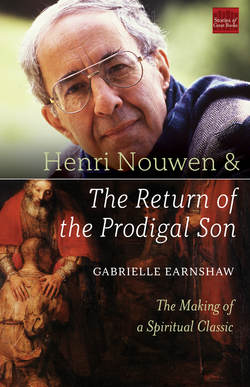

Читать книгу Henri Nouwen and The Return of the Prodigal Son - Gabrielle Earnshaw - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

“Work-to-Earn-Love” Ethos

ОглавлениеWhile acknowledging the complexity of the relationship and its ultimate unknowability, what we might consider is that Nouwen experienced a father with a “work-to-earn-love” ethos. From his father he learned that worldly success was a means to gaining love (see Home Tonight, 69–70). As a student and later as a young adult, Nouwen worked very hard to meet this criteria for love. He acquired multiple academic degrees; he published scores of books and was honored with awards and prestigious faculty appointments.

In this light, it is understandable why Rembrandt’s poster hit him so hard. He was exhausted from having to prove himself in order to earn love. Seeing Rembrandt’s depiction of the father, Nouwen collided with his own unfulfilled longing. In an early draft of The Return of the Prodigal Son he gave words to this experience: “It was the gentle forgiving touch of two hands that remained with me, reminded me of a love that cannot be earned or gained, but which is there simply to be received in gratitude.”5

In 1983, the many years of being a pleaser had finally caught up with him. At Harvard, he was lonely and alienated by academic competitiveness. Earlier, as a missionary in Peru (something he tried in the 1980s), his difficulty with the Spanish language precluded deep friendships and meaningful contact. A ten-city speaking tour on a very volatile subject—American complicity in oppressive regimes in Central and Latin America—had left him completely exhausted and burned out.6 On top of all this, the “special love” of his mother had been stilled by her death in 1978.

In his “Returning” retreat, Nouwen reflected on the effect of her death on him:

Although I loved teaching in the universities I was always yearning for intimacy in my life. I found this special love to a certain degree in my relationship with my mother. She loved me in a particular way, followed my every move, faithfully corresponded with me, expressing a love that was so tangible, full and close to be being unconditional. When she died in 1978 during my time at Yale, I grieved her absence in a very profound place inside.… Her absence plunged me into a downward spiral so that my final teaching years at Harvard in the early 1980s were some of the unhappiest in my life. (Home Tonight, xvii)

Nouwen longed for more than his father could give him. He thirsted for affirmation, and at numerous points in his life he found surrogate father figures to meet this need. One example can be seen in a letter he wrote to his friend Richard, a political activist he met in Mexico in the early 1960s:

From the moment I met you in Cuernavaca I have felt a deep and strong attraction to you. It wasn’t a sexual attraction as much as an attraction to your inner strength, your ability to give me affection and care, your interest in me and your opening to me a world of feeling and thought that were very new to me. Your embrace, your touch, your smile, your strong hands, they all gave me a feeling of safety and protection. I often felt in your presence as a child who is safe because daddy’s close. Emotionally I often wanted to be loved by you as by a father.7

Years later, Nouwen was similarly drawn to John Eudes Bamberger, the abbot of the Trappist Abbey of the Genesee in upstate New York, with that similar intensity. His relationship with Jean Vanier can be seen as another example.8 Eventually, Nouwen would finally meet the father figure he needed, but it would not come in the form that he was expecting.