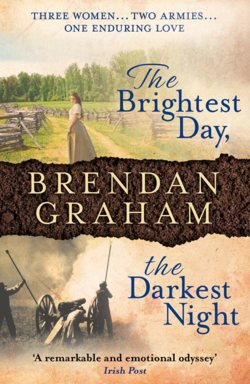

Читать книгу The Brightest Day, The Darkest Night - Brendan Graham - Страница 15

EIGHT

ОглавлениеUnion Army Military Field Hospital, Virginia, 1862

Manual of Military Surgery for the Surgeons of the Confederate States Army

‘… the rule in military surgery is absolute, viz: that the amputating knife should immediately follow the condemnation of the limb. These are operations of the battlefield and should be performed at the field infirmary. When this golden opportunity, before reaction, is lost, it can never be compensated for.’

Wearing Dr Thackeray’s spectacles, Ellen read carefully the surgery manual. The spectacles had been such a boon to her, not that she could overdo it, but a world previously closed had now again been opened.

She paused, thinking about her eyes before continuing. They had troubled her less than expected. Not that they were perfect. At times she found herself looking slightly to the right of people, as if they had imperceptibly shifted under her gaze.

Reading was problematic. She laughed to Mary about, ‘How childlike my reading skills have become.’ But, in general, she found the condition of her eyes to be of little hindrance to her work.

Dr Sawyer had been marvellous, procuring a continuation of Dr Thackeray’s soothing balm. He had also today located for her a pair of more recently developed shaded spectacles, an improvement on those given her in Boston.

‘Developed alongside those new-fangled rifle sights,’ he had told Ellen. He, Dr Shubael Sawyer, rather brusque of manner but an efficient practitioner of his profession, was the operating surgeon in the field hospital in which she, Louisa and Mary now found themselves.

‘Maybe this war, after all, will bring some benefit to humanity … though such benefits will weigh poorly enough when the balances are writ,’ Dr Sawyer had added.

These she now substituted for Dr Thackeray’s spectacles and continued with reading the manual …

‘Amputate with as little delay as possible after the receipt of the injury. In army practice, attempts to save a limb, which might be perfectly successful in civil life, cannot be made. Especially in the case of compound gunshot fractures of the thigh, bullet wounds of the knee joint and similar injuries to the leg, in which, at first sight, amputation may not seem necessary. Under such circumstances attempts to preserve the limb will be followed by extreme local and constitutional disturbance. Conservative surgery is here in error; in order to save life, the limb must be sacrificed.’

So there it was, in black and white. The saw saved lives.

In the time she had been here, Ellen had lain hands on everything she could read on medical practise. Not that there was much available. Good fortune had brought her current reading, The Confederate Manual of Surgery. A prize of war captured from the enemy. But there was a shortage of nurses for the many hospitals the war had occasioned. They had received some training from a Sister of Mercy who had then been moved to some duty elsewhere. She, like Mary and Louise, had had to learn quickly. It had been trial and error, mistakes made, while assisting at the regular stream of operations and mostly amputations.

‘Hips … I don’t like hips,’ Dr Sawyer said plainly to her later that afternoon. ‘Too near the trunk. We lose ninety per cent if we have to take the leg from the hip joint … and one hundred per cent if we don’t!’ It was Ellen’s first hip joint operation.

Three aides were required for such an operation. ‘Fetch the Sisters,’ Dr Sawyer ordered her. ‘The sight of blood holds no terrors for them.’

The soldier, a wan looking boy from Rhode Island, with freckled face and red hair had lost a lot of blood.

‘Pray, ladies,’ he said, when Mary and Louisa arrived, ‘that I’ll be one of the ten per cents! I ain’t seen much of life.’

They laid him out on the only available operating table – a diseased-looking church pew.

‘I hope it’s a good Catholic pew and not a Protestant one, Sister!’ the young soldier said to Mary, putting a brave face on it. She held his hand, making the Act of Contrition with him, something of which Mary was aware Dr Sawyer did not approve.

‘O my God, I am heartily sorry for having offended Thee … and I detest my sins … firmly resolve never more to offend … but to amend my life …’

When he had repeated the words firmly resolving to ‘sin no more’ Mary administered the chloroform by means of a dampened napkin. This she held cone-shaped over his mouth and nose, telling him to ‘inhale deeply’, ensuring that he also had an adequate supply of natural air while inhaling. Soon the young Rhode Islander was in a surgical sleep, though still exhibiting the ‘state of excitement’ they had come to expect in the early stages after administration of the anaesthetic.

