Читать книгу The Hidden Musicians - Ruth Finnegan - Страница 19

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление5

The brass band world

Given the well-known association of brass bands with the North, the strength and continuity of the local brass band tradition came as something of a surprise. For there were five to eight main brass bands in and around Milton Keynes in the early 1980s (the exact numbers depending on just where one draws the boundaries): the Wolverton Town and British Rail Band, the Woburn Sands Band, and the Bradwell Band (all going back many decades), and the more recent Stantonbury Brass, the re-formed Bletchley Band and (from 1984) the Broseley Brass; also regarded as in a sense local were the century-old Great Horwood Band and the Heath and Reach Band, in villages about five miles from the city boundary. There were also youth bands, bands connected with the Boys’ Brigades and similar groups, and Salvation Army bands in Bletchley and Bradwell. Brass band gatherings like the Bletchley spring festivals had been a local tradition for some time, and were currently concentrated in two annual events, with 50 or so brass bands coming from all over the country to the February ‘entertainment contest’, and a massed concert by local bands every autumn.1

The main bands contained 15 to 30 amateur players each, fluctuating according to the fortunes of the band at any one time, the regulation ‘competition band’ being 25 plus conductor. Their instruments were the standard brass combination of cornets, trombones, baritone and tenor horns, euphoniums, Bþ and Eþ basses, and percussion, played by members of many different ages and, in most of the bands, of both sexes. They made frequent public appearances (far more often than the choirs and orchestras) – highly visible performances, because of the loudness of brass instruments, the tradition of playing in the open, and their distinctive uniforms.

Brass band players were exceptionally articulate about their traditions; ‘it’s a world on its own’, I was constantly told, ‘a whole world’. Among all the musical spheres in Milton Keynes, it was the brass bands and their players that most emphatically made up a self-conscious ‘world’ with its own specific and separate traditions.

This perception was partly moulded by the popular publications about brass bands, the activities of national brass associations and the strong if unwritten traditions that have grown up round brass bands since the last century. This too was how outsiders often regarded them. The image was of bands as essentially working class, following their own autonomous musical style and repertoire separate from the elitist high culture, and composed of (male) players who were either self-taught or had learnt within the family or the band itself. In the past, so went the tradition, it was the heavy manual workers like miners who formed the brass bands: their work-hardened hands could not cope with stringed instruments, but they had one sensitive part left to them – their mouths and tongues. The brass bands were also assumed to be closely linked to their local community, which they supported both through local performances and through carrying the band’s name forward in the glamorous brass competitions.

Band members in Milton Keynes were well aware – indeed proud – of this long brass band tradition which itself shaped their understanding of present-day activities, as well as influencing their repertoire and mode of performance. What is more, several of the brass bands in the area did indeed date back to the turn of the century or earlier, a continuity which added to their sense of historic tradition. The Wolverton Town and British Rail Band was started in 1908 and had even earlier antecedents, the Great Horwood Band was formed in the 1880s, and the Woburn Sands Band in 1867 (though it had lapsed for many years until its refounding in 1957), while the Bradwell Band dated its foundation precisely to 15 January 1901, since when it had had a continuous existence as the Bradwell Silver Prize Band, Bradwell United Prize Band, United Brass Band, then Bradwell Silver Band. Even the younger Boys’ Brigade Bugle Band in Bletchley had continued without break since 1928, while the Heath and Reach Band was approaching its fiftieth anniversary. Others, like the old Bletchley Brass Band or the Newport Pagnell Town Band, had not survived but still left their traces in personal memories and in the music stamped with their name now used by other local bands. Inherited band resources like instruments inscribed with earlier players’ names or the music library, as well as memories of glorious exploits in competition or of contacts with leading local families, also brought home the length of tradition. Some bands had documentary records going back fifty years or more, with newspaper cuttings recording their festivities and successes; these often documented the strong family tradition characteristic of brass bands, fathers being followed over the generations by sons, grandsons and nephews. No other named local musical groups (with the possible exception of a few church choirs) had as long a continuous existence, so that though there had been both demises and new foundings, brass band members were in fact correct to see their tradition as a long-established and vigorous one.

