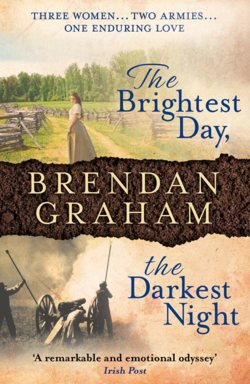

Читать книгу The Brightest Day, The Darkest Night - Brendan Graham - Страница 19

TWELVE

ОглавлениеMary watched Ellen move among the men. The transformation in her mother since first she and Louisa had found her was nothing short of miraculous. Ellen’s hair tied back from her face, accentuating her finely chiselled features, seemed to strip away the years. Modesty prevented Mary from ever using a looking glass but now, involuntarily, she put a hand to her face, fingering the high cheekbones, the generous span of mouth, the furrow between lips and nostrils. Upon her own face, Mary found replicated every feature of her mother’s. She smiled as she watched Ellen go about her duties with an enthusiasm that further belied her years. In her plain blue calico dress – its only adornment a neat white collar – Mary’s mother had a word for everybody.

‘God never closes one door but He opens another,’ Mary said to Louisa, marvelling how, after their banishment from the convent, the three of them had found such a fulfilment in their work here on the battlefields. Such an all-enveloping joy at being together again after all those years.

‘Her heart still longs for Patrick and Lavelle,’ Louisa answered. ‘She will not remain here forever, Mary.’

‘Oh, I know, Louisa …’ Mary answered, ‘but whatever the future holds, I will always hold dear these memories, these beautiful moments, of Mother bending to comfort a departing soul, writing out a letter to a loved one … of just being restored to us. I would happily depart this world with such images graven forever on my heart.’

Louisa, too, had witnessed the change in Ellen, the re-blooming; the coming of joy. All of which was a source of similar joy to Louisa herself!

She could not love Ellen more. Their time together here had been restorative for each of them in its own way. It was a privilege to serve those fallen in battle, to bind up their wounds – a rich and rewarding privilege. So, that when word had come down, from the Surgeon-General’s office, through Dr Sawyer, asking her to accept the role of matron, Louisa had wholeheartedly accepted.

She now spoke to her sister. ‘Well, before you take your leave of us, Mary, we have a St Patrick’s Day celebration to organise!’

Not that St Patrick’s Day was anywhere near in the offing. Nor that this mattered to those Irish currently under the care of the Sisters. Now, in the midsummer of 1862, the Irish had decided that ‘this little skirmish’ here in America should not prevent them from celebrating the national saint’s feast day … even if some three months after the declared date of March 17.

‘To show these foreigners, North and South, how to have fun,’ Hercules O’Brien put forward to Louisa. ‘We had a great St Pat’s … beggin’ your pardon, Sister, St Patrick’s Day, during winter camp when there was no fighting … but that was only among ourselves … and sure it’s now we need a diversion.’

After repeated ‘spontaneous’ entreaties from a number of the men – carefully orchestrated by O’Brien – Louisa had acquiesced. As matron, she warned that any celebration would have to be both ‘orderly and circumspect’. She received every assurance it would … ‘be as quiet as a dormouse dancing’. Somehow, Louisa felt remarkably unassured by this assurance, as Jared Prudhomme’s blue eyes beckoned her to him, for the third time that day.

Jared Prudhomme, proud to be from Baton Rouge, Louisiana, was ‘the man side of seventeen’, he told Louisa, when three weeks prior, he first came to them. He was tall, possessed of piercing blue eyes and with a beauty of countenance not normally bestowed on mortals. That he was dishevelled from battle, his blond hair unkempt about his face, did not in any sense diminish from his striking appearance. It was, Louisa had decided, because of some inner light of character which shone from the boy, and which was unquenchable.

She went to him. As on the two previous occasions today, she would be polite, not overstay with him, as she had when first he fell under her care. Then, though his shoulder wound had not been serious, due to a delay in getting him to hospital, he had lost a copious amount of blood. She had nursed him back, dressed his shoulder. One day, while leaning over him, their faces close, he had said, ‘You have the scent of the South on you … it reminds me of so much!’ She hadn’t answered him and then he was apologetic. ‘Did I embarrass you – I know you are not as other ladies?’ She had raised her head, looked at him, smiled. He had no guile. ‘Thank you,’ she had said and left it at that.

