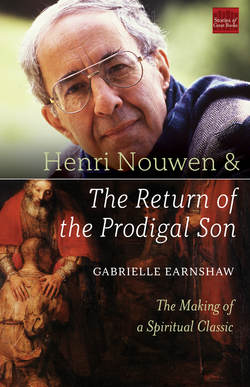

Читать книгу Henri Nouwen and The Return of the Prodigal Son - Gabrielle Earnshaw - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction

ОглавлениеThe same year Henri Nouwen published his masterwork The Return of the Prodigal Son he turned sixty years old. To celebrate this milestone birthday, the L’Arche Daybreak community, where Nouwen had lived for the previous six years, planned a special party for him. As part of the festivities, Robert Morgan, a friend of Daybreak and a professional clown, asked Nouwen to dress up in blue balloon pants with a matching shirt and a ruffled burgundycolored collar. Robert placed a beanie on Nouwen’s head and had him crawl into a large sack that was dragged to the middle of a large room. Giggles erupted from the gathered audience of his Daybreak friends. Then, with some instruction from Robert, Nouwen began to emerge from the pulsating sack. At first, all you could see was a skinny, bare foot poking out. Then, with his natural flair for the dramatic, Nouwen started making little chirping sounds as he stuck out more limbs. Finally, Nouwen sprang out, leapt to his feet, raised his enormous hands in the air, and gave the audience the wide-eyed, delighted look of a child. His rebirth as a clown was complete.

A video recording of this birthday drama is preserved in the Nouwen Archives at the University of St. Michael’s College, Toronto. It reveals how natural this shift from adult man to baby clown was for Nouwen. His sense of play was matched only by his capacity for understanding the symbolism he enacted. Later that evening, speaking to Daybreak friends about the party, he expressed his deep gratitude to them: “You know me. You really know me.” And they did. After years of searching, Nouwen had found his home.

The clown birthday is a vivid metaphor for a spiritual rebirth that began for Nouwen in the fall of 1983 when, exhausted and adrift, he first saw the poster that would change his life: The Return of the Prodigal Son by Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn.

At the time, Nouwen was living at La Ferme in the village of Trosly-Breuil, France, spending a few months at L’Arche, a community that offers a home to people with intellectual disabilities. He was there to recuperate from an extensive US speaking tour he had just completed before he moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he would join the faculty at Harvard Divinity School for the 1984 fall semester. One day, he went to visit his friend Simone Landrien in the community’s small documentation center and saw the Rembrandt poster pinned to her door. All Nouwen saw at this moment was a boy being embraced by a gentle father. As he shares so vividly in his book, a flood of emotion overwhelmed him and awakened a yearning for love and safety that would shape the course of his life for years to come.

This encounter with the Rembrandt poster marks the genesis of his spiritual classic The Return of the Prodigal Son: A Story of a Homecoming, a book that reached “term” nine years later after a series of life-altering experiences. Nouwen would leave Harvard, suffer a nervous breakdown, survive a life-threatening accident, reconcile important relationships, and perhaps most importantly, join the L’Arche Daybreak community in Toronto as pastor. Nouwen had to live the painting before he could write about it.

The Return of the Prodigal Son captures Nouwen’s wisdom on the questions that animate many of us: Who is God? Who am I? How should I live? He writes on identity, God, relationships, and above all, the unifying, undergirding nature of love itself. It is the book that most fully expresses his long journey to freedom.

What is this freedom? According to Nouwen, it is to enter a second childhood as expressed by Jesus, who said, “Truly I tell you, unless you change and become like little children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven” (Matthew 18:3). It is a movement away from compulsions and addictions to a life of spiritual maturity, one in which we forgive others, serve them, and form a new bond of fellowship with them.

To enter a second childhood while claiming a new adulthood is to live a paradox. We can allow ourselves to be more childlike (in contrast with childish) in our approach to life. We can live our mature years with renewed wonder and awe. We can shed aspects of ourselves that we no longer need, and unify the essentials left over once the stripping is done. Entering a second childhood is to integrate all that we have experienced into a whole—and enter life as though born again.

