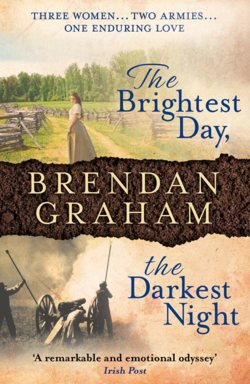

Читать книгу The Brightest Day, The Darkest Night - Brendan Graham - Страница 12

FIVE

ОглавлениеEllen slept in the Penitents’ Dormitory. About her were raised the fitful cries of other Penitents rescued from the jaws of death or, as the Sisters saw it, from a fate far worse – the jaws of Hell. For here were common nightwalkers, bedizened with sin; others sorely under the influence of the bewitching cup. Still others snatched from grace by the manifold snares of the world, the flesh and the devil. These, if truly penitent, the Sisters sought to reclaim to a life of devotion. But for now these tortured souls struggled. Redemption was not for everyone.

Penitents, those who desired it, could be regenerated. Eventually, shed of all worldly folly, their former names would be replaced by those of the saints. These restored Penitents would then be released back to secular society.

Some Penitents, drawn either by love of God, or fear of the Devil, remained, took vows, becoming Contemplatives. Continuing to lead lives of prayer and penance within the community of the Sisters.

Her own sleep no less turbulent than those around her, Ellen’s mind roved without bent or boundary. Before her, on a pale and dappled horse, paraded Lavelle. Loyal, handsome Lavelle, all gallant and smiling.

Smiling, as on the day she, with Patrick, Louisa and Mary in tow, had docked at the Long Wharf of Boston. Lavelle, with his golden hair, waiting in the sun, waving to them amid the baubled and bustling hordes on the shore. Patrick, curious about this stranger who would replace his father. Their mother’s ‘fancy man’ in America, as Patrick called Lavelle.

In the dream she saw herself laughing, this time at her doorway, talking with Lavelle. He asking a question, she saying ‘yes’ and then him high-kicking it, whistling through that first Christmas snow, down the street merrily. Then springtime … the wedding … she, taking ‘Lavelle’ for a name, relinquishing her dead husband’s name of O’Malley.

Out of the past then a nemesis – Stephen Joyce – who had delivered her first husband Michael to that early death.

Her dream changed colours then. Gone was the brightness of sun and snow … of music on merry streets. Now appeared a purpled bed. On it Stephen Joyce, book in hand reading to her. She, naked at the window, her body turned away from him. Singing to the darkly-plummed world outside … the night pulping against the window, its purple fruit oozing through the windowpane, over her body … staining her. Abruptly again, her dream had changed course. Now Stephen – dark, dangerous Stephen – he, too astride a horse, a coal-black horse, sword in hand and beckoning her. And Patrick – her dear child, Patrick – what was Patrick doing here? Giving her something … but beyond her reach. Mary and Louisa, white-winged, holding her back from going to him. Lavelle again, this time madly galloping towards them on the pale horse. Them cowering from its flashing hooves.

Frightened, she bolted upright in the bed, Louisa at her side restraining her, soothing her anxiety.

‘There, Mother, there – it’s just a bad dream, I’m with you now,’ Louisa said tenderly.

Fearfully, Ellen embraced her, afraid her adopted daughter might disappear back into the frightening dreamworld.

Louisa held her mother, until sleep finally took Ellen.

Through the New England winter began the long, slow restoration. First the temporal needs of the body. Not a surfeit of food but ‘little and often’ as Sister Lazarus advised, ‘and a decent dollop of buttermilk daily, combined with fruit – and young carrots’, for the recovery of Ellen’s eyes. ‘Common luxuries, which no doubt have not passed this poor soul’s lips since Our Saviour was a boy,’ Sister Lazarus opined.

Mary trimmed the long mane of Ellen’s hair, removing the frayed ends and straightening the raggle-taggle of knots that had accumulated there. Gradually, the pallor evaporated from Ellen’s face, a hint of rose-pink returning to her lips. Under the Sisters’ care, the physical contours of Ellen’s body began somewhat to re-establish themselves. It was not long before Louisa and Mary could both begin to see their mother re-emerge, as they had once remembered her.

‘It is the buttermilk,’ Lazarus was convinced, thankfully still showing no signs of recognition.

With Mary and Louisa’s help Ellen could now go to the Oratory for prayer and reflection. There they would leave her a while, to ponder alone. Never once did they ask about her missing years. She was grateful for that … was not yet ready to tell them. But that day would come. Perhaps early in the New Year.

Before Christmas, when she was stronger, and at Sister Lazarus’s insistence that ‘God and Reverend Mother will provide,’ Mary and Louisa took Ellen to an oculist. Years of making the Singer machines sing for Boston’s shoe bosses, had taken its toll on their mother’s eyes.

Dr Thackeray, a kindly, intent man – a Quaker, Ellen had decided, without knowing why – held his hand up at a distance from her, asking her to identify how many digits he had raised. Depending on her answer, he moved either further away or closer to her. At the end of it all he disappeared, returning at length with a stout brown bottle which he declared to contain ‘a soothing concoction’.

‘This to be poulticed on both eyes for a month of days; to be changed daily – only in darkness,’ he instructed. ‘Even then both eyes must remain fully shuttered.’ She would, he said, ‘see no human form until mine, when you return.’

He gave no indication of what improvement, if any, he expected after all of this.

During her month of darkness, Ellen’s general state of health continued to incline. She grew steadily stronger, the tone of her skin regained some former suppleness, and from Mary’s constant brushing, the once-fine texture of her hair had at last begun to return.

‘It is as much the nourishing joy at your presence, as anything Sister Lazarus’s buttermilk and young carrots might do,’ she said with delight to Mary and Louisa.

Ellen was thankful of Dr Thackeray’s poultice. That she would not have to fully face them when, at last, she told her daughters the truth; not have to look into their eyes, they into hers.

Blindness she had long been smitten with, before ever she had put first stitch into leather.

Stephen Joyce, who had ignited such debasing passions in her, was not to blame. Nor Lavelle … least of all, her ever-constant Lavelle. The blindness was solely hers – her own corroding influence on herself.

She worried about her dream and its recurrence – that by now she should have exorcised all the old devils about Stephen. Why had he appeared so threatening – sword aloft? Why the black horse and Lavelle the pale one? Good and Evil – and had they at last met? And Patrick – she unable to reach him?

Stephen first had appeared in her life in 1847. There were troubled times in Ireland – blight, starvation, evictions. Like a wraith he had come out of the night to meet with her husband Michael.

She had not interfered as rebellious plots against landlords were hatched but she had sensed tragedy. This dark man who could excite the hearts of other men to follow him, would she knew, one day bring grief under her cabin roof. And so it was. Not a moon had waned before her husband Michael, her beautiful Michael, lay stretched in the receiving clay of Crucán na bPáiste – the burial place high above the Maamtrasna Valley.

Evicted then, during the worst of the famine, and in desperation to save her starving children, she had been forced to enter a devilish pact. Her allegiance to the Big House was bought, her children given shelter. The price – her forced emigration from Ireland – and separation from them. Patrick aged ten years, Mary a mere eight. It was Stephen Joyce, the peasant agitator, scourge of the landlord class, who had come to her to guarantee their safety. Whilst she had blamed him for Michael’s death, she had, for the sake of her children, no choice but to accept his offer. Eventually, she had returned to reclaim them.

Now years later, here in America, her children had reclaimed her.