‘Remove his uniform, Sister,’ Dr Sawyer ordered Louisa. Deftly, while Ellen restrained him, Louisa opened the top of the soldier’s tunic and with Mary’s help slipped it off. Then, she rolled up his flannel shirt to the chest. Next, Louisa unbuttoned his trousers, the left side peppered with shot and clotted with blood. She at one leg, Mary at the other, together pulled the trousers from him. The doctor waited while they addressed the matter of the boy’s undergarment. He noted that not once did either woman flinch from the indelicacy of her task.

‘Mrs Lavelle!’ was all Dr Sawyer then said.

Ellen had assisted him previously on other operations and knew what was required. Quickly, she swabbed away the matted blood from the boy’s shattered hip. She looked at the doctor for affirmation that his point of incision was now clearly visible. He nodded. Then Ellen slipped one of her hands under the boy’s buttock, the other one meeting it from the top. Her hands, stretched to their limit formed a human tourniquet. Her job, to stop all blood to the site of amputation. Thumbs meeting she pressed hard, clamping the thigh, praying to God for the strength to maintain the pressure. If everything went to plan it would be over in less than three minutes. Dr Sawyer was quick. Time being of the essence.

She closed her eyes thinking of nothing else but the exertion of her hands.

The technique the doctor would use was the oval method. This, though similar to the older, circular technique, lent itself better to amputation through the joint capsule – the cut made higher on one side of the limb than the other. Using the ebony-handled Lister amputation knife handed him by Louisa, Dr Sawyer made the incision in the Rhode Islander’s skin. Mary then retracted the skin to allow the muscle tissue to be cut. ‘An ample flap, Sister!’ the surgeon warned. An ‘ample flap’ of skin was critical after the operation, for recovering the heads of bones exposed by the saw.

‘Raspatory!’ Shubael Sawyer demanded the bone-scraper, which Louisa was about to hand him. The smashed bone, now exposed, was dissected back with this implement.

Meanwhile, Mary, checking the boy’s pulse found it had sunk too low and in a sure voice asked, ‘Ammonia?’ When the doctor nodded, she applied a quick whiff of liquor of ammonia to revive the patient. Louisa next handed the large rectangular-shaped Capital Saw to the fast-working surgeon.

Ellen turned her head away as the saw bit into the boy’s hip socket and then hacked its way through the bone.

‘Pressure, Mrs Lavelle! Pressure!’ Dr Sawyer rasped at Ellen, and she willed her thumbs and fingers to clamp even tighter around the boy’s thigh.

It was over in no time. With the tenaculum, Dr Sawyer then winkled out the main arteries, the blood dropletting from them. Ellen held on for dear life to stem its flow. Working quickly the doctor next ligated the blood vessels with surgical thread. In advance of the operation Ellen had already wound this silken thread around the tenaculum. Now Dr Sawyer slipped it from over the instrument onto each severed vessel, and tied. Only at his command to ‘release!’ did Ellen slowly uncoil her hands from what was now the remaining stump of the young soldier’s hip.

All eyes focused on the ligations – the full flow of blood now released against them. They held fast, no oozing apparent. Next was required the Gnawing Forceps to grind down the stump of bone to an acceptable smoothness. The flaps of skin, which Mary had previously retracted, she now folded back over what was left of the boy’s hip. Using curved suture needles, Shubael Sawyer knitted together the skin with surgical thread, but loosely, to allow for post-operative drainage of the severed thigh. Louisa then fanned the patient to purge his lungs of the chloroform and administered another whiff of liquor of ammonia, neither of which served to resuscitate him.

‘Brass monkey,’ the doctor ordered. Louisa never raised her eyes, immediately understanding the abbreviated form of the expression the men used to describe weather – ‘So cold it would freeze the balls off a brass monkey!’ She uncorked the chloroform and sprinkled it on the young man’s scrotum. The immediate reaction of cold caused a stir in him but not sufficient to bring him to consciousness. Louisa then administered a further, more generous sprinkling. This time the Rhode Island Red bolted upright.

‘My balls – they’re frozen!’ he shouted in disbelief. Then, remembering those present, groggily apologised, ‘I’m sorry, ladies … Ma’am,’ and made to cover his indecency. His severed limb, now on the floor parallel to the pew on which he sat, seemed to trouble him less greatly than his exposed and frozen manhood.

Later they learned that the Rhode Island Red had succumbed to his injuries.

Became one of the ninety per cent failure rate for such operations. Didn’t make the ten per cent.