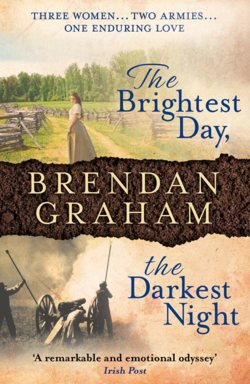

Читать книгу The Brightest Day, The Darkest Night - Brendan Graham - Страница 21

FOURTEEN

ОглавлениеInside, the limbless continued dancing unabated, and the un-whole undeterred. Now, songs were interspersed to allow some respite to the dancers, most of the songs hurled insults at the opposite side. The ‘Southern Dixie’ answered by the ‘Union Dixie’.

Way down South in the land of traitors,

Rattlesnakes and alligators …

Or, another ‘Yankee Doodle’.

Yankee Doodle said he found,

By all the census figures,

That he could starve the rebels out,

If he could steal their niggers.

Answered by

We do not want your cotton,

We do not want your slaves,

But rather than divide the land,

We’ll fill your Southern graves.

Then ‘The Irish Volunteer’ of the North clashed with ‘The Bonnie Blue Flag’ of the South. Both, Ellen recognised, sung to the same air of ‘The Irish Jaunting Car’!

The dancing resumed and Ellen was aware that Louisa was back in the midst of things. Shortly thereafter Jared Prudhomme re-appeared and Alabarmy called on him.

‘Lad, if these Yankees can’t whup us with minié balls, they ain’t gonna whup us with songs … so give us one of yer best, boy!’

Jared Prudhomme stood tall, laughed and started to sing.

‘Her brow is like the snowdrift,

Her nape is like the swan,

And her face it is the fairest,

That ’ere the sun shone on.

‘… And for Bonnie Annie Laurie

I’d lay down my head and die.’

They all liked him Ellen knew, both North and South, as did she. He was truly beautiful, in so far as one could ascribe beauty to a youth. But for all his seventeen youthful years, he had a manly bearing. Looked all straight in the eye, neither seeking favour, nor giving it. Yet with that generosity of youth that the cynicism of older age – and war – had not yet destroyed.

He sang as he looked. Clear voiced. Uninhibited by those present. Sang to ‘Annie Laurie’, as if she were there in the very room listening to him. And she was, Ellen knew, casting a glance towards Louisa. The girl’s white-bonnetted head was fixed on the boy. He did not look at her. He had no need to. The spirit within the song left his lips irrevocably bound for no other place than her.

Ellen stood transfixed. The boy reminded her so much of herself. Before she lost the gift. The gift was not the singing itself – the mere outpouring of notes – but the thing within and above the singing. She could still sing – as a person might. But the gift was lost to her. The gift came with purity – purity of intent, purity of the art itself. Letting go of desire, of ambition for the voice – the instrument – to be admired, the singer to be praised. The voice was not the gift, but the gift could inhabit the voice … but not by right or by skill alone.

The boy had the gift. Though he sang for Louisa, he did not sing to her. Then he had stopped before he had started it seemed, leaving them there suspended in the moment. The song, at one level, having passed them by. At another, having entered within, transcending them into some knowledge undefined by words or melody alone.

The listeners came back before he did. Clapped loudly, recognising that they had been transported and were now returned. ‘Arisht,’ the Irish called. ‘One more, lad!’ both friend and foe alike, echoed.

The boy just smiled, looked at Louisa, dropped his head slightly to gather himself and then looked at her again. Almost imperceptibly, she motioned her consent, the slightest tilt of her head towards him.

‘With your permission, ladies, I will dedicate this song to you all who daily raise us up.’

Acclamation arose from all those assembled. Again he looked at the ground, waiting until the burr of noise had receded.

‘When I am down and, oh my soul, so weary;

When troubles come and my heart burdened be;

Then, I am still and wait here in the silence,

Until you come and sit awhile with me.’

At the refrain, this time he looked directly at Louisa. She held his gaze, letting his sung words seep into her.

‘You raise me up, so I can stand on mountains;

You raise me up, to walk on stormy seas;

I am strong, when I am on your shoulders;

You raise me up … to more than I can be.’

All were hushed as the boy drew breath.