Then, one morning, she had arisen, found herself rushing her prayers. At first, she couldn’t quite fathom it but something about it bothered her. When she had reached his bedside, he had greeted her with his usual smile and she felt bathed in the light of his company. Leaving him, she realised that her earlier undue haste at prayers was not just to do her rounds but to get to him. When next she tended him, she was conscious of this feeling, her fingers betraying her as she peeled back the dressing from his bare shoulder.

‘I am unsettling you,’ he said in his quiet, direct way, ‘and I would rather fall to the enemy than cause any such emotion in you.’

This had discomfited her further.

‘Yes!’ she said, continuing her work. ‘It is an uncommon feeling …’ She paused, her words landing soft against his skin, her breath moistening the broken tissue.

Now, today, as she went to him, a faint tremor of apprehension came over her.

‘I wanted to ask you before everybody else … and maybe I am already too late,’ he began. ‘Would you dance with me tonight – for St Patrick?’ he added in quickly, upon seeing the look come over her face. ‘It is my last night, before going out again … and I would go more lightly having danced with you,’ he pleaded.

She looked at him, mended now, his face aglow at her. She had intended giving him a further talk about how ‘All must be included in a Sister’s love’ or that ‘Sisters, in spirit and in substance, must be faithful to their vows as a needle to the Pole.’

He looked so young, so fragile, his blue eyes entreating her, that she had not the heart. Before she had thought it out any further she had said ‘yes!’, the words of Sister Lazarus pounding in her brain … ‘Impetuosity, Sister, will be your undoing. You must guard against it!’

The rest of that day Louisa allowed no excuse to bring her within the company of Jared Prudhomme.

Somewhere, somehow, Mary, in her own quiet way, had managed to forage a few gills of whiskey, some for everyone in the hospital. Not that she was in favour of the pleasures – or dangers – of ‘the bewitching cup’, herself.

‘Blessings on ye, Sister – your mother never reared a jibber,’ or some other such well-meant phrase, greeted the dispensation of the whiskey. Some had to be helped drink it. One soldier, half his neck torn away, tried to gather up the precious fluid in his hands each time it seeped from his throat. Being a fruitless endeavour, he finally abandoned it. Instead cupping the amber-coloured liquid directly back into the gaping hole itself.

‘A shortcut, ma’am,’ he gasped to Mary, the rawness of the whiskey snatching the breath from him.

Another dashed it on the stump of his leg to ‘kill the hurtin’.’

Overall, Sister Mary’s whiskey produced a tizzy of excitement among the men. Americans, North and South toasted ‘the Irish, on whichever side they fight’, while the Irish toasted themselves, St Patrick, and the ‘good Sisters’, in that order.

The day, aided by the whiskey, invoked a kind of nostalgia in all of them. Some dreamed of the South – magnolia-scented days, fair ladies and the Mississippi. Some dreamed of the green lushness of the Shenandoah Valley. Others again sailed to further waters and valleys – the Rhine, the Severn, the Lowlands of Holland.

The Irish dreamed only of Ireland.

Ellen thought of the Reek, St Patrick’s holy mountain.

‘Do you remember how once we climbed it to look over the sea for a ship to America?’ she asked Louisa and Mary.

They both nodded.

‘I was afraid you wouldn’t take me with you,’ Louisa said. ‘That after finding me, you would leave me. I prayed so hard to St Patrick.’

Ellen remembered too when she had returned to Ireland to collect them. Her money had been running low, with staying in Westport, waiting for passage to America. She had herself, Patrick and Mary to look out for first. Rescuing the girl from the side of the road had been an impulsive charity, one she had already been beginning to regret. But a ship had come before she was forced to take a decision about ‘the silent girl’, before they had named her ‘Louisa’.

‘Little did any of us then know what lay before us in this far-off land,’ Mary reflected.

