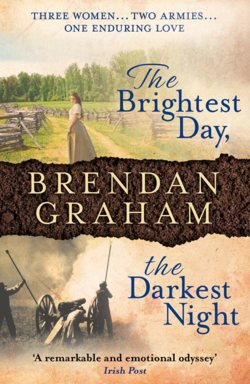

Читать книгу The Brightest Day, The Darkest Night - Brendan Graham - Страница 18

ELEVEN

Оглавление‘Niggerology! That’s what’s causing all the trouble!’ Jeremiah Finnegan roared. ‘That’s why all of yous in here is bent and broken. Niggerology!’ he roared again.

Ellen ran down the room to where the man was lying, head back, face to the ceiling.

‘If I’m going to die, I’m going to die roarin’!’ he yelled, before she could reach him.

‘Jeremiah! Jeremiah!’ she said sternly. ‘Stop that! You’re not helping any by shouting your head off.’

She caught him by his remaining arm.

‘But it’s true, Miss Ellie – it’s true! Look at me – all I’m fit for is to be roarin’!’

‘I know, Jeremiah, I know,’ she said more gently, looking at the half-man on the ramshackle cot; over one eye, a wad of cotton wool to cover the blank hole where his eye had been. Taken clean by a minié ball. Then his arm and his leg with cannon fire, as he fell.

‘I have only my roarin’ so that people can know me. I can’t see. I can’t walk. I can’t hold a lady to dance with. I’m eternally bollixed!’ he said defiantly.

She couldn’t but help smile at the man’s description of himself. With his one good eye he caught her smile – and kept going. ‘But I can ring the rafters of Heaven and Hell! Damn their heathen eyes – the niggers – and those what supports them!’

What could she say to him? ‘But you’re not eternally damned and neither are those “niggers”, as you call them,’ she whispered, rubbing her palm along his remaining arm.

‘Ticket’ Finnegan – as they called him back home in the County Monaghan hinterland, always wanting to be off, get his ticket to America … to anywhere out of the humpbacked hills of Monaghan – calmed to her touch.

‘I’m not afraid of dying, Miss Ellie,’ he said, still remonstrating with her. ‘But I won’t die easy, whimperin’ me way out like those Rebs over there. I came into the world roarin’ and I’m goin’ out of it the same way!’

‘I’m sure you are,’ she answered.

He was a fine block of a man; had a good few years on most of the boys that both armies had gobbled up. Now, like all around him, he had been cut down in his prime. It was a shame, a crying shame.

‘Is there anyone you want me to write to?’ she asked.

‘Divil a one – bar the Divil himself – to say I’m comin’!’ he said. ‘Just sit a while and talk the old language to me!’

She looked around the room. Everywhere, a chaos of bodies. Most of them incomplete. Most needing care and comforting – before or after the surgeon’s saw.

Ticket Finnegan hadn’t long left, probably less than most.

‘All right!’ she decided, and began to talk to him of the old times and the old places.

‘Tír gan teangan, tír gan anam – A land without a language is a land without a soul,’ he whispered as she spoke to him in the ancient soul-language of the Gael.

How true it was, and she thought of the ‘niggers’, as Ticket – and most of the Irish – called them. Most too, like him, believed the black people had no souls, were just ‘heathens’. So what then, if the heathens were also slaves?

Demonisation and colonisation.

The same thinking had demonised and colonised the Irish. Depicted them as baboons in the London papers; blaming the Almighty for sending down a death-dealing famine on them. When all He had sent was a blight on the potatoes. It was the English who had sent the famine. Stood by. Did nothing. Let a million Irish die. But what harm in that? Sure weren’t the Irish peasants only heathens … had no souls, only half human, somewhere between a chimpanzee and Homo sapiens … the missing link? Now she saw those self-same Irish peasants here being blown to Kingdom Come for Uncle Sam and they couldn’t see that it was the same old story all over again. Slavery had taken the black people’s language, their customs and traditions, their music. It had taken their country away from them – this new one – as well as those previously stolen from them. Slavery had tried to take their souls. Ellen O’Malley hoped it hadn’t.

Now she talked to this half a man, in the voice previously reserved for her children – a kind of suantraí or lullaby-talk. ‘I ain’t never been baptised!’ he said, surprising her. When she said she would send for a priest, he glared at her. ‘I don’t want no priest mouthin’ that Latin gibberish over me!’ Then his look softened. ‘Would you do it for me, Miss Ellie – you’d be as good as any of them … you and the Sisters?’

She called Mary and Louisa to be witnesses, and fetched a tin-cupful of water. Then, his head in her arm, like a new-born, she sprinkled on it a drop of the water. Having no oils with which then to anoint him, she moistened her thumb against her mouth. With it she made the Sign of the Cross on his forehead, his ears, over his good eye and on his lips saying, ‘I baptize you in the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghos … There now, you’re done … ready for any road.’

He was soothed now. His pain must have been intense. A miracle he had survived at all. Better he hadn’t. He shook free his hand from hers, reached over to where his other hand would have been. Forgetting.

‘I still feel it there, Ellie, but sure it’s only the ghost of it … only the ghost of it! If only I could wrap it round a lady’s waist,’ he said wistfully.

She took his hand again. ‘Will you pray with me, Jeremiah?’ she asked, still in Irish.

‘Sure isn’t what we’re doin’ prayin’?’ he replied, the good eye darting wickedly at her.

And she supposed it was.

‘I can feel the Divil comin’ for me, even after you sprinklin’ the water on me,’ he said, gripping her hand more tightly. ‘He took the one half of me and now the wee bollix is comin’ for the other half!’

He raised up his head, as if to see. ‘G’way off to fuck, ye wee bollix ye!’ he roared, startling her and the whole ward into silence. They were all well used to death by now – in its many guises. The sudden rap, the last rattle of breath, the gentle going – and those who roared!

She said nothing, just gripped his hand.

He raised his head again. ‘Who made the world?’ he shouted at them all.

‘Gawd did,’ a Southern voice called back.

‘Who made America?’

‘Paddy did!’ the Irish roared back, as Jeremiah Finnegan handed in his ticket. Leaving both God’s world and Paddy’s America behind him.

She waited a few moments. Disengaged her hand, shuttered close the one mad eye on him.

‘He died roarin’, ma’am,’ a gangrened youth in the next cot said.

‘That he did, son! That he did!’ she said, to the frightened boy.