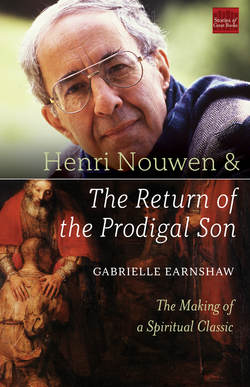

Читать книгу Henri Nouwen and The Return of the Prodigal Son - Gabrielle Earnshaw - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Fathers and Sons

ОглавлениеTo understand Nouwen’s longing for intimacy with a loving father in a more rounded way, we need to consider the context of the times in which he lived. What were the societal norms around displays of affection between fathers and sons? How did society regard men who showed their emotions or vulnerabilities? Patriarchy has historically dictated that men behave in a certain way. Society says, “Real men don’t cry” and “Act like a man!”

Perhaps not much has changed. Even today we live in a society that longs for a father’s loving touch, and we see very little of it around, particularly between fathers and sons. We are generations of children longing for a gentle father. What role models do we have today for fatherhood? Nouwen was asking similar questions in the early days of his academic career.

In 1970, Nouwen published an article called “Generation Without Fathers” in Commonweal magazine. He was teaching pastoral theology at the University of Notre Dame while holding a similar teaching position at a seminary in Utrecht, the Netherlands. The article is about Christian leadership in an era of unprecedented anti-authoritarianism in the West. Nouwen draws on psychological training he had taken after ordination to identify a new Western phenomenon—young people were no longer looking to traditional authority figures for help. They saw their parents as complicit in the atrocities of the world wars, powerless in the face of nuclear and environmental threats, and narrow in their worldviews. They were ready to abandon the Father completely and chart their own way in the world.9

Nouwen, one with this generation and also its observer, described it this way: “[There is] no desire anymore to leave the safe place and to travel to the father’s house which has so many rooms, no hope to reach the promised land or to see Him who is waiting for his prodigal son, no ambition to sit at the right or the left side of the Heavenly Throne.”10

Some two decades after he wrote this, Nouwen was still circling the question of how to reconcile with the Father, both personally and in the broader context of society. This time, twenty years older and now entering middle age, he focuses not on youthful rejection of the father but the moment we heed the call of homecoming and come face-to-face with the Father. In this sense, The Return of the Prodigal Son is the story of a generation reexamining its relationship to God and authority figures. Nouwen, using his own life as an example, shows that we can stop behaviors that keep us in perpetual distance from the Father. We can accept our sonship or daughtership without losing our freedom. And eventually, we can take our place not “at the right or the left side of the Heavenly Throne,” but as Father/Mother ourselves.

Recently, two Catholic thinkers, Laurence Freeman of the World Community of Christian Meditation, and Richard Rohr, the popular Franciscan friar and priest, used social media to remind their followers that our propensity for conflating our images of father and God comes from long-held belief in a punitive God that must be appeased with sacrifice.

Freeman wrote,

Much more often, our image of God is related not to those experiences of love, of joy, or of union, but it’s related to experiences of authority and punishment. A young child is taught to think of God as a sort of super parent. The very word we use about God, of course, Father, carries with it, in most children’s upbringing, an image of a person in the family who does the correction, who does the discipline. The idea of God as Father carries with it, therefore, this sense of control, this sense of dominance. And where there is punishment or this kind of relationship to authority, there is usually fear. We fear being punished, we fear being sent to hell.11

Rohr put it this way:

In authoritarian and patriarchal cultures, most people were fully programmed to think this way—working to appease an authority figure who was angry, punitive, and even violent in “his” reactions. Many still operate this way, especially if they had an angry, demanding, or abusive parent. People respond to this kind of God, as sick as it is, because it fits their own story line.12

As both Rohr and Freeman say, it is deep within our collective and individual psyches to think of God as a punitive parent. The Return of the Prodigal Son is so powerful because Nouwen, without speaking a word of theology or history, addresses this metanarrative with a gentle story of his own. He invites people to listen to his own experience of releasing this shaming image and to embrace an image of a feminine/masculine creator who envelops us in unearned, unconditional love. Nouwen uses the power of story to help us revise our image of God so we can allow God’s love to enter our lives with freedom and even joy.