Awareness of their proud history thus played a part in local activities, and to some extent this continuity was striking. The tradition of informal learning was also still influential, and there were still many family links and loyalties within the bands. The competition world was sometimes another continuing context for performances and aspirations, while the tradition of service to ‘the community’ and appearances at local events remained a valued one, and at least some players still spoke of the ideal of bands as essentially made up of ‘ordinary working lads’.

This traditional image of the ‘brass band movement’ was thus of real relevance, influencing repertoire, mode of training, self-image and family and community links. However, as even some players themselves admitted, the picture was also changing, and local brass band practice often did not fit with the traditional image.

For one thing the playing of brass instruments was becoming more assimilated to the ‘classical’ music model, and the modes of learning and performance were changing. Brass instruments were energetically taught in the schools by peripatetic teachers on the same basis as other classical instruments, supplementing the bands’ own youth training schemes and informal teaching. Partly as a result, more girls were learning. Milton Keynes brass bands included female players, and in some of the younger bands girls were actually in the majority – very different from the past. New groups were founded which, unlike the older bands, drew their models not just from inherited tradition but from televised performances and classical instrumentalists.

Brass bands were also part of the high-profile cultural developments promoted by the MKDC. One of the first ensembles off the ground in the show-piece Stantonbury Education Campus was Stantonbury Brass, a youth band run by the Stantonbury Music Centre – an effective choice given the shorter lead time for training up a viable brass than string group. This successful young band was invited to perform at MKDC and BMK-sponsored events and to represent Milton Keynes abroad. Again, the Milton Keynes brass band festival, though building on established local bands, was directly encouraged by the new city’s administration (which happened to include some influential brass enthusiasts). For many, therefore, brass bands were not a separate world of lower-class or ‘popular’ as against ‘high’ culture, but a recognised part of official cultural events in the city. The links with classical music were also increasingly accepted by players and audiences generally, not just because of school brass teaching but through the widely watched BBC ‘Young Musician of the Year’ competition, in which brass instrumentalists always formed one section. One recent winner was claimed as a ‘local boy’ (he came from Bedford and had played as soloist with local brass bands); this added new prestige to brass band playing, and the number of children (or rather parents) interested in brass lessons immediately jumped. There was thus contact between brass band and the classical music worlds, with some overlapping membership between brass bands and classical ensembles (like the Woburn Sands Band and the Sherwood Sinfonia).2

Another way the older image no longer really applied was in band membership. The ‘working-class’ picture may have influenced people’s perceptions, but by the 1980s hardly fitted the Milton Keynes bands. The new bands (the Bletchley Band and the Stantonbury Brass) were mostly young people of very mixed backgrounds, many still at school, and had girl players as well as boys; and even the older bands included a fair mix. This, furthermore, was how at least some bands in practice saw themselves, even if they also relished the nostalgic flavour of the earlier image. One long-established band, I was told by its secretary, included political commitments ‘across the whole spectrum’ and a cross-section typical of local brass bands generally: postmen, teachers, telephone engineers, a motor mechanic, personnel manager, master butcher, university teacher, train driver, and schoolchildren from state and independent schools. Another band (partially overlapping in membership with the first) was less varied, with a larger proportion of jobs like clerk, labourer, storeman, or shopworker, but also including computer engineers, a building inspector, a midwife and several schoolchildren; as their musical director summed it up, ‘the old cloth cap and horny hand image is dying out’.

The bands also contained players who had learnt their craft in several different modes. Some had indeed learnt in the traditional way from brass players within their own families or bands, then perfecting their skill through actual band playing. Others had been taught in the formal classical mode which stressed reading music and being able to play in classical music ensembles. Others had combined the two. This mixed experience did not seem to undermine the communal loyalty of the bands, and was indeed exploited by the bands, who used a variety of methods in their own youth sections. But it was yet another way in which the model of one homogeneous brass band tradition was being modified in the light of actual practice.

The day-to-day commitment of players to their band was apparently as strong as ever. The common pattern was of one or, more often, two weekly practices of several hours-two weekday evenings or one plus a weekend meeting. Some bands ran training sections on yet another evening, when experienced players joined in teaching the younger members.

Despite the strong family and personal link in local brass bands, the organisation was quite formal, on the ‘voluntary association’ pattern so common in English society. Bands were formally constituted, had the same kind of committee structure as choirs and orchestras, functioned on the basis of membership fees and audited accounts, and held an Annual General Meeting with formally conducted proceedings. They were also hierarchically organised under a permanent conductor (sometimes with assistant) who directed the practices and the public performances, assisted by a committee. Unlike some earlier brass bands they were not sponsored (apart from the launch money for the new Broseley Brass) and with the partial exception of the Wolverton Town and British Rail Band, who still held meetings in the British Rail Engineering canteen, they were not attached to particular works, but supported themselves as independent bands from their own contributions.

A great deal of authority lay with the conductor (sometimes entitled musical director), backed up by the committee. The Bradwell Band constitution, redrawn in 1978, stated that the conductor or his deputy had full control of band personnel during engagements with the right to report any irregularity to the committee, who would ‘deal with the offending playing member’. Similarly he was to report any playing member frequently absent from practices or performances without his permission (a more stringent rule than for many other types of local musical group), and in general ‘when in uniform, playing members must uphold the dignity of the Band at all times, and engage in no activity that would bring the Band, Trustees and Patrons into disrepute. The conductor shall refer to the committee any breach of this rule by any member.’ The actual conduct of affairs is of course often less formalised than constitutions suggest, and an atmosphere of camaraderie and enjoyment was one noticeable characteristic of local brass bands. Nevertheless there was also a definite air of authority at band events, and practices were hierarchically directed sessions when people worked at the conductor’s bidding in a highly disciplined setting which players felt strongly obligated to attend.

In addition to routine practices, the bands all took on performing commitments, especially in the summer and at Christmas (see below). Some also competed, and new local and regional competitions had been developing which several local bands entered. The Woburn Sands Band, for example, after being out of the competition world for a time, had begun competing again about ten years before and was advancing up the national grading system. Stantonbury Brass and the Bletchley Band also entered competitions regionally and the new Broseley Brass were already having success. Other bands concentrated more on local appearances, but the tradition of competitiveness was still a powerful one even for currently noncontesting bands, coupled with an awareness of the distinctiveness and pride of each separate band.

The competition world also had its own rituals. This made heavy demands on band members, for it meant not only playing at as high a standard as they could possibly achieve, but also the necessary travel and assessment of their own and other performances. The sense of occasion in these highly structured and intensive competitions had much to do with the enthusiasm of brass band players both for the ‘brass band movement’ as a whole and for their strong identification with their own bands.

Competitions were not the only occasions for band loyalty and sense of performance. Local brass bands had an accepted obligation to play at local events and in the community that they regarded as, in some sense, ‘their own’. Local fêtes, carnivals, outdoor carol services, charity occasions, the big events at Christmas and the Remembrance Day rituals all regularly involved appearances by one or another of the local bands.

Indeed at some times of the year, they had little respite from playing. Take, for example, the Bradwell Band’s 1980 Christmas events as listed in the local newspaper’s notice (not their only Christmas engagements): Thursday 18 December, Eaglestone Hospital, 7.0 p.m.; Sunday 21st, The Green, Newport, 10.30 a.m.; Monday 22nd, New Bradwell streets, 7.0 p.m.; Tuesday 23rd, Bradville streets, 7.0 p.m.; Wednesday 24th, New Bradwell streets, 7.0 p.m.; Christmas morning, New Bradwell streets, 6.0 a.m. Their very similar programme in the Christmas season in 1982 (out ‘carolling’ every day from 11–25 December inclusive) followed a long tradition in the area culminating in the famous ‘Christians Awake’ at six on Christmas morning in New Bradwell, a tradition which had not been broken for well over fifty years. It caused amusement as well as pleasure – who really wanted to be woken up or out at that time in the dark and freezing cold? – but was close to the hearts of band and New Bradwell residents alike, and players spoke warmly of going out before dawn, being greeted with drinks or gifts or, by the children, friendly abuse, and finding glasses of whisky waiting on the best doorsteps. Similarly, the Woburn Sands Band year’s events in 1982 covered over twenty performances – at local brass band festivals in February and October, the Regional Round of the National Brass Band Championship in March, then the Finals in London in October, local concerts in April and May, appearances at a dozen fêtes, carnivals, fairs and shows in local towns and villages throughout the summer, hymn-singing under the tree at Simpson village in July, Remembrance Day ceremonies in November, and OAP and Women’s Institute parties in December; in addition nearly three weeks in December were committed to carolling around the local areas.

Given the intensity of such commitments on top of the regular band practices which timetabled their weekly activities throughout the year, it is not surprising that players spoke of the band ‘taking over their whole lives’, with consequences for all their other obligations; but they added that this was well compensated for by the ‘good humour and fun’ of band life. For some, brass playing took a dominant role in planning their lives; at least one player had settled in a particular village because of its band. For others, band commitments had become almost ‘like a job’ – except that they felt less guilty taking a holiday from their paid employment than from the band – and a high proportion of their ‘free’ time was taken up by band obligations: performing and practising, travelling, organising uniforms and music, fundraising, or preparing and transporting instruments.

The band could be a source of more than just musical co-operation, for several bands had associated groups, and performed social as well as musical functions. The Wolverton Town and British Rail Band had a Ladies Supporters Club which met once a month at the BR Canteen at Wolverton to raise money for the band, while the Woburn Sands Band had its own madrigal society led by a horn player who was also a singer; members met in turn at each other’s houses after Sunday morning band practice. Bands took some social responsibility for their members, marking events like weddings, deaths, departures, successes, and also sometimes co-operating in baby sitting, arranging transport, and other less directly band-related exchanges such as sharing skills or information.

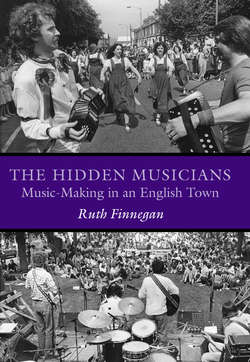

Participating in a brass band was more than just ‘going along for a blow’. Quite apart from the intensity of the musical commitment, band members – and above all the organising committee – inevitably became involved in a host of social and financial arrangements. Some of these practical aspects are explored further in part 4, but for brass bands particularly there was the heavy cost of instruments and uniforms and the importance of the music library. Brass instruments were not cheap, especially the larger ones, and brass players might find themselves using instruments worth £600, £1,000, £2,000 or more. Bands sometimes undertook to lend out instruments to players, a heavy drain on their resources, for £1,000 or more might have to be expended annually on purchases and repairs with all the fund-raising and background work that entailed. Uniforms too were expensive, and fitting out a band with a new uniform at the cost of many hundreds of pounds often had to be paid for through local fund-raising events and gifts – another way in which a band was bound into the locality in which it both played and raised money. Local people helped the Wolverton Town and British Rail Band to raise £3,000 for thirty-three new uniforms in 1981, for example, and were thanked by a free charity concert. The result was a highly visible group, clearly marked out by their military-style costume, clearly distinguished from other groups in the area (see figure 10).

The music library was an important band possession. This contained the multiple music parts played by the band and its predecessors, a mark not only of tradition through time but, as the players themselves put it, a ‘priceless’ resource for them. Of course bands experimented from time to time with ‘newer’ music, but given the availability of their own library of the classic band repertoire there were economic as well as sentimental reasons for bands to make good use of the (literally) well-worn music that had come down to them. This was yet another sign of their unity as one named band, and (together with their other heavy investment in instruments and uniform) one factor in the long life of brass bands compared to other musical groupings.

Figure 10 The eighty-year-old Wolverton Town and British Rail Band. The current members pose in their band uniform

Most bands were also bound by additional links of kinship and friendship. The local brass bands seemed to be full of relatives – at first sight, quite remarkably so until one recalls the common tendency for music in general and brass banding in particular to run in families and the long history of many of the local bands. It was common for several members of one family to play in a band, both within and across the generations, made easier by the lack of interest in age so long as members could play (in local bands the age range was from 9 to 70). Playing together forged intense relationships and provided a sphere in which more links could be formed which in turn bound the members together yet further. This was especially so in the longer-established bands, but it also extended to the more recent ones, some of which had been helped by friends or relatives in the others (the Bletchley Band, for example, was founded by players from the Woburn Sands Band and the Bradwell Band). These links were not always and in every respect harmonious, of course – but this was perhaps all the more evidence of the bands’ close-knit quasi-family nature.

It was not just the number of hours, social ties or amount of trouble that for participants constituted their affiliation to the brass band world, but the qualitative experience and the meaning this held for them. They were creating and transmitting music known to be part of the brass band repertoire, music coming down to them from the past as visibly enshrined in their own library and store of instruments or, if embarking on innovative ventures, doing this within the traditional brass conventions and in this sense making it their own. They were engaged in the joint act of making and receiving music in a known and valued tradition with its evocative visual as well as acoustic associations: the glittering polished instruments, band insignia, proud display of uniforms, and quasi-military and tradition-hallowed bearing.

Figure 11 An informal photograph of the Woburn Sands Band shortly after competing in the National Brass Band Finals, showing the age range typical of many music groups (here 11 to 70)

The music above all was central, with its burst of sound filling the surroundings, arising from not just hours but years of skilled work and enacted by two dozen or so people participating as both individuals and a collectivity in a context in which age and background were of no account for ‘you’re pursuing an activity and in pursuit of that activity one loses oneself’. Building on their hours of practice, they were taking part in a performance to the highest standard the band could produce, an event unique to them yet tradition-drenched, of both public acclaim and rich aesthetic meaning. Small wonder that one player summed up banding as ‘a way of life’ which, despite the grumbles, ‘I wouldn’t be without’.

This sense of belonging to an integrated distinctive world, the inheritors of a proud and independent tradition, was further enhanced by the continuation of the long tradition of brass bands performing a public function for the local community. Of course such a statement needs qualification. What was seen as ‘local’ or ‘the community’ varied according to the speaker(s), the situation, even the time of year. And in some respects brass bands were just like any other musical groups performing in and around their own local base at both small and large events, not necessarily admired by or (probably unlike nineteenth-century bands) even known to all the local residents. What was striking, however, was the explicit ideology that brass bands had a direct relationship to their ‘own’ locality. The band was expected to turn out on ‘public’ occasions and to play a part in rituals of the musical, religious and official year, while in return members of the locality should support them not only in musical events but also in fundraising, particularly in street donations to band funds during the ‘Christmas carolling’. The local band’s public appearances at Christmas festivities, local carnivals and shows, ceremonies like the public opening of some new institution, or (as representatives of their own locality) in competitions or visits outside were seen as a necessary part of such events and an expected function of the band. The sense of let-down when there was once a mix-up and the local brass band did not play at the local Remembrance Day brought home the importance many people attached to this function – even those who did not particularly like brass band music.

One of the images associated with local brass bands in the 1980s (as earlier) was of a group performing an integrating and public role for their locality. Even though by the 1980s band players did not necessarily live in the immediate neighbourhood at all, local brass bands could still see themselves as somehow representing and enhancing the whole ‘community’ at public events – whatever that ‘community’ might be in different circumstances: the local village for the Woburn Sands Band; the town of Wolverton and its workers for the Wolverton Town and British Rail Band; or, in some situations, the whole developing new city of Milton Keynes. This aspect was no doubt facilitated by the ability of brass bands to perform so visibly and audibly in the open air, but even so it was remarkable that a musical tradition which was also seen as separate from others and was certainly not to everyone’s taste should nevertheless have been accepted as being some how ‘above the battle’ and, despite its basis in the world of privately organised voluntary associations, as providing mutually beneficial support for the large ‘community’ occasions.

Up to a point, just about all the voluntary musical groups performed something of this public function, but it was in the case of brass bands that this idea was most prominent. Brass bands both constituted a quite explicitly perceived ‘world of their own’ and, at the same time, were called on most directly of all the groups considered here to support the public celebrations of the communities in which they practised.