‘We’re still split apart from each other here,’ her mother answered, thinking of those not present. Only this time it wasn’t the famine, or ‘the curse of emigration’, or some other external force. This time it had been her own fault; her own fallibility that had scattered them. She was fortunate to have found again Mary and Louisa, or rather to have been found by them. But always her thoughts went to Patrick and Lavelle.

Of them there was no sign.

She knew they were out there somewhere, either with the Union Army of the Potomac, or with the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia.

A chill crossed her. They would have seen combat by now. She looked around the room. She always looked when a new consignment – the flotsam and jetsam of each fresh battle – arrived. Each time she looked, dread was in her eyes and in the back of her throat, and in the petrified pit that was her stomach. Now, as her gaze took in the men about her – a torn-out throat, a hole through a nose, like a third, sunken eye, a lifeless sleeve or trouser leg – she would have been happy to see them there. At least know that they were alive.

In her care.

‘I know what you’re thinking, Mother.’ It was Mary. ‘Trust in the Lord!’

‘Oh, I do, Mary! Believe me, I do – but sometimes I just wish I could help Him a bit more!’

‘You are … by helping those whom He has put in your way to help,’ Mary answered.

‘Mrs Lavelle!’ – it was Dr Sawyer.

The mound of amputated limbs had grown so high outside the ‘saw-mill’ window that they now tumbled from the top and were strewn on the ground like disarrayed matchsticks. The doctor wanted some order – these scattered limbs retrieved and a second mound started beside the first one.

Three months prior she would have fallen faint at the prospect. Now, she never flinched, nor did Mary and Louisa, who came to help her.

Ellen began to gather the legs and the arms. She tried to avoid picking them up by the hand or the foot. Did not want to touch the fingers or toes, have that intimacy. This proved impossible.

At times there was only the bare, half-hand, or the foot, where the surgeon had tried to save most of the arm or leg.

Then she began to recognise them. Couldn’t help but remember the stout arm of Jeremiah Finnegan, or the worm-infested leg of that sweet young Iowa boy, now with gangrene set in. Somehow, it wasn’t so bad if the rest of the body was alive, back inside the hospital. From some of the limbs, fresh blood still oozed so that they were warm and living to the touch.

It wasn’t right. They shouldn’t be allowed to accumulate here like heapfuls of strange fruit, burning in the sun until the blowflies and maggots came. Those over which the maggots already crawled, she picked up with her apron, then shook off what worms remained on her, once she had deposited the putrid limb. Other limbs had corroded to the bone, caked by the sun, stripped clean by flesh-eating things.

To distract her mind she recited the Breastplate of St Patrick:

‘Christ with me,

Christ before me,

Christ behind me,

Christ within me,

Christ on my right hand,

Christ on my left hand,

Christ all around me,

Christ in the heart of all who think of me,

Christ in the mouth of all who speak of me,

Christ in every eye who looks at me,

Christ in every ear who listens to me.’

Even the words of the prayer seemed to take on an incongruity, far removed from their intended bidding.

‘Christ on my right foot,’ she prayed while handling a foot, pierced through like a stigmata. She remembered the poor wretch who had, in a state of fear, pulled the trigger of his rifle before raising it to the enemy and shot himself.

‘Christ on my left foot.’ She had it all out of kilter. But did it matter? She cast the stigmatic foot onto the mound, watched it slide down again in some crucified dance.

‘Christ with me,’ she intoned, invoking again the protection of the saint’s breastplate.

And the stench, the yellow dripping stench: powerful, unavoidable, permeating her clothes, her pores, the follicles of her hair. She thought she would drown in its noisome pool, it oozing over her whole body, closing out air and decency.

She redoubled her prayer but the drenching slime slid into her mouth, over her tongue and down her throat like the melt of Hell.

When they had finished she went straight to Dr Sawyer, gave him her mind about how ‘the great Abraham Lincoln couldn’t even run a decent abattoir, let alone this war or this country!’

That evening the regular cries for relief and ‘Sister! Oh Sister!’ were broken by a new sound. That of someone scratching out a tune on an asthmatic fiddle. Where the instrument came from nobody knew or, if they did, would not reveal.

