Читать книгу The Hidden Musicians - Ruth Finnegan - Страница 18

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление4

The classical music world at the local level

Classical or ‘serious’ music is what many readers will first think of when music is mentioned. For its participants this is the world of music, the type of music which in its repertoire, teachers, and performance is music par excellence, validated through state and church patronage and by its acceptance as part of the artistic heritage of European Christian civilisation. As one of the central cultural traditions of our society perhaps it seems too familiar to need explication. But one aspect that is often overlooked is the role of the amateur musicians and their local activities. This chapter describes some of the local practices and practitioners within classical music, the way these relate to the wider classical model, and the essential contribution they make to the continuance of classical music as a performed art form.1

The local activities and groups within this classical music world took various forms. There were the occasional visits of famous professional orchestras and soloists to give performances in one or other of the local halls, and concerts by local orchestras and choirs with visiting professional soloists. Local pupils from time to time went on to professional music training at one of the specialist music colleges outside the area after initial instruction by local teachers. But these more spectacular events were only part of the picture, for there were also the ‘lesser’ local activities that on a day-to-day basis both reflected the ideal classical model and, ultimately, enabled its realisation in practice.

School music was one important element. In addition to formal music lessons, children’s ensembles played regularly outside lessons, and schools put on concerts for parents and friends (described further in chapter 15). The Buckinghamshire Education Authority also ran two music centres (one in Bletchley – the North Bucks Music Centre – and one at the Stantonbury Education Campus) which organized peripatetic instrumental teachers for local schools and ‘Junior Music Schools’ on Saturday mornings where local children played in groups or gave regular termly concerts (see figure 8). Like the schools, these centres were predominantly in the classical (and to a lesser extent brass) tradition, and also encouraged classical musical activity by teaching and by providing rehearsal facilities and other services for classical groups. They formed one local nucleus of musicians, many also functioning as private teachers or members of local orchestras, choirs and other ensembles.

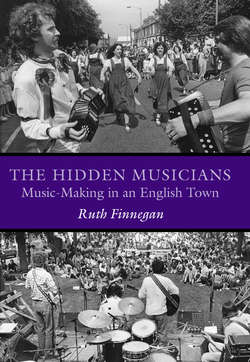

Figure 8 The North Bucks Youth Orchestra (one of the many junior orchestras at the North Bucks Music Centre) perform Swan Lake at their termly concert accompanied by local dancers

There were also the many private music teachers and their pupils. They too played a part not just in socialisation into music but in the actual music-making of the locality, hundreds of hours of playing every week. There were scores of instrumental and singing teachers with varying qualifications, above all in piano teaching, and each year about a thousand practical music examinations for the national examining schools were held in local centres – some indication of the extent of classical music. Private music teaching, especially to children, was a flourishing industry with pupils of varying levels of proficiency playing musical instruments not only to their teachers but also at school or church, in local groups and in the home.

The churches were another context for the local enactment of classical music. Many had their own choirs, together with one or more organists who played from the recognised classical repertoire on church occasions, including the life-cycle ceremonies so often held in church – christenings, weddings, funerals. It was thus through the churches as much as through formal concert halls that many people came to appreciate the large proportion of the classical musical heritage that is so closely associated with the Christian tradition, and themselves actively participated in it (see further in chapter 16).

A further essential part in the local enactment of classical music was played by the local groups formed to promote or perform music. The extent and scope of these active musical groupings, and the systematic conventions by which they organised their music, may well surprise those who bemoan the disappearance of active music-making today, or the ‘cultural desert’ in our cities. Let me illustrate this by some description of the local orchestras, instrumental ensembles, and choirs.

First, the orchestras. The best known was the Milton Keynes Chamber Orchestra, founded ‘to provide a regular series of high quality professional concerts in the new city’ as part of MKDC’s strategy for making the city a centre for artistic excellence. As described in chapter 2, this soon became recognised as a professional orchestra, with national as well as regional connections, and many of its players lived outside Milton Keynes. As such it does not really come within the scope of this study, but did have some relevance in that its regular local rehearsals and performances provided one model for younger instrumentalists as well as a focus for local audiences keen on hearing professional playing.

