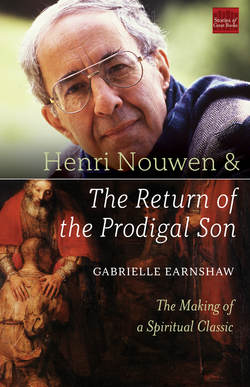

Читать книгу Henri Nouwen and The Return of the Prodigal Son - Gabrielle Earnshaw - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 2 Intellectual Antecedents Visio Divina and the Spiritual Vision

ОглавлениеWhat you carry in your heart is what you see.

(Henri Nouwen)25

One might assume that the Rembrandt painting that struck Nouwen like a “lightning bolt” was a peak experience, a once-in-a-lifetime epiphany. In fact, Nouwen was on the lookout for “glimpses” of God at all times. As I noted earlier, he saw God in a trapeze troupe, for instance, and at the very time Nouwen was transfixed by “his painting,” he was captivated by yet another image. This was a reproduction of a Rublev’s Trinity icon, placed on the table in the room where he was staying in Trosly by Jean Vanier’s secretary, Barbara Swanekamp. The Trinity icon, and other icons after it, became so connected with Nouwen’s spiritual life that in 1987, five years ahead of The Return of the Prodigal Son, he would publish a book about them. That book, Behold the Beauty of the Lord: Praying with Icons, is important because it shows us how Henri Nouwen saw art and explains his capacity to enter so fully and fruitfully into the painting by Rembrandt.26

Behold the Beauty of the Lord was published in February 1987 by Ave Maria Press. It explores the power of looking at religious iconography in the Eastern Orthodox tradition and is structured around Nouwen’s meditation on four icons and the meaning he found in them. As iconographer Robert Lentz pointed out in the foreword, it is not a scholarly work (though Nouwen prepared for the manuscript by reading deeply into the subject); it is a response of his soul (Behold, 11).

For Nouwen, icons allowed for transcendence without language and thought. He suggests that when we are tired, restless, or depressed, when we can’t pray, read, or think, we “can still look at these images so intimately connected with the experience of love”27 (Behold, 20).

In addition to helping us pray when we don’t have words, Nouwen’s book teaches us that we can choose what we see. We can take conscious steps to safeguard our inner space. Nouwen recognizes that we are bombarded with images, many of which are damaging, and we must be vigilant about where we put our attention. He writes, “It is easy to become a victim to the vast array of visual stimuli surrounding us. The ‘powers and principalities’ control many of our daily images. Posters, billboards, television, videocassettes, movies and store windows continuously assault our eyes and inscribe their images upon our memories.… Still, we do not have to be passive victims of a world that wants to entertain and distract us. We can make some decisions and choices” (Behold, 21).

Nouwen suggests that we commit images of art to memory, similar to how we might memorize the Jesus Prayer or passages from the Psalms. We memorize them to bring to mind when we need them. Nouwen, for instance, memorized work by Rembrandt and Vincent van Gogh. During his “Returning” retreat, he shared, “These Dutch painters have entered my heart in a very deep way, so I have them in my mind as I speak to you. They have become my consolation and when I find I have nothing to say, when I have only tears for what is happening in my life, I look at Rembrandt or at Van Gogh. Their lives and their art heals and consoles me more than anything else” (Home Tonight, 13).

When Nouwen was a child, the Nouwen family owned an original watercolor by Marc Chagall of a vase of flowers standing in front of a window. It was purchased by Nouwen’s parents, Maria and Laurent, in Paris, shortly after their wedding and before Chagall’s international fame. It hung in the family living room while Nouwen was growing up. Nouwen says that the painting, closely associated with his mother, who loved it very much, had imprinted itself so deeply on his inner life that it appeared every time he needed comfort and consolation. “With my heart’s eye I look at the painting with the same affection as my parents did, and I feel consoled and comforted” (Behold, 19).

Visio divina, or “divine seeing,” is an ancient contemplative practice that invites the practitioner to encounter the divine through images. Sharing roots with the practice of lectio divina—the practice of reading Scripture and then holding what one has read in the heart and contemplating it from there—visio divina is an interaction with an image to create a powerful experience of the divine. Practitioners of lectio and visio divina use the imagination to become each person in the story or image, to feel what they are feeling, to think what they are thinking, and to experience what they are experiencing.28

Visio divina as explained by Nouwen is more about gazing than looking. Instead of a kind of scrutiny, judgment, or evaluation, gazing is gentle, and allows for revelation. “Gazing,” Nouwen explains, “is probably the best word to touch the core of Eastern spirituality. Whereas St. Benedict, who has set the tone for the spirituality of the West, calls us first to listen, the Byzantine fathers focus on gazing” (Behold, 22).

One day, Nouwen and his friend Sue Mosteller decided to go to the art gallery together. Nouwen was excited to show her a Vincent van Gogh painting of which he was particularly fond.29 Nouwen bounded up the gallery steps and headed straight for the painting. It was in a small frame and depicted a field, trees, and flowers. Nouwen sat down on a bench in front of the painting and Mosteller sat down beside him. Nouwen stared at the painting with a look of deep concentration. Mosteller looked at the painting, too, but after a few minutes was ready to get up and move on. Nouwen, however, continued to gaze. Mosteller tried to see whatever it was that he was seeing. She examined the details one by one, the composition, the brushstrokes, but after a few minutes, she again grew restless. “Henri!” she finally said, “What are you doing?” Nouwen turned to her in surprise and said, “I am in the painting! I am in the South of France and it is so beautiful. Aren’t you? Look at the colours! Look at the light!”30

This story allows us to speculate that Nouwen saw with a kind of spiritual vision. He could look at the world through the eyes of his heart, and perhaps even sometimes with the eyes of God. It was a practice he consciously cultivated. When Nouwen saw the little poster in Landrien’s office, he didn’t simply see a beautiful painting—he walked through the gate and into the outstretched arms of the father.

Nouwen was attuned to art through birth and culture. He was born in the land of the seventeenth-century Dutch masters, including Rembrandt and Johannes Vermeer, as well as famous Dutch painters of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries: Vincent van Gogh, Piet Mondrian, and M. C. Escher. Nouwen would have been immersed in these paintings as a child and young man. As an adult, he felt a particular affinity with two of these artists: “I am a Dutchman, Rembrandt is a Dutchman and van Gogh is a Dutchman.… They are confrères” (Home Tonight, 13).