‘You raise me up, so I can stand on mountains;

You raise me up to walk on stormy seas;’

This time they all joined in, raising their voices in the redemptive words. A chorus of broken angels but all fear lifted from them.

‘I am strong, when I am on your shoulders;

You raise me up … to more than I can be.’

At the final line his gaze never removed from Louisa, the rapture on her daughter’s face provoking the opposite emotion in Ellen. When he finished there was again the hiatus, no one wanting to break the moment, steal wonder away.

‘We’ll give you that – you can sing you Rebs!’ Hercules O’Brien eventually ventured, nodding his block of a head in approval at the boy. Then looking at Ellen he called for ‘A soothing Irish voice to calm the storms of battle’.

She resisted, didn’t want to follow the boy, break the spell he wove. Then the boy himself called her, ‘It would do us great honour. Mrs Lavelle – a parting song. A song some may not hear again … after tomorrow.’

All knew what he meant. Some did not look at her … shuffled uneasily. Those that could – those recovered by her healing hands who, tomorrow would go out again – she could not refuse them. For some reason the pale and riderless horse flashed by her mind.

She started falteringly, sang it to the boy. Her own favourite. Favourite of all whom she loved and who in turn had loved her.

‘Oh, my fair-haired boy, no more I’ll see,

You walk the meadows green;

Or hear your song run through the fields

Like yon mountain stream …’

She looked at the boy as she sang, something fiercely ominous in her, some darker shade of meaning she had not noticed before, now present in the words.

‘So take my hand and sing me now,

Just one last merry tune …’

His clear blue eyes never left hers as she sang her tune in answer to his.

‘Let no sad tear now stain your cheek,

As we kiss our last goodbye;

Think not upon when we might meet,

My love my fair-haired boy …’

They were all her fair-haired boys, all the crippled, the crutched, the maimed and the motherless. Some called her ‘Mother’ – and even when they didn’t, she knew she was their mother in-situ, the comforting words, the tender touch.

‘If not in life we’ll be as one,

Then, in death we’ll be …’

She did not mean to sadden them with thoughts of death but to comfort them. Death indeed would come to many here … maybe to Hercules O’Brien … maybe by the hand of Ol’ Alabarmy, his dancing partner. Perhaps death would dance with the shy Rhinelander. He had danced with her, as if it were the last waltz on this wounded earth. Or death could call time on the young fiddle player from East Tennessee. Or even, Ellen kept her eyes on the beautiful boy, to Jared Prudhomme, in love with her Louisa … and she with him.

How, Ellen wondered, could anything other than the boy’s death solve Louisa’s dilemma?

‘And there will grow two hawthorn trees,

Above my love and me,

And they will reach up to the sky Intertwined

be …’

She was singing not to death … but to hope. Hope that after death love might still survive, but hope none the same.

‘… And the hawthorn flower will bloom

where lie,

My fair-haired boy and me.’

The boy came to her, held her arms, looked deep into her eyes. ‘Thank you, Mrs Lavelle – Mother! Everything will be all right now – you’ll see!’

She didn’t know how to reply to him. Just squeezed his arms … let him go slowly, a certain sadness creeping over her. Maybe it was the song.

Then the Tennessee fiddle player called for a ‘last fling of dancing’ – ‘I Buried My Wife and Danced on Top of Her’.

Ellen was glad to be shaken out of her thoughts and as well didn’t want to send the men to sleep, morose about tomorrow. Though, even jigs and reels sometimes didn’t prevent that. She remembered Stephen Joyce wondering to her once about ‘how the Irish could be both happy and sad – at the same time!’

She entered joyfully into the spirit of the dance, lilting the tune, swinging and high-steppin’ it with her boys; Hercules O’Brien roaring at the top of his voice, reminding them all to ‘Dance, dance, dance all you can, Tomorrow you’ll be just half-a-man!’

Then a new sound – the stentorian voice of Dr Sawyer cutting through the din. ‘Stop it! Stop it at once!’

He looked the length of the hospital at them, withering them with his gaze, reducing them back to what they previously had been – men of rank, diseased and disabled.

‘It’s madness, sheer irresponsible madness! Sister,… you are in charge here?’

Louisa stepped forward: – ‘Yes, Doctor.’

‘These men, half of them at death’s door and look at them – lungeing about like lunatics … limbless lunatics.’