Among the other orchestras the highest in the classical hierarchy was the Sherwood Sinfonia (figure 9). This was founded in 1973 as a high-standard amateur orchestra for the area and by the 1980s was playing regularly under a professional conductor. Local music teachers made up a substantial proportion of its members and recruited their advanced pupils from local schools, supplemented by other experienced players from the area, playing the typical classical orchestral instruments: strings (violins, violas, cellos, double bass), wind (flutes, oboes, clarinets, bassoons, trumpets, horns, trombone and tuba) and percussion – about 55 players in all. Membership was restricted to those with the appropriately high-level qualifications, the accepted criteria being high grades reached in the nationally recognised examinations, personal recommendation by an existing member (especially the music teachers) or in some cases audition. In keeping with the classical music tradition, the orchestra had enlisted a nationally known and highly qualified musician as their President, his name printed in its full glory on the orchestra’s letterhead: Sir Thomas Armstrong, MA, D. Mus. (Oxon.), Hon. FRAM, Hon. FRCO, Hon. FTCL.

Figure 9 Christmas concert by the Sherwood Sinfonia. The leading amateur orchestra rehearse for their concert with the St Thomas Aquinas school choir at Stantonbury Theatre

The Sherwood Sinfonia were a serious and committed orchestra which took justifiable pride in their high standards, and at the same time remained very local in their playing, membership, audiences, rehearsals and performances. They gave about four concerts a year in local halls, mostly playing works from the accepted classical repertoire by composers like Mozart, Dvořák and Brahms, though for their light-hearted Christmas family concert, they chose lighter pieces together with joke items, quizzes, or audience-sung carols. As with most groups of this kind, they moved through a repeated annual cycle: the weekly rehearsals were climaxed by the intensive activity leading up to the regular concerts, each preceded by its three-hour afternoon rehearsal and culminating in the evening performance in front of an audience largely made up of friends and relations. In the early 1970s the Sherwood Sinfonia was described as ‘the classical musical activity in the town’, and even ten years later, despite the founding of the Milton Keynes Chamber Orchestra, it had not wholly lost this position.

When orchestras and ensembles were graded in typical classical fashion by their playing and performing standards, other orchestral groups were reckoned lower in both expertise and aspirations. There were the Newport Pagnell Concert Orchestra (founded in 1980) and the older Wolverton Light Orchestra, both expecting to recruit players who were of reasonably high standard (the national Grade VII examination was mentioned as desirable for the former, for example) but were perhaps not experienced enough for the Sherwood Sinfonia or just preferred a different kind of musical expression and atmosphere. Some individuals played in more than one orchestra, often choosing to go to the Wolverton Light Orchestra with their second instrument ‘for fun’. These orchestras had the same general range of instruments but were smaller and more locally orientated than the Sherwood Sinfonia. They relied on local soloists and conductors rather than professionals from outside, and appeared at smaller local venues like churches and community centres, often with a special emphasis on raising money for local charities. But they too were definitely part of the classical music world, playing with no small degree of lengthily acquired proficiency on classical instruments. It was through them, and those like them, that this classical tradition was in practice maintained at the grass roots, part of the long-flourishing continuity of British amateur music-making.

There were also other more fluid instrumental groups. Some were initially scratch groups who had joined up for some festive occasion or to accompany a local choral performance, like the North Bucks Music Centre Orchestra (accompanying the Sherwood Choir), the Simon Halsey Orchestra (with the Milton Keynes Chorale), or smaller ensembles like the Wavendon Festival Strings, Walton Festival Strings or Cavatina Strings. There were also 25–30 school orchestras, together with three or four ‘Saturday music school’ orchestras in each of the two music centres, with their gradually changing membership as children worked through the various grades.

Each of these musical groups – which may sound uninteresting in a bare list – was made up of active and cooperating individuals. Each involved an immense amount of commitment and skill, and the co-ordination of quite large numbers of people (even the Saturday junior orchestras could contain 30 or 40 children/teenagers). All depended on voluntary participation by the players, time that could equally well have been spent on other activities.

There were also smaller classical instrumental groups, though their numbers and importance seemed to be nowhere near those of the more ‘popular’ bands discussed in later chapters. Classical groups did not have the same recognised public outlets as rock, jazz or folk groups, they tended to play in private – thus unknown to others – and perhaps instrumentalists in the classical tradition found individual or orchestral playing more satisfying than chamber groups. However, there were some small groups, not all long-lasting. These included the Bernwood Trio, the Milton Keynes Baroque Ensemble, the Syrinx Wind Quartet, the Syrinx Wind Octet, the Baroque Brass Ensemble, the Seckloe Brass Ensemble and – in slightly different vein – the Milton Keynes Society of Recorder Players, who played monthly in Walton Church. Most of these were amateur (though some were mixed or ‘semi-professional’, i.e. with local music teachers) and, being small, had no need for the formal conductor expected in the larger groups. In addition there were fluid private arrangements by which people met in each other’s houses – preferably one with a piano – to sing or play together.

