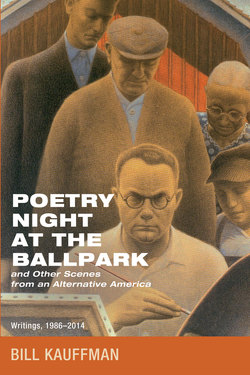

Читать книгу Poetry Night at the Ballpark and Other Scenes from an Alternative America - Bill Kauffman - Страница 37

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Friendly Ghosts

ОглавлениеThe American Conservative, 2009

Ours is an October house, shrouded by spreading maples. Its creaky floorboards of pine and chestnut were hewn in the 1830s, as Upstate New York was ablaze with the religious and reform manias through which we earned the appellation of the “Burned-Over District.” Ancient spiderwebs lattice the basement. (I really should knock them down, but then where would the ancient spiders live?) The previous owner, a willowy eccentric, assured us that “pixies and fairies frolic in the garden,” but aside from a few house guests, I’ve yet to see that. Nor have I seen a ghost, even though for nigh unto a century our county’s leading spiritualists called this their earthly home.

When we moved in seventeen autumns ago, my wife and I read aloud Dracula. The only other auditor was our lab-mutt puppy, who, thus forewarned, never did become a biter. (When our infant daughter came home from the hospital two winters later, I walked her to sleep to Cormac McCarthy’s All the Pretty Horses. Okay, so it’s not Goodnight, Moon, but at least it ain’t Blood Meridian.)

My parents order the same breakfasts at the same diners on the same days every single week, and I suppose I have inherited this orderliness in my seasonal reading habits. Come October, I take the same old friends off the bookshelf. I could no more grow tired of them than I could be bored by the resplendent reds and oranges of an Upstate fall.

First up is always Stephen Vincent Benet’s The Devil and Daniel Webster, in which the Godlike Dan’l defends a New Hampshireman who has sold his soul to Scratch. (No, it wasn’t David Souter.) As my daughter and I read it this year, I thought about Webster, re-elected to Congress in 1814 on the “American Peace Ticket”—a name reeking of treason in our twenty-first-century America of perpetual war. William Dieterle made a superb film of Benet’s story, but why has no movie ever been made of Webster’s gargantuan life?

We read Poe, of course, and after the House of Usher collapses into the tarn, I eye the fissure in our foundation with a certain foreboding. Irving’s “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” with its sumptuous description of a Dutch repast, confirms my taste for oly koeks (whatever they are) over Little Debbies. Next up is Nathaniel Hawthorne’s allegory “Young Goodman Brown,” in which a Salem Puritan finds—or does he?—that “There is no good on earth; and sin is but a name. Come, devil; for to thee is this world given.” The Cheney family motto, I’ll bet.

Why has no American novelist written about the strange yet fortifying friendship of Hawthorne and President Franklin Pierce? We’ve such a fantastically rich history, yet men drain away their days watching the living dead wrestle animated corpses on MSNBC and Fox.

I had approached Russell Kirk’s ghost stories with dread, fearing that on the scare-meter they’d register even lower than the supernatural tales (Turn of the Screw aside) of Henry James, in which, at most, a spinster’s petticoats are rustled by a draft. Yet Kirk’s ghostly tales, collected in Ancestral Shadows, cast a spell. I annually read “Saviourgate,” in which a harried man has a restorative whiskey and chat at a small hotel on the borderland between this world and the next; and “An Encounter by Mortstone Pond,” wherein a used-up man meets and emboldens his younger sorrowful self. There is, in Kirk’s diction and pace, a fustiness which in other writers might seem an affectation, but hey, who am I to complain about stylistic idiosyncrasies?

Here’s another book that ought to be: Ghost Stories by Reactionaries. To the finest of Kirk and James add tales (from Black Spirits and White) by the architect Ralph Adams Cram, who designed that most Octoberish of campuses, the Hudson River Gothic West Point. And throw in H.P. Lovecraft, upon whose headstone is incised one of my favorite epitaphs: “I AM PROVIDENCE.” Forget the Old Ones. The horrors of Cthulhu pale before this Lovecraft observation:

A man belongs where he has roots—where the landscape and milieu have some relation to his thoughts and feelings, by virtue of having formed them. A real civilization recognizes this fact—and the circumstance that America is beginning to forget it, does far more than does the mere matter of commonplace thought and bourgeois inhibitions to convince me that the general American fabric is becoming less and less a true civilization and more and more a vast, mechanical, and emotionally immature barbarism de luxe.

Now that is terrifying.