The men huddled back at his onslaught.

‘Feckless nuns and jiggers of whiskey – against my better judgement from the start. This won’t go unanswered!’ And he turned and marched out, killing all joy.

‘You won’t best us!’ Hercules O’Brien shouted after the retreating figure. ‘Even if it’s our lastest Paddy’s Night … it was the bestest.’ Then he turned, went down to where Ol’ one-armed Alabarmy now stood, all crumpled and defeated.

All watched as Hercules O’Brien bowed to his foe.

‘Thank you, sir, you’re a gallant soldier.’

Then Ellen, Louisa and Mary watched, the splendour rising in them, as each of the lame and the limbless, the Southron and the Northman, bowed to each other, offering gratitude for the frolics now finished and solicitude for whatever the morrow might bring.

In turn then the men thanked Ellen and the Sisters – especially Sister Mary for ‘The jiggers of whiskey and one helluva party for a nun!’

Those that could fight would want to be up and bandaged by five o’clock. That meant four for Ellen and the others. If they weren’t called on during the night and Ellen suspected they might well be. Dr Sawyer had been right … up to a point, and damaged limbs could only take so much. Still, they settled the men down as best they could and changed any dressings, oozing from the evening’s exertions.

And it was all worth it. The night’s fun was worth it.

The fiddling was furious, the band of fiddlers flaking it out. Ellen recognised them. There was Hercules O’Brien mummified for death. His head bandaged; blood plinking from his bow.

There too, was Ol’ Alabarmy thwacking his bow madly across his instrument. Where was his other hand? Grotesquely, the fiddle stuck out from Alabarmy’s neck, there being no other visible form of support. And Herr Heidelberg, atop a giant barrel. Like the others, he held a bow. To it was fixed a bayonet. When, each time, he drew his bow across the strings, it sliced a collop of flesh from his face. She cried out to him, but he seemed not to hear.

Ellen and the boy, Louisa’s boy, were in front of the fiddle band, dancing ‘The Cripples’ Waltz’ but the timing was wrong … all wrong. The fiddle band played one tune, they danced to a different one, the boy whispering loudly to her to ‘Listen! Listen, Mother! D’you hear it – in the floor – the skulls?’

She didn’t know what he was talking about. But he persisted at her to ‘Listen!’ Again calling her ‘Mother.’

Then, at last she could hear it. The amplified sound of their feet exploding on the floor, driving up her legs, shivering into her body.

‘It’s the skulls!’ he whispered, with a mad glee that she had at last understood him. ‘That’s what gives it the sound – the skulls, goat skulls and sheep skulls and … and … listen to the walls!’ he then demanded, pulling her close to the wall, pushing her face against it until she could feel the wild music entering the hollowed-out eyes and ears … and the slit of the nose. Coming back louder than when it went in. They did it in Ireland he told her. Buried the skulls of dead animals in the floors and the walls. To catch the sound of the wicked reels and the even wilder women who splanked the floor to them.

The music came thick and furious. She recognised the tunes – ‘I Buried My Wife and Danced on Top of Her’, then ‘Pull the Knife and Stick It’.

The only dancers were the boy and her. She wanted to ask him about Louisa … about … but he kept telling her to ‘listen!’, like she was the child. She obeyed him, the skull sound all the time rapping out its rhythm like a great rattling gun. It got louder and louder, until frightened, she looked at the floor. There, reaching up from beneath, were hands without arms and arms without hands.

If she could only dance fast enough, she could avoid them. Keep one step ahead. She shouted at the Cripple Band to play faster. But the faster they played the more Herr Heidelberg’s bayonet slashed his face, the more the bow of Hercules O’Brien splinked blood onto his face, his tunic, and his instrument. Ol’ Alabarmy smiled dreamily through it all.

The boy seemed not to notice, not to see. Only to hear. ‘Isn’t it beautiful?’

She tried to fight him off – make him see. He must be blind, crippled as the rest of them. Now, he caught her roughly by the shoulder, again trying to face her towards the wall.

‘No!’ she shouted, trying to get away from him. Trying to keep dancing, keep ahead of the jiggling hands.

‘No! No!’ she shouted, more vehemently, trying to wrest her body free.

‘It’s time, Mother – four o’clock!’ Mary said, gently but firmly shaking her shoulder.