In The Return of the Prodigal Son, Nouwen lets go of the compulsion to run away from difficulties, to hold on to fear, to cling to resentment and childish fantasies. By letting them all go he comes home to himself. Gradually, he steps into an entirely new way of being. He becomes as the Father in the painting, a blessing and vessel of love to the world.

This is not to say that Nouwen’s journey was easy. As readers, we are awed at the way he shares his vulnerability and neediness along the way. Yet, we sense Nouwen’s strength and resolve to persevere in his search—not for an outward prize, but for the reward of allowing himself to be loved by God. At the end of the book, Nouwen is not perfect, nor is the journey over, but he has been changed.

Nouwen shows us that we too can return home. We have not ruined everything with our bad choices, doubts, or shortcomings. We can start again. We can be reborn. And our loving God will run to meet us.

The book speaks to the many people who feel unworthy of being received back by God after turning away. One critic suggests that The Return of the Prodigal Son is a book “for sinners,” in that it resonates with people who feel that they have failed God in some way and are unworthy of God’s attention and love. Nouwen offers a new image of God that many of his generation wouldn’t recognize—a God who is merciful and unconditionally loving. A God who uses power not to control or dominate but to restore, console, and bless.

Nouwen’s road to the insights he had about the parable was a long one. This book is about how he got to the point where he could say, “I will be the father even while I know it will be a most dreadful emptiness.” This is a surprising conclusion to draw from the parable. Where did this insight about spiritual maturity come from? Where did he get the strength for this courageous choice? What happened in the years between seeing the poster for the first time when he yearned to be enfolded in the arms of the loving father—to the realization that he was being called to be the father? Between yearning to be blessed to being the one who blesses? What happened in his life to allow such profound insights into the heart of the son, the elder brother, and finally the near-blind father?

In the first chapter, I explore what led to the moment of Nouwen’s collapse in front of the poster. What primed him to be so ready to see the poster as “his painting”? I explore his earliest relationships with his family in the Netherlands and how as a sensitive child, patriarchal norms of fatherhood and hands-off mothering philosophies of the time created perfect conditions for neediness and anxiety in Nouwen. We will see that this led to patterns of trying to please others in order to get the sense of safety and love that he craved. Nouwen was lonely when he saw the poster for the first time. He needed the love of a gentle father. He was also grappling with his sexuality as he lived his vow of celibacy. As you will see, Rembrandt’s painting was a doorway to reconcile these fragments of discontent and unease.

Chapter 2 is about Nouwen’s intellectual formation and how it informed The Return of the Prodigal Son. What people, methods, and theories influenced how he wrote about the painting? I look at how Nouwen used visual art as a means of understanding his life and the world. Art fed his spiritual vision long before he saw the poster. We will see that visio divina, an ancient contemplative practice of encountering the divine through images, informed his reaction to the painting and gave him the ability to see it with the eyes of his heart. He could enter into the Rembrandt painting so fruitfully because he had been cultivating a spiritual vision for decades before he saw it. Next, I explore the foundational importance of Anton Boisen to Nouwen’s life and thought. Boisen is considered by many to be the father of pastoral theology. It was Boisen who introduced Nouwen to the concept of studying people as “living human documents.” This approach of listening to, analyzing, and understanding people’s life stories fed into all of Nouwen’s later work. One cannot understand Henri Nouwen or his interpretation of Rembrandt’s painting without examining the work of Boisen.