Soon the fiddler, a Donny McLeod late of the Scottish Highlands, via East Tennessee, was madly flaking out the old mountain reels. For Ellen, the tunes recalled better days of sure-footed dancers, the men hob-nailing it out, striking splanks from the floor, while slender-waisted girls swung from their arms. Now, the magic of the wild fiddle music seemed to banish away forever the misfortunes of the waiting war.

It was Hercules O’Brien who started it.

Up he rose, arm in a sling – which he immediately cast off.

‘Head bandaged like a Turk, with only the ears out,’ as he described himself, he grabbed hold of the remaining arm of a grizzled old veteran.

‘C’mon, Alabarmy – let’s see if you can dance better than you fight!’ the little man challenged.

‘Well, I’ll be darned, O’Brien, if any o’ that Irish nigger-dancin’ will best ol’ Alabarmy,’ the Southron answered back.

And the two faced each other in the middle of the floor, Hercules O’Brien lashing it out heel to toe for all he was worth.

‘You’s sweatin’ like a hawg,’ Alabarmy goaded as the blood seeped out through his partner’s bandaged head. ‘Like a stuck hawg!’

A great roar of laughter arose at this goading of the Irishman.

Not to be outdone, Hercules O’Brien shouted back above the din, ‘And if you’d lost a leg ’stead of an arm, you’d be a better dancer,’ which raised another bout of laughter. Then the Irishman crooked his own good arm in Alabarmy’s one arm and swung him … and swung him in a dizzy circle with such a wicked delight. Until they all thought Alabarmy would leave this earth, courtesy of the buck-leppin’ O’Brien.

Next, another was up and then another, curtseying to prospective partners, the ‘ladies’ donning a strip of white bandage on whatever arm or leg they had left to distinguish themselves from the men.

‘Could I have the pleasure, Jennie Reb?’ Or ‘C’mon, Yankee, show us your nigger-jiggin’!’

Ellen stood watching them, the music reeling away the years. Back to the Maamtrasna crossroads, high above the two lakes – Lough Nafooey and Lough Mask. Them gathering in from every one of the four roads, the high bright moon lighting the way. Like souls summoned from sleep the dancers came, filtering out of the night to the gathering. There, under the moon and the great bejewelled sky they would merge out of shadow – a glance, a half-smile, then hand within hand, arm around waist, breath to breath. Then bodies in remembered rhythm would weave their spell, and they would rise above the ground, be lifted; the diamond sky now at their feet – a blanket of stars beneath them.

The priests were right – the devil was in the dancing, in the wicked reels; the way you danced out of your skin, out of yourself. ‘Going before themselves,’ the old women called it. Leaving sense and the imprisoned self behind. Being lost to the dance.

Remembering wasn’t good, Ellen reminded herself. A life could be lost to it … wasted, looking backwards. Looking forwards was as bad. She was of late looking too much backwards, and looking forwards, wondering where, if ever, she would find Lavelle and Patrick. Trapped between the future and the past, no control over either. Helplessly suspended in the now.

Ellen took in the scene in front of her. Was that all that mattered? All there was? The now of these broken men, momentarily lifted above the brutal earth to dance among the stars?

Across the room she saw Foots O’Reilly in conversation with Mary. Then she watched Mary bend, her arms encircling the man’s back, lifting him into a sitting position. He was from Cavan ‘and a mighty dancer,’ he had told Ellen, ‘could trip over the water of Lough Sheelin without dampening me toes.’ Hence, the nickname ‘Foots’. Then a Southern shell had ripped one dancing leg from under him.

‘That won’t hold Foots O’Reilly back none,’ he swore. Tomorrow he would undergo the surgeon’s saw to save the second leg, gangrened to the knee.

‘I could dance with the one, ma’am, but I can’t dance with the none. Now I’ll lose me name as well as me pegs. “Foots” with no foot at all to put under me.’ He had cried in her arms then.

Ellen watched Mary hoist the one-legged dancer, so that he half stood, half leaned against her, arms clasped to her, head draped over her shoulders. She dragged him out to the dancing square. The others witnessing it stopped, even the fiddle boy. Then Mary whispered into his ear, ‘Come on now, Mr O’Reilly. Dance with me … you show them!’

