Читать книгу The Hidden Musicians - Ruth Finnegan - Страница 21

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление7

The world of musical theatre

There was a strong operatic and pantomime tradition in Milton Keynes, stemming from the older towns on to which the city was grafted. The Bletchley and Fenny Stratford Amateur Operatic Society was already putting on Gilbert and Sullivan operas before the First World War, a tradition which continued for many years (Wright et al. 1979, Pacey n.d.), while Newport Pagnell had a Gilbert and Sullivan Society at the turn of the century. Local schools too had long put on musical plays. Among them were the long-remembered Bletchley Road School productions of The Rajah of Rajahpore and The Bandolero between the wars, the latter to audiences of all the local celebrities and raising the then record sum of £128 (Wright et al. 1979).

This tradition was still very much alive in the 1980s, partly overlapping with classical music, but separate both organisationally and to some extent in personnel. It included a wide range of musical categories – light opera and operetta, musical plays and comedies, ‘musicals’, pantomimes and some music hall singing – all sharing the property of being presented through dramatic enactment on stage, often accompanied by the theatrical appurtenances of costume, make-up, lighting, and carefully produced dramatic ‘spectacle’. The activities of those engaged in this well-established form of musical expression were not just separate one-off efforts but related together and organised within its own world of musical theatre. Within Milton Keynes this found expression in a flourishing amateur operatic society which had been putting on regular performances for a generation or more, as well as two active Gilbert and Sullivan societies, and musical plays and pantomimes were a constant feature of school and community group activities, above all at Christmas.

The continuing strength and attraction of the local operatic tradition can be illustrated from the Bletchley (later Milton Keynes) Amateur Operatic Society. This was started in 1952 by a local Bletchley businessman who got a few of his local and church friends together, saying how much he loved the music of Lilac Time and couldn’t they have a go at it? He succeeded in his persuasions, and Lilac Time was soon followed by The Maid of the Mountains and Quaker Girl.

From then on the society snowballed, drawing in not only local businessmen in Bletchley but enthusiastic participants from all backgrounds: teachers, bricklayers, electricians, secretaries, self-employed plumbers, housewives and professionals of various kinds; and it had close links to local churches. The list of patrons numbered many local notables, both those from the traditional land-owning families and, increasingly, public figures from local government or – like Dorian Williams – of national fame, and there was always financial and moral support from the local business community with whom the ‘Amateur Operatic’ had consistently beneficial links. The founder, Ray Holdom, was musical director for many years, and besides his musical leadership also used his business contacts in television maintenance to interest yet more potential members in Bletchley and, from the mid or late 1970s, in Milton Keynes as a whole. By the 1970s and early 1980s, the Milton Keynes Amateur Operatic Society was thus one of the most successful local societies with a very active membership of around 100, backed up by many part-time supporters and regularly enthusiastic audiences.

The centre of its activities was still, as from the beginning, its large-scale annual production in Bletchley. Over the years, these had included (among others) Lilac Time, The Count of Luxembourg, My Fair Lady, Orpheus in the Underworld, Blossom Time, The Sound of Music, White Horse Inn, Waltz without End, Rose Marie, The Student Prince, Free as Air, The Gypsy Baron, South Pacific, Pink Champagne, Carousel, Half a Sixpence, Summer Song, The Pajama Game, and The Merry Widow, some more than once. These annual productions were grand affairs with a run of five, six or seven performances, complete with London-hired costumes, full-scale stage management, lighting and scene shifting, as well as lavish programmes containing photographs of the main performers and officers, synopsis of the plot, and decorative, often witty, advertisements by local businessmen connected with the society. The cast usually included about 20 principals, a chorus of around 30, a troupe of dancers from one of the local dancing schools, and an orchestra of about 20 local instrumentalists. In addition, of course, as the programme seldom omitted to point out, ‘there have to be two off-stage workers for every one on stage’ (often spouses and friends of the performers), not to speak of three or four rehearsal pianists and both producer and musical director. These productions were acclaimed events in the locality, usually packed out on the later evenings and for many the occasion of an annual family outing. The society also often put on less elaborate ‘variety concerts’ or musical evenings of ‘songs from the shows’, while their week-long Christmas pantomimes were light-hearted affairs, extremely popular with local audiences. Their versions of Aladdin, Dick Whittington, The Sleeping Beauty, Mother Goose and many others were often booked solid well before the holiday, most of them written by Ken Branchette, a local test driver technician who had been a member of the society for twenty-five years.

These amateur operatic events received lavish coverage in the local press, no doubt partly because of their well-connected networks. The local papers often devoted nearly a page of review to the main annual productions, complete with photographs and a full cast list down to the names of every one of the chorus, dancers, orchestral players, scenery painters and builders, and lighting and stage assistants. Such accounts were presented with an air of analytic detachment but overall were extremely laudatory, in practice constituting one expected element in the shared celebration. The whole cast and their admirers could bask in such comments as ‘And what a chorus the society now has!’, ‘The singing of all these principals, both in solo and in combination was a strong feature … there was also considerable strength in the supporting parts’, ‘The speciality dancing … was splendidly done’, ‘And once again the set designing genius and stage manager was Ken Branchette’.

Every year had its high points, but for the Amateur Operatic Society one of the largest occasions was their ‘Silver Jubilee Year’ of 1977, when they celebrated twenty-five years of active existence. A special ‘jubilee committee’ was set up including local businessmen who persuaded many local bodies to sponsor them. They put on a year’s programme of Babes in the Wood in February, Schubert’s Lilac Time in May, a variety show in the autumn and a Grand Finale in Bletchley Leisure Centre in October, with all proceeds going to a local hospital charity: ‘it is felt that after the Society’s 25 successful years in the area the adoption of the principal charity would be a most fitting way of saying “thank you” to the community as a whole for their loyal support during this period’. The year’s events brought great satisfaction to the committee and organisers who recalled how twenty-five years before, the society had started off with many young members: ‘many are still members and still looking young’ and, still with a large number of young members and a supporting list of fifty or so patrons, were already ‘looking forward to their Golden Jubilee in 2003’.

The Silver Jubilee was a specially grand event, but every year involved intensive effort and rehearsal by scores of participants. Preparations and rehearsals went on almost all year for the major annual productions, in a recognised cycle that started off with the enrolment and AGM evening in the autumn, then the start of the weekly or twice-weekly practices. As the time of the main public performances in April or May approached the pace of rehearsing increased. Even during the main part of the year ‘it took over my life’, as one member put it – attending regular rehearsals two nights a week for acting, one for singing and yet another for dancing; near the end this turned into every night of the week and weekends too.

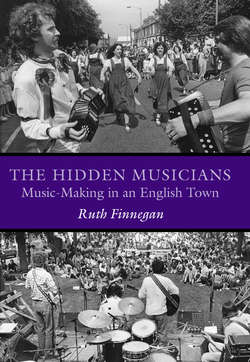

Figure 14 Scene from the Milton Keynes Amateur Operatic Society’s pantomime Babes in the Wood, a sell-out at Stantonbury Theatre in January 1983

As with some other long-established clubs, the Milton Keynes Amateur Operatic Society was by the late 1970s and early 1980s a closely knit social group many of whose members knew each other well, in some cases also linked by kinship, love or marriage. A whole series of social activities as well as their joint musical production drew them together. In the summer and autumn of 1976, for example, during the ‘resting season’ between rehearsals, social occasions included a visit to Foscote Manor (the home of the society’s President, Dorian Williams), provision of stalls at both the Bletchley and Newport Pagnell Carnivals (August), a car ramble (