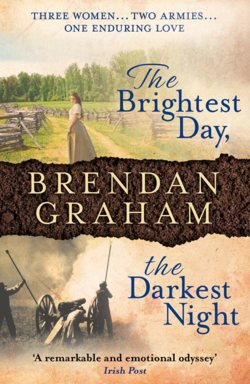

Читать книгу The Brightest Day, The Darkest Night - Brendan Graham - Страница 17

TEN

ОглавлениеThe hospital was one of many field hospitals dotted all over the countryside, wherever men might fall in battle. A once-schoolhouse, now it had rows of rough bunks lining each wall, an anteroom for amputations and an added-on storeroom for medical supplies and operating implements. A further room was used as a makeshift canteen – for those who could walk to it. A nearby cabin, abandoned to war, provided accommodation for Ellen, the two nuns, and occasionally for those who came temporarily to assist. Dr Sawyer had private accommodation some slight further distance away.

They could comfortably take one hundred patients – at times stretched to two hundred. Three nurses and a doctor were not sufficient … but it was all they had to make do with, most of the time.

Although officially a Union hospital for soldiers of the North, Mary and Louisa had impressed on Dr Sawyer that ‘all the fallen of whichever side, should fall under our care, if needed.’ It was not a philosophy to which the brusque doctor easily subscribed, even with Mary gently reminding him that, ‘if your own son were wounded near Confederate lines, you would wish some kind Sister to take him in – or a good Christian doctor, such as you, to save him.’

In the end he had little choice, the two nuns and Ellen gathering in whomsoever they found needing attention – Union Blue or Confederate Grey.

Regularly, Ellen enquired of those whom she tended from both North and South, of Patrick and Lavelle. But it was ever without success. Most were sympathetic, complimenting her on her son’s and husband’s valour in serving ‘the cause’ – whichever cause they considered it to be – and her own womanly duty to the wounded.

From a few, her enquiry evoked a different response – a gruff Georgian officer telling her, ‘Lady, chaos rules out there. Nobody knows nobody … no more. A quarter of my gallant lads were killed the first day, a quarter more the second. Moving men into battle is like shovelling fleas ’cross a farmyard – not half of them get there.’

She had begun to give up hope of ever seeing them again. This whole bloody business about ‘valour’ and ‘gallant lads’ was beginning to weary her. There seemed to be no end to the harvest of wounded and wasted who, day by day, were being shunted into the hospitals. Or the more deadly harvest … the hundreds and hundreds of young men being regularly flung two or three deep into earthen pits. A lonely thin board then scrawled with some illegible writing to mark their brief existence in this life. One such makeshift cross she had seen had stated only that: Here lyes 120 brave men who dyed for there contree. Not even the loved one’s name to comfort those who later would come searching for them.

‘Fleas across a farmyard.’ Word had come down that over a million men had begun the year massing for war. How in a million could she find but two – Patrick and Lavelle?

She never spoke to Mary or Louisa about her rapidly fading hopes. Nor did they enquire of her. She had asked Dr Sawyer and he had sought for her the list of the dead, wounded and missing from Union Headquarters. When it eventually came, he apologised for its incompleteness. ‘It changes hourly – they cannot write quickly enough to keep up with the dead.’

She raced through the names – O’Malley, Bartley; O’Malley, Thomas; O’Malley, John; O’Malley, Peter. She heaved a sigh of relief. No Patrick O’Malley. Nowhere either could she find the name Lavelle, making her think perhaps they had both sided with the South. It was some comfort, this not knowing – if only a crumb. Maybe Patrick had not become embroiled in this war madness after all? She prayed that if he had, he would be with Lavelle. Lavelle would shelter Patrick from harm, as if his own son, because he was hers.

Ellen thought she had witnessed everything in this demonic war but when Private Edward Long was smilingly delivered to her, she had to stop in disbelief.

‘How old are you?’ she asked the pint-sized patient.

‘Nine years, ma’am … but squarin’ up to ten!’ the private proudly replied.

‘Nine … years … of … age …?’ she drew out the words one by one. ‘Nine years of age?’

‘Yes, ma’am,’ the child confirmed, as if there should be any doubt in her mind.

‘Private Edward Long – Illinois – at your service, ma’am,’ he added, looking up at her.

‘Yes!’ she said, ‘but what are you doing here?’

‘For to get mended … again,’ he said, with all the innocence of childhood. ‘I got clipped by a minié ball.’