And she manoeuvred him slowly around in the silence, his gangrenous leg trailing behind them. Then again and again they turned, in grotesque pirouette, she in her white nun’s ballgown, he the mighty dancer, until Mary could support his dead weight no longer.

‘Thank you, Mr O’Reilly … Foots,’ Mary said to him. ‘I shall always remember this dance …’ and she sat him gently down again.

Then, all those who could were once more ‘footin’ it’: the wounded and the wasted, the stumped and the stunted. All flailed and flopped and picked themselves up again as the fiddler played his relentless reel. Then, suddenly, he changed into waltz-time.

‘I thought he’d kill the lot of them …’ Ellen said to Mary who had come beside her, ‘… but isn’t it wonderful to see?’

Mary smiled back at her.

As the young Tennessean, bow astride his fiddle, led them into the waltz, they watched Hercules O’Brien prop up Alabarmy in front of him, placing the Southerner’s shelled-out sleeve over his shoulder. Twins from Arkansas – a crutch apiece – hobbled around in a kind of teetering dance, Ellen ready to catch whichever one of them, who any minute must fall.

Then, someone bowing to Ellen … a deep bow. It was Herr Heidelberg, the Dutchman, as the men called the German soldier from the town of the same name. Like all who had come newly to America, Germans as well as the Irish, Poles and a host of other nations had joined in the fray to fight for their ‘new country’ – the North in Herr Heidelberg’s case.

‘I better likes dance mit de Frauen den de Herren,’ he said shyly.

What Ellen could see of Herr Heidelberg’s face was pink with both excitement and embarrassment. The German was the object of much ridicule from the rest of the men due to his manner of speaking, and now could risk further ridicule.

Ellen curtseyed to him.

‘Delighted, Herr Heidelberg!’ she replied.

It was the only name by which she knew him … and though denied his real name, the association with his hometown had always seemed to please him.

Herr Heidelberg swept her around like a Viennese princess, her dress spattered with the earlier work of the day, flouncing about her. The men made space for them, Ellen and her waltz king with half a face, clapping them on to twirl upon twirl, him counting to her under his breath.

‘Ein, zwei, drei, ein, zwei, drei.’ His bulk making her move like a turntable doll, just to keep pace with him. And all the while the young fiddler discoursing sweet music from his violin.

When they had finished, the others all clapped and cheered – and cheered again, more loudly; those who could not clap, clanking their crutches. He turned to her, flushed with delight.

‘Danke schön! Danke schön … I have not so very good time before in America,’ and she saw the tears form and spill down his bandaged cheek.

‘Thank you, Herr Heidelberg. You’re a brave dancer.’

He beamed at her and self-consciously retired away from her to the rear of the ward.

Finding herself beside the young fiddler Ellen enquired of him the tune. ‘It has no name … I picked it up from folk in the foothills.’ He smiled at her. ‘I could call it “The North and South Waltz”.’

‘More like “The Cripples’ Waltz”, ma’am, beggin’ your pardon,’ Hercules O’Brien chipped in, ‘’cos that’s what it was!’

‘If you was a gentleman, Sergeant O’Brien,’ the fiddler remonstrated, ‘you’d name it for the lady …“Mrs Lavelle’s”, or, with permission, ma’am, “Ellen’s Waltz”.’

‘Waltzes can be trouble …’ she said, remembering Stephen Joyce, and something about ‘the carnal pleasures of the waltz’.

‘I am honoured but perhaps there is a young lady in East Tennessee who more greatly deserves the honour,’ she said … and he struck up another waltz as if in answer.

All of a foam after her own decidedly non-carnal waltz with Herr Heidelberg, Ellen went to the open doorway for some cooling air. She stood there watching the sky, listening to the music, thinking of those whom she most dearly missed. The sky, the everlasting sky. Lavelle out there under it. Dead or alive. Maybe watching that same sky, thinking of her. An old poem-prayer – pagan or Christian, she didn’t know – formed on her lips. She had learned it at her father’s knee. All those nights of wonder long ago, under the sheltering stars. High on the Maamtrasna hill, above the Mask and Lough Nafooey. Above Finny’s singing river. Above the world.

‘I am the sky above Maamtrasna,

I am the deep pool of Lough Nafooey;

I am the song of the Finny river,

I am the silent Mask.

