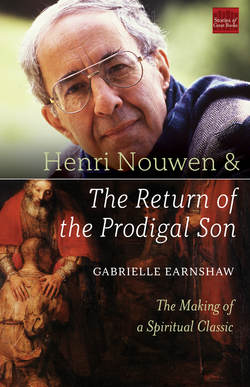

Читать книгу Henri Nouwen and The Return of the Prodigal Son - Gabrielle Earnshaw - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Search for The Father’s Love

ОглавлениеWhile Henri Nouwen’s life can be viewed through the lens of a spiritual quest, another way to see it is as a search for a father’s love—both human and divine.

In The Return of the Prodigal Son, Nouwen mentions his father, Laurent Nouwen Sr., three times. In two instances, the mention is in passing—one is about clothing that his parents bought him, and the second is about looking in the mirror and seeing his dad in his own image. In the third instance, however, Nouwen tells us a bit more about this central relationship in his life. He describes an incident from 1989, when after being critically injured in a road accident near his Daybreak home, he told his father, who had flown from Holland with his sister Laurien to be with him, something he had never shared with him before.

While recovering after surgery, he explicitly told his father that he loved him and was grateful to receive his love. He shared other thoughts and feelings he had never verbalized, and was surprised by how long it had taken him to do so. His father was puzzled by it all, but received his words with a smile. Nouwen experienced this encounter as a “spiritual event” that allowed him to “return from a false dependence on a human father who cannot give me all I need to a true dependence on the divine Father” (Prodigal Son, 78).

We sense that Nouwen forgives his father for not giving him everything he needed, or perhaps that Nouwen has reached a point where he realizes that what he needs is more than any human father could provide. It becomes a pivotal moment in Nouwen’s life.

While this event is told in a few paragraphs in The Return of the Prodigal Son, in early attempts to write the book (which we will look at in more depth in later chapters), Nouwen is more explicit about his experience of his father and male authority figures in general. He writes, “I know the desire to be independent from a father who is strong, powerful and dominating. Whether I speak of my Dad, my bishop, the dean of the school or the leader of the community—there has always been the fearful father who knows things before you have told him, understands before you have explained, answers before you have asked and decides before you have voiced your opinion.”3

While leading a retreat on the prodigal son in 1988 for members of L’Arche, Nouwen fleshed out his experience of his father further. There, he explained that he had always longed for his father’s approval but never seemed to get it.

“You see,” he explained to his retreatants, “my father accomplished his goals late in life by becoming a successful professor of law, and based on his background this rise to fame was quite unusual in his day. My dad was very bright and able to function well in the world of competition. I, as the older son in our family, seemed to be programmed to believe that I had to be at least as good as my dad. Thus began a lifelong competition with respect to our careers and to most other subjects as well” (Home Tonight, 69).

As Nouwen was aware, his experience of his father was unique to him. As the eldest of four children, he would have had a different relationship with his father than would his younger siblings. Peter Naus, a social psychologist who attended seminary with Nouwen and visited the family on occasion, remembers a difficult dynamic in the family in which Laurent Nouwen Sr. was competitive with Nouwen and the youngest daughter, Laurien, but not with sons Paul and Laurent. While basically a loving father, he often responded to Nouwen’s ideas with “I could have told you that long ago!” (see Home Tonight, 69).

Naus observed that it was the role of the mother, Maria Nouwen, to soften the impact of the father. According to Naus, “She represented gentleness.… She brought warmth into the family. When she entered the room there was warmth.”4 Naus also remembers that while Laurent Nouwen Sr. presented an authoritative persona he could also be “mischievous” and “not so serious.”

Laurent Nouwen Sr., like many men of his generation (and ours too), felt intense social pressure to make something of himself. He was successful, but he felt the need to keep working hard to maintain his status. He did what he had to do for his family, but he was not a man of emotions, not one to show his vulnerability. He projected power and strength. He valued the intellect and cerebral pursuits. It is likely he worried about his sensitive and needy son.

In a journal written in the year of his death, Nouwen would reflect on his family dynamic this way:

It was my mother who offered closeness, affection, and personal care. My father seemed more distant. He was the provider who loved his wife, expected much of his children, worked hard, and discussed important issues. A virtuous, righteous man, but I found it difficult to feel intimate with him. (Sabbatical Journey, 81–82)

Laurent Nouwen Sr. may have seemed emotionally distant to Nouwen, but his actions spoke of his love for his son. He visited Nouwen regularly in the United States. He wrote and called frequently. He was always available—just not in the way that Nouwen longed for. Nouwen felt his father didn’t affirm him. He didn’t read his books. He didn’t brag to his friends about his son’s accomplishments the way he did about Nouwen’s brother Paul, who was on the news most evenings speaking as the director of the Royal Dutch Touring Club, ANWB; or Nouwen’s other brother Laurent, a lawyer and partner at the distinguished law firm Nauta Dutilh in Rotterdam.