‘Where?’ she asked, and saw him hesitate. There was no obvious sign of injury on him.

He threw his eyes down to the ground.

‘I’m not saying, ma’am … but another one went in front of me and shot my drum.’

Then she understood. He had been grazed by a bullet on his buttocks and manfully wasn’t about to reveal that fact to any female. She resisted the urge to pick him up, cradle him in her arms.

‘All right, soldier!’ she said, ‘follow me – we’ve a special private place here for the brave musicians who lead our boys into battle.’

Off she set, him falling in behind her, trying to keep pace, swinging his arms up and down, all four foot six of him.

‘Where’s your mother?’ she asked, when she got him down to the end of the ward.

‘At home!’ he said, matter-of-factly.

‘Does she know where you are?’

‘Yes, ma’am,’ he answered, ‘she sure does. Me and all my six brothers joined up to fight. Four is dead now. Just me and Jess and Billy-Bob left.’

She looked at him. ‘You should go home, Edward,’ she said gently, thinking of his mother.

‘Oh, but I will, ma’am, when I git my furlough. I’ll be going home for a month.’

‘Why not stay there … with your mother?’ she persevered.

‘I couldn’t do that, ma’am,’ he said, his baby blue eyes fixed on hers, ‘until we whip the Rebs and send them home!’

She gave up. He was the youngest she had seen. Most of the American boys were about eighteen, the foreign soldiers older. Many, though, of the homegrown farm boys who enlisted were much younger.

‘A hundred thousand fifteen-year-olds’, Dr Sawyer had told her, ‘barely out of knee-britches and learning to kill! The fresh flower of manhood, thus brutalised by an old man’s war.’

She had seen them come in, stretchered and corpsed, some as young as twelve. But never before a nine-year-old.

She heard Louisa calling her, squeezed both his arms. ‘Wait here, soldier, you need the doctor to fix you up,’ she said, to spare his blushes.

‘What about my drum?’ he asked. ‘Can he fix my drum too?’

‘I’m sure he can,’ she smiled, and hurried to where Louisa and the commotion of some new arrivals beckoned.

The little fellow had grit, real Illinois grit. She doubted there was much the matter with him. They’d see to his bum and his drum. Send him home to his mother. Maybe this time she’d keep her little drummer boy at home in Illinois. If she could afford to feed another mouth as good as the army could.

Later, she sat deep into the night, keeping the last vigil with some frightened soul admitted earlier and for whom nothing could be done. Nights such as these were the darkest hours, when her God would seem to have deserted her and she would pray instead to Science. That it would deliver its yet most infernal machine, and in one hellish blow strike down the massing millions of men. Be so terrible a holocaust that it would stop everything. Then, the pitying cry of some farm boy, or some veteran’s curse, demanding her to be present, would draw her back from the abyss.

One such night she could bear it no longer. Stole away from her watch, went into the night. The land was flat here on the plains of Virginia – some rolling hills to break the monotony, the misty Blue Ridge Mountains to the west, behind them. It was a rich land, far better than what she had known in Ireland. No bare acre here but gentle farmlands where wheat could be harvested, peaches plucked, a pig or a rooster raised. Until they were commandeered for hungry marching bellies, by one side or the other … or stolen by marauding men, cut adrift from their regiments and the mainstream of battle. She walked to the copse of trees, now bathed in the glimmering moonlight of her adopted land. Sad for all that had been visited upon it. There in the sheltering trees she found a horse, black as Hades, gashed above the foreleg, watching over its fallen master. The man, a captain, was beyond repair. She prayed over him, went deeper into the twining trees, the horse hobbling behind her. Ahead some snuffling sounds.

Following the sounds, her eyes made out the low shapes of hogs, feeding on the ungathered dead.

She ran at them, shouting, the night-horse her ally. Grudgingly they gave ground, snorting and bellowing their way further into the undergrowth.

She scrambled onto the horse’s back, fearful they would return before she had raised help. The horse bore her bravely, terrible images assailing her mind. Images of the famished dead back in her own land, Ireland … ravenous pigs and dogs. Her own neighbours, every last hope of food gone; the cabin pulled down around them, so no one would witness their last indignity; the dog whose head she had cracked as it defended its food. Somehow, it all – the spectre of famine back again and the Hades horse – decided her. No longer would she remain a spectator, waiting. She would rise herself, go out and find Lavelle and Patrick.

And she would go South. When the time was right.