their own vision, didn’t care what the pictures showed them.”

Lindbergh’s congressman father, whom the New York Times tagged the “Gopher Bolshevik,” was a fierce critic of Wall Street, Woodrow Wilson, and the war machine. Charles Lindbergh Sr. was a progenitor of a vigorous Minnesota antiwar tradition that found expression in men such as Senators Henrik Shipstead and Eugene McCarthy before degenerating into the boring Cold War social democracy of Hubert Humphrey and Walter Mondale or the Republican polenta of Pawlenty.

Bob Dylan is very much in the Lindbergh-McCarthy tradition, as Norwegian academic Tor Egil Forland explained in a 1992 Journal of American Studies paper titled “Bringing It All Back Home or Another Side of Bob Dylan: Midwestern Isolationist.” But then Dylan is sixty-nine, and old enough to remember when the people of his place looked askance at empire. There were giants in the earth in those days.

When the Masters of War (“even Jesus would never forgive what you do”) requested the presence of American sons at the blood orgies of 1917, 1941, 1950, and 1964, it was the Upper Midwest, with its Non-Partisan Leagues and retro-Progressives and Sons of the Wild Jackass, that brayed “No!” Where are their offspring? I don’t mean to be impertinent or importunate, Dakotas and Minnesota and Wisconsin, but we look to you for La Follettes and Nyes and McGoverns and you give us Al Franken and Ron Johnson?

Turn off the goddam television, would you please, and turn on Wisconsin!

Feingold had his flaws but he was the only member of the Senate with the guts to vote against the Patriot Act; as Jesse Walker of Reason writes, he also “voted against TARP, was decent on the Second Amendment, and was one of the rare liberals to reach out to the Tea Parties instead of demonizing them.” He was neither red nor blue—each a scoundrel hue.

Senator Feingold quoted Dylan in his concession speech: “My heart is not weary/It’s light and it’s free/I have nothing but affection for those who have sailed with me.” Dylan closed our concert with “Ballad of a Thin Man,” rasping, “Something is happening here/But you don’t know what it is/Do you, Mr. Jones?”

I’m no more perceptive than Mr. Jones, but one thing is all too clear: the Upper Midwest, historic home of the American peace movement, has come down with an awfully bad case of laryngitis. And it’s gettin’ dark—too dark to see.