To many English readers, the existence of these orchestral and instrumental groups may in a way seem scarcely worth remark – a natural part of local classical music and of English urban life. But this active instrumental activity at the grass roots is not found everywhere. It has sometimes been claimed that the success of English players in European youth orchestras is due to the distinctive English development of local- (not just national-) level playing, with school, youth and adult amateur orchestras in just about every English town. The orchestral and other instrumental groups in Milton Keynes both followed out this taken-for-granted pattern and played an active part in its continuance.

The local choirs made up the other main strand in the classical music world, a natural outgrowth of the strong choral tradition in the area. Besides the many church and school choirs there were also independent choirs, each with their own conductor or musical director (usually male and with formal classical training), which often contained at least a scattering of music teachers and of experienced choral singers. The leading choirs in this mould were the Milton Keynes Chorale and Danesborough Chorus (each with 80-plus members, and often appearing on large city occasions like the prestigious February Festival) and the smaller Sherwood Choral Society (30–40 members: see figure 29 and further discussion in chapter 18). Some continued the tradition of the older locally based choral societies, like the Newport Pagnell Singers, with their roots in the Wolverton Choral Society, dating back to early in the century; the Stratford Singers at Stony Stratford (see figure 20), ‘one of the most popular choirs in Milton Keynes’, according to the local newspaper, formed in 1974 ‘to sing together for our pleasure and that of the audience’; and, until it ended in 1980, the Bletchley Ladies Choir, dating from the 1940s.

Most larger choirs were (like the orchestras) based on the accepted British ‘voluntary association’ model, with written constitution, elected officers and committee, formalised membership subscriptions and accounts, and Annual General Meeting. They normally rehearsed one evening a week throughout the year with a break in the summer, meeting in one or other of the local halls or in village, school or community meeting-places. They had broadly similar yearly cycles. A Christmas concert was usually one high point – so much so that a city-wide committee tried (not altogether successfully) to arbitrate between choirs’ claims for the same Saturday evenings in December. There was also often a major concert in the spring or summer, with occasional smaller performances at other times in the year.

Each was worked for according to an accepted routine of rehearsals and performance. It started with detailed practisings of isolated parts of the works under the conductor (and perhaps his or her assistant), singing to piano accompaniment, then moved gradually towards consolidating the piece as a whole, culminating in the intensity of the later rehearsals when the work began to ‘come together’, then the great but sometimes traumatic rehearsal on the afternoon of the concert (often a revelation to the choir as for the first time they heard the whole work complete with solos and full accompaniment). Last came the experience of the full evening performance before an audience.

This cycle of rehearsal-performance was a recurrent one, especially when, as commonly with the large choirs, the music came from the renowned classical repertoire of oratorio and church music. These were mostly four-part works, ideally with orchestral accompaniment and visiting soloists, by such composers as Handel (Messiah was still one of the great popular pieces, the music known to most singers), together with Haydn, Mendelssohn, Brahms, Bach, Vivaldi, Fauré, and others in the recognised classical canon whose works were over the years sung alternately by the various local choirs. These formed the core of the expected choral repertoire, but there were also concerts of more modern works, especially English compositions by, say, Vaughan Williams or Britten, ‘light classics’ by Bizet or Sullivan, and arrangements of both popular and esoteric carols. Many choir members were already acquainted with much of the classical repertoire (some had been choral singers for 30, 40 or even 50 years). At the least, they had long-practised skills in sight-reading from written music (an essential requirement for every choir) and in recognising familiar cadences and styles. The classical ideal in terms of repertoire, highly graded direction, and aspirations to a ‘high-standard’ performance was very much to the fore, expressed through the actual singers on the ground who had gained their expertise through a process of informal learning and practising in the amateur tradition.

The same general patterns were also followed by the many smaller choirs like the Orphean Singers, Fellowship Choir, Guild Singers, Canzonetta Singers, Miscellany, St Martin Singers, Woburn Sands Band Madrigal Group and the all-female Erin Singers. Many of these continued over the years, but there were also shorter-lived groups like the New City Choral Society, the Bletchley Further Education College Choir and some who appeared under fluctuating names (the Senior Citizens’ Choir developing into the Melody Group, for example). There were also temporary groups who sang together just for a particular occasion, whether large, like the 180-strong Festival Choir (the joint Danesborough Chorus and Milton Keynes Chorale) at the 1982 Milton Keynes February Festival, or small, like the Village Maidens from the local Women’s Institute, who sang after a Christmas pantomime at Stoke Hammond School, and, finally, the various madrigal groups that formed from time to time. Many smaller choirs put on several small events during the year rather than working up one or two main works on the model of the rehearsal–performance cycles of the larger choirs, and sang frequently at churches, fêtes or clubs to raise money for some local good cause or provide entertainment at hospitals or old people’s homes. But here too there was still a stress on rehearsing to reach as high a standard as possible, almost always with a piano accompaniment and under the direction of a conductor. The different categories shaded into each other, of course, and some small choirs had highly qualified conductors or practitioners in classical music terms (the Open University Choir, for example, or the Tadige Singers), but in general the smaller choirs laid less emphasis on specialist classical training and (unlike the larger, more ambitious choirs) quite often had female conductors.

The number of choirs in the area was thus great. There were perhaps 100 in all, with membership ranging from 90 or so down to around 12–15 (a not uncommon number for the smaller groups), or as few as 5 or 6 in some church choirs. The total number of choral singers in the area was thus probably well over 1,000, though it is hard to calculate exact numbers because of the amount of multiple membership – another notable feature of the choral tradition.

These many choirs and instrumental groups practised through the year without always being especially noticeable except to those most directly involved. However, there were points in the year when their activities became more prominent. At Christmas practically every choir and orchestra gave performances, and there were also a great many concerts towards the end of the summer term in the school year. Easter too had its performances, together with other key festivals in the Christian year (especially, but not only, by the church groups). Another high point was February. The annual ‘February Festival’, initially promoted by the MKDC arts division, included both nationally and internationally known professional artists from outside the area, and a few of the leading local groups.

February was also the month of the Milton Keynes (earlier Bletchley) Festival of Arts, a more modest and locally generated event, which followed the established music festival tradition of competitive classes in music, dance and speech for both children and adults in a wide range of ages and standards, judged by visiting adjudicators. It included classes for solo singers and performers on just about every classical instrument, band, recorder groups, small ensembles, and church choirs. The largest choirs and orchestras did not enter, but the festival still provided a showpiece of the classical music world in Milton Keynes. Over the days of the festival, many hundreds of entrants came forward and performed in two Bletchley halls, from piano classes for tiny tots to ‘recital classes’ by young aspirants for music college entrance. The festival had grown from one day in 1968 to an event of more than a week and over 3,000 entrants (almost 80 per cent of them local) by the mid 1980s.

But a mere catalogue gives no real taste of what these many musical activities meant to the participants. This was something over and above the time and work they put into them or the incidental results (sociability or friendship or status) that certainly also often flowed from them. The rewards for those committed to the classical music world are hard to capture in precise words, but they certainly included a sense of beauty and fundamental value, of intense and profoundly felt artistic experience which could reach to the depths of one’s nature. For participants in this world there was perhaps nothing to equal the experience of engaging in a beautiful and co-ordinated performance of some favoured classical work, whether in practice or (at a heightened level) in public concert: the expectant thrill of players or singers entering a hall in their special dress ready for performance, the familiar and evocative sounds of tuning up in front of the audience, the hushed moment as the performers gathered themselves to start or the conductor called all eyes by lifting his baton, and the split second of silence (more of symbolic quality than measured time) at the end before performers and audience returned alike to the everyday world. For those steeped in the classical tradition these richly symbolic moments were experienced as somehow implicating the deep core of people’s being.

This experience was not, ultimately, dependent on the super-high professional standards insisted on in the elite national music world. It was something within the compass and imagination of the quite ordinary part-time musicians in the local halls and schools and churches.

These locally practising musicians were of course influenced by many things, social as well as musical, and it would not do to give either too purist or too generalized a picture of what drew each to his or her musical engagements or the views each held of these. One aspect, however, which to some degree or other set them within an overall common background was the general evaluation of the place of classical music in our culture and the model most people had of this. These shared assumptions were usually implicit only, but some brief (if simplified) comments on this model of classical music are relevant for understanding the local scene, even though to many readers they may seem too obvious and ‘natural’ to need stating.

The musical organisation, artistic forms, and personnel associated with classical music in the broad sense of that term2 were widely, if rather vaguely, assumed to be bound up with many privileged institutions and values of our society: the educational system, church and state functions, and the generally accorded status of a ‘high art’. This status was further supported by the existence of specialised musicians who had managed to establish themselves as a recognised profession with control over recruitment and evaluation. The performances and high-level teaching provided by these experts formed the most visible element in what was accepted as the classical music world. The model of classical music in English society was explicitly defined by the specialists in terms both of the kind of music played – most typically performed in a formal public concert – and its historical and theoretical basis.

There were many detailed differences within this overall world, not least the changing historical styles as analysed in advanced musical studies, but in general terms the current idea of the European classical music tradition, as distinct both from non-European music and from ‘popular’ forms, centred round transmitting the works of influential musicians from the past – the ‘great composers’. Musical genres have of course varied at different historical periods, but those commonly cultivated in local (as in national) performances included orchestral symphonies, suites and concertos, instrumental sonatas, oratorios and classical operas, and vocal music of various kinds, usually with instrumental accompaniment and with the underlying idea that their central essence could be – and was – represented in written scores. There were also classical compositions for particular instrumental combinations from recorder groups to string quartets and instrumental duets, following accepted conventions about both the instruments (specific types of strings, wind and keyboard together with the voice and to some extent percussion), and about how they should be played.

In practice what was classified as within this classical tradition depended not so much on an objective set of criteria as on cultural conventions about the appropriate forms and contexts of music – ones which those outside this world regarded as uninspiring but which classical musicians could justify both in terms of particular patternings of melody, harmony and thematic structures and by the accepted classifications by music specialists, further authorised by the strongly held image of this music as an artistic heritage coming down in written form from the past. Just what was included changed from time to time, and the whole concept of classical music was certainly fuzzy at the edges; what was clear was that it was based not just on musicological content but on definitions and validations by particular groups of people.

This socially defined canon of classical music was what present-day musicians largely worked with. A few themselves composed, but in general their central responsibility was the perpetuation of this heritage, teaching others the skills to appreciate it or to realise it in their own playing. They thus transmitted the musical works written by earlier composers and did so in a context in which this was considered a high, indeed revered, form of artistic expression supported by widely accepted values about high art and (in some cases) direct state patronage. Concerts by nationally and internationally known soloists and orchestras and by varying combinations of professional players, both live and broadcast, epitomised what most people envisaged as the classical music tradition of this country, backed up by the system of specialised music training, national music colleges and professional musicians.

These activities by elite musicians perpetuating the musical heritage of the past in public concerts made up the most visible manifestation of classical music. But they did not constitute the whole of the classical musical world as it was realised in practice. Certainly this particular model deeply influenced even those on the face of it far removed from the specialist performances of highly qualified professionals. But, as will be clear, there was also a whole grass-roots sub-structure of local classical music. Though perhaps ‘invisible’ to most scholars, in practice this was the essential local manifestation of the national music system, and also (as emerged in chapter 2) both interacted with it and formed its foundation. One aspect was the provision of audiences with the necessary skills of appreciation for professionals coming to give concerts locally, but it extended far beyond this to the whole system of local training, playing, actively practising musical groups and public performances by local musicians.

This ideal classical model was a powerful one which, however vague at the edges, implicitly moulded people’s views of music and of their own participation in it at the local level. They were taking part, it was assumed, in a high art form validated by an authorised historical tradition and a structure of professional specialisation in which experts had to undergo rigorously assessed training ultimately controlled by the highest members of the profession. Of course not everyone who went to a classical concert, learnt the piano or played the violin in a local orchestra had formulated this explicitly or expected his or her own performance to measure up to the highest level of this ideal. Nevertheless, the model had a profound influence throughout the musical groups and activities that were widely seen as part of the world of classical music.

The local awareness of links with the wider classical world and its authorised canon from the past came out in many contexts. One concrete form was the printed scores and music ‘parts’ which were a necessary channel for transmission and performance among local classical groups, both instrumental and vocal. These were often borrowed rather than bought and when a local choir, say, found itself, as so often, singing from old and well-marked copies, it was easy to picture the earlier choirs 20, 30, even 50 years ago singing from the self-same copies – and repertoire – of classical choral music in the days when, perhaps, those parts cost just one penny. Local performers could also regard themselves as the amateur counterparts of the specialist professionals, their reflection at the local level, playing however imperfectly from the same classical canon. It was this pervasive model of the lengthy and highly valued classical tradition which ultimately set the definitions of the musical activities in which local amateurs were engaged.

Amidst these many locally based classical musical activities, what kind of people were the main participants? Is the prevalent assumption justified that classical music is primarily a ‘middle-class pursuit’ or confined to the ‘elite’ rather than the ‘common people’? Judging by Milton Keynes there was certainly one sense in which this was true: if one focusses primarily on highly trained specialist musicians and the national institutions in which they participate, this is almost by definition an elite and select world; and insofar as this model influenced people’s interpretations, classical music was indeed pictured as, in its fullest and best form, a high-art pursuit for the few. But, as becomes clear by examining the local situation, the actual practice which upholds and perpetuates the classical music world consists of more than just these elite musicians. The local amateurs and small-scale events also play an essential part. In their case it is by no means so evident that an elite or a ‘middle class’ label is correct. Indeed my main conclusion – however banal – was that local musicians and participants in local musical activities varied enormously in terms of educational qualifications, specialist expertise, occupation, wealth and general ethos.

Some musical groups did approach more nearly than others to the ideal of the expert professionals in terms of specialist musical qualifications, and this often – though not always – went along with the kinds of jobs or backgrounds loosely referred to as middle class. The leading amateur orchestra, the Sherwood Sinfonia, was a good example. Players had gone through the formal examinations of the national music institutions, and there was a high proportion of local music teachers and of individuals in high-status occupations among their members. But even here there were exceptions, like the young sausage-maker, later music shop assistant, who besides being a Sherwood Sinfonia violinist was a keyboard player and composer with a local rock group, or pupils from local comprehensive schools not all in the ‘best’ areas. The amateur and widely based emphasis within English music was particularly noticeable in the choirs, with their long tradition of extensive local participation without formalised musical expertise or selective background. It was true that the older pattern of local choral societies made up of a cross-section from one locality was – with the change in transport arrangements perhaps – being replaced in the 1980s by choirs recruited on a city-wide rather than neighbourhood basis; but both local ties and a wide mix of backgrounds were still evident in the church and school choirs (see chapters 15 and 16). In such cases generalisation about classical music practitioners coming from just one social background or set of occupations does not stand up: many (though not all) choirs were very mixed.

The same applied to instrumental players, despite the elite nature of some smaller ensembles. Piano and organ playing were widespread, sometimes still learnt on a self-taught basis (especially in church contexts), and even instrumental groups were not all highly select. The Wolverton Light Orchestra, for example, went back far into the local history of Wolverton, the town long dominated by the local railway works. It was first founded as the Frank Brooks Orchestra after the First World War by a bandmaster of the Bucks. Volunteers who also conducted the local brass band, and was later renamed the Wolverton Orchestral Society. Between the wars it played light music with a First World War flavour, the thirty or so players giving regular winter concerts in local cinemas. It was revived after the Second World War, but later took the title Wolverton Light Orchestra to make clear that in contrast to the newly founded Sherwood Sinfonia their policy was to play smaller-scale works rather than symphonies. This they were still doing very effectively in the 1980s, giving six or seven concerts a year, mainly around the Wolverton area, with a playing membership of about thirty. By then there was a fair proportion of local schoolteachers in the orchestra, but over the years – and to some extent still – it had been strongly rooted in the local community and still had a mainly self-taught conductor from the local railway works. It would be hard to regard this as a select elite or middle-class activity in the sense often attached to those terms.

All in all, the picture was a varied one. The high-culture model of classical music should not lead us to conclude without further question that the musicians who in practice made up the classical music world at the local level were themselves members of some clear elite or drawn predominantly from some single class. For Milton Keynes, at least, the evidence points to a weighting towards teachers and fairly high-status occupations in several of the more aspiring instrumental groups, but otherwise – and particularly in the choirs – great heterogeneity of background, education and occupation.

The power of the specialist model, then, which focusses attention on professional concerts and national performing organisations, should not be allowed to obscure the equally real practices of local performance, training and appreciation. This classical ideal – misleading though it can be – is nevertheless of great relevance for the local scene. It provides a framework for the local practice, and without it one justification and measure for the many local orchestras, choirs and instrumental ensembles would be lacking. The recognised tradition of the classical repertoire and the currently accepted styles of presentation also provide local groups with a rationale which they both draw on and help to perpetuate. All in all the over-arching classical music model on the one hand and the local performers and enactors of the tradition on the other interact together in a complex and varied way to transmit and sustain, carry and form, the national and enduring world of classical music so characteristic of this country as a whole and so richly practised at the local level