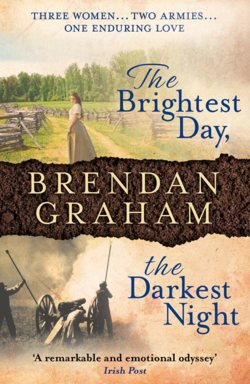

Читать книгу The Brightest Day, The Darkest Night - Brendan Graham - Страница 6

PROLOGUE

ОглавлениеHalf Moon Place, Boston, 1861

Ellen O’Malley opened her eyes.

Blinked.

Raised her head.

Waited, watching for the sky.

Soon the sun would come creeping into the corners of Half Moon Place. ‘Like a broom,’ she thought. Sweeping out the dark.

When the sun brushed along the narrow alleyway towards where she sat, she opened her throat, and began singing,

‘Praise to the Earth and creation,

Praise to the dance of the morning sun.’

She sat atop a mound of rubbish, raised from the ground and the sordid effluents that backwashed the alleyway. The mane of red hair that fell from her head to her waist, her only garment. The sailors who frequented the basement dram-houses of Half Moon Place, had rough-handled her, taken her clothes for sport. But no more.

Ellen hadn’t even resisted. Instead, offered prayers for their wayward souls, which hurried them off.

The glasses she missed more. The alley children had stolen them, fascinated by the purplish hue that helped her eyes. Years in the cordwaining mills of Massachusetts had taken their toll. But she was blessed more than most. Without them she could still see the sun and the stars and the moon. The shoe-stitching she could no longer do. She couldn’t blame Fogarty then, the landlord’s middleman, when eventually he put her out for falling behind with the rent. He wasn’t the worst; had stretched himself as far as one of his kind could.

Even in her current situation, any passer-by would have still considered Ellen O’Malley a striking woman. Firm of countenance, fine of forehead and with remarkable eyes. ‘Speckled emeralds,’ she had once been told, ‘like islands in a lake.’ She smiled at the memory. Tall, she sat unbowed by the circumstances in which she now found herself. Her fortieth year to Heaven behind her, a casual onlooker might have placed Ellen O’Malley at not yet having reached the meridian of life. A flattery from which, once, she would not have demurred.

She had only been out the few nights now and the New England Fall had not been harsh. Biddy Earley, whose voice Ellen heard at night, driving a hard bargain with the men of the sea would, in the daylight hours bring her a cup of buttermilk and a step of bread for dipping in it. Part-proceeds of the previous night. Likewise, Blind Mary, all day on her stoop in nodding talk with herself, would bring her a scrap of this or that, or the offer of a ‘gill of gin’. Then, nod her way homewards again, scattering with her stick the street urchins who taunted her.

Still with her song, Ellen reflected on her state. She was, at last, stripped of everything – a perfection of poverty. No possessions, no desires. Life … and death came and went along the passageways of Half Moon Place with such a frequent regularity that her situation attracted scant attention. Nor did she seek it.

‘Into Thy hands Lord, I commend my Spirit.’

Nothing remained within her own hands, everything in His.

It was a wonderful liberation to at last hand over her life. Not forever seeking to keep the reins tightly gripped on it. Death, when it came, would hold no fears for her. Death was re-unification with the One who created her.

She looked down at her nakedness, unashamed by it, her body now shriven of sin, aglow with the light of Heaven. She had been beautiful once, had fallen from grace, and now, was beautiful again; if less so physically, then spiritually at least.

She thought of her children: Mary, her natural daughter; Louisa, her adopted daughter; Patrick, her son and then, Lavelle, her second husband. How she had betrayed them; her self-exile from their lives; her atonement; and finally, now her redemption.

She had been right all those years ago. To unhinge herself from their lives after her affair … keep them free of scandal. Because of her the girls, postulants then, would likely have been driven from the Convent of St Mary Magdalen. With words like ‘the very reason the vow of purity is so highly prized among the Sisters is that, in its absence, it is humanity’s fatal flaw.’ Ellen considered this a moment … how very true in her own case.

And clothes? Clothes were the outer manifestation of the inner flaw – something with which to cover it up. Down all the centuries since paradise lost. Now, her paradise regained, she had no earthly need of them.

‘I am clothed …’ she sang in her song, ‘… the sun, the moon and the stars – finer raiment than ever fell from the hands of man.’

Then she prayed.

‘Jesus, Mary and Joseph, I give you my heart and my soul;

Jesus, Mary and Joseph, assist me in my last agony;

Jesus, Mary and Joseph, may I breathe forth my soul in peace with you. Amen.’

She followed with the Our Father – in the old tongue Ár n-Athair atá ar Neamh. Then finally, she raised to heaven the long-remembered prayers of childhood.

Afterwards she sang again. The songs she had sung to her own children – nonsensical, infant-dandling songs: aislingi, the beautiful sung vision-poems; and the suantraí, the ‘sleep-songs’ with which she once lullabyed them. Sang to the sun and the teetering tenements of Half Moon Place.