I am the low sound of cattle

And the bleating snipe;

I am the deer’s cry

And the cricket’s dance.

In the lover’s eye, am I;

In the beating heart;

I am the unlatched door;

I am the comforting breath.

Now and before, after and evermore,

I am the waiting shore.’

‘The waiting shore,’ she repeated, the great sky listening. ‘I am the waiting shore.’

Music, dancing, always seemed to start her thinking. Too much of it was bad. Thinking led to feelings. High, lonesome feelings like the fiddle-sound behind her. Still, these days she didn’t much give into herself. Just kept working with a kind of blind faith. That one day she’d find them, or they’d find her. Looking back on life was as bad as looking back on Ireland. She was done with all that, was now facing the new day – whatever that might bring … to wherever it might lead her. Like here … a pale ‘St Patrick’s night’ in Virginia – … Maryland … Carolina. She’d never thought of States as feminine. Then again, men were always naming a thing for their women, as if to protect – or to own – it. Louisiana … Georgia … the Southern States seemed to have the best of the gender divide. Louisiana – Louisa’s Land. Ellen thought of her adopted daughter.

Louise, in many respects, was more like herself than Mary was. If not in looks, then certainly in temperament. Ellen smiled. Louise had some inherent waywardness. Needed always to be holding herself in check; dampening down her natural high spirits. Her passion for this life sometimes out-balancing her preparation for the next.

Ellen looked back through the door, to catch a glimpse of Louisa. There she was, gaily dancing with that young Southern boy Jared Prudhomme. Ellen had noticed them talking together. She would speak to Louisa about it.

The one thing, Ellen knew, which held the Sisters high in the respect and affections of the men, was that they, unlike the lay nurses, divided their care equally among all the men. To move from this understanding would undermine the position of the Sisterhood – and re-instate all the barriers and prejudices they had worked so hard to remove. Louisa’s vocation, Ellen knew, was more difficult than Mary’s. Louisa would always be torn between the things of the world and her higher calling. More passionate, more reckless than Mary, Louisa went headlong at life. Not always a good thing. In moments left Louisa unguarded against herself. Much as Ellen herself had been.

Ellen looked again. Mary too was caught up with the celebrations. But it was different. This Earth, with all its hollow baubles, was merely a waiting place for Mary. Until she was borne away by an angel band to eternal glory. Even in that, Mary had an unsullied purity of thought. She did not seek everlasting life, as a thing in itself. With her, it was ever the higher ideal – to see His face, to continue her worship of Him in Heaven as she had on Earth. Mary was fallible humanity at its most beautiful. Mary was a saint.

The sound of a galloping horse startled Ellen. Some news of a battle? Surrender? Peace?

Her heart leaped at the thought.

The horse, pale against the rising moon had no rider. It galloped by her, so close she could smell the thick odour of its lathering skin. On it ran until she could hear its distant drumming but see it no more.

‘“Behold a pale horse, And his name that sat on him was Death; And Hell followed with him;” Revelations, Chapter Six, Verse eight,’ she said, after it.

She remembered the Hades horse in the woods – the memories it had evoked. Black horse, pale horse. It reminded her of something. Out there too champing for battle was the red horse of slaughter, the white horse of conquest. Four horses in all, ever present at the revelation of evil – the Apocalypse. She felt a tremor run over her body.

She walked out a piece into the night, following the sound of the retreating hooves, the horse bringing back her old dream. Lavelle, constant, loving Lavelle, true as the guiding moon. Out there somewhere beneath it. And Stephen, he, who had excited such a temporary madness in her, awaking every reckless passion. She lingered on thoughts of him, their times together, her skin alive with the remembering. Under what moon, what banner, was Stephen Joyce? She dared not think. She and Stephen Joyce could never meet again. She dismissed him from her mind, irritated by her lapse, thinking she long ago had.

When Ellen turned to come back, she saw two figures flit away from the din of the hospital into the glinting night and towards the woods. She hoped they would not arouse the interest of jittery-fingered pickets who lay at every pillar and post between them and the enemy. Especially, as he was a Southern boy.

She would need to speak to Louisa. Urgently.