The third chapter addresses Nouwen’s writing process. What went into writing the book? How many drafts did it take? Who helped him? What was happening in his life in the nine years that it took to complete it? This chapter is informed by a careful analysis of early drafts of the book as well as an examination of the letters exchanged between Nouwen and his publisher at Doubleday and other important parties. With these archival sources, we are able to get inside the process as it was unfolding, particularly the primary importance of his friend Sue Mosteller, a sister of the Congregation of St. Joseph and member of L’Arche Daybreak, who pushed Nouwen to claim his identity as the father. We see through an intimate exchange of letters between Mosteller and Nouwen, all of which are being published here for the first time, how central she was to the writing of the book. This chapter also explores the historical context of the book’s publication. Whereas the first part of the chapter zooms in on the progress of the book from genesis to publication, this section zooms out to place The Return of the Prodigal Son in its broader social and cultural context. What other books on similar themes came out around this time? How did Nouwen’s book compare? In what ways was he speaking to the zeitgeist? I notice that in 1992 the “boomer” generation was longing for new ways to express and feed their spiritual impulses. I show that Nouwen spoke to this generational need and gave them a revised image of the Divine that spoke to their desire for a God of compassion. I show how he gave them (and us) a new entryway into the beauty and scope of Jesus’s message of love. You will see that while Nouwen’s very Christian and Jesus-centered book precluded acclaim by popular culture, it shared many characteristics of the selfhelp and “spiritual but not religious” works of the time, particularly those that, like The Return of the Prodigal Son, drew on psychology, parables, and archetypes to speak to the needs of the day.

The fourth chapter focuses on the book’s impact. How did critics respond? What did his readers have to say? We see that although the book did not receive much attention from the media, reader response was enthusiastic. I look at letters that Nouwen received from his readers and draw out some of the most common reactions. We hear from a prisoner in Ghana whose experience of solitary confinement was changed by his reading of the book, from mothers and fathers struggling with estrangement from their children on how the book gives them courage to wait in joy rather than anger or fear for their return, and we learn of the many people for whom the book changed their relationship with God, and also with themselves. The book opens doors for readers to claim their worthiness of love.

We also look at letters from a minority of readers who were more critical. “Why don’t you look at the female figures in the painting?” wrote several women. “Your depiction of the prodigal son’s return celebrates his ‘being tamed.’ Why does religion smother his youthful, spirited, passionate impulses?” asked one reader. This chapter concludes with a look at the book’s more famous readers, as well as other indicators of how it has inspired contemporary artists to express their experience of the parable and the painting.

Chapter 5 covers Nouwen’s life after the book was published. What impact did it have on Nouwen’s life? Was his aspiration to claim fatherhood ultimately lived out? We see that indeed Nouwen’s life was transformed by “his painting” and that while he never completely overcame his struggles, he was able to live them in a new way. We hear testimonials from people who lived with him after the book was written who describe his almost insatiable desire to welcome and bless members of his Daybreak community. He proclaimed the truth of their belovedness with deep conviction and even urgency. We see that his writing vocation accelerated; he wrote eleven books in four years. This chapter ends with a glimpse of a new “painting” that captured his imagination—a trapeze troupe. His imagination, having absorbed all he could from the Rembrandt image, was captivated by a new expression of God’s reality in our lives.

The final chapter looks at where we are nearly a quarter century later. The Return of the Prodigal Son is Henri Nouwen’s bestselling book. It has sold more than one million copies worldwide and has been translated into thirty-four languages. It continues to outsell all his other books. What accounts for the book’s lasting influence? In what ways is it dated? Prescient? Is it relevant for today’s seekers? I begin by considering Nouwen as prophet, in the sense that he holds up a mirror to ourselves and also to the societal norms of our day. He helps us see our infatuation with youthfulness, our propensity for self-rejection, and how our norms of masculinity distort our image of God. I conclude with speculation rather than answers. I have noted that in subtle ways, The Return of the Prodigal Son indicates that Nouwen seems to have been heading into a territory beyond religious literalism and a gendered/binary God—a direction that many today will welcome and others will find challenging. But this is only my opinion, and as readers of The Return of the Prodigal Son will appreciate, you may disagree. But this is not a problem. This is an invitation to strike your own path toward a life filled with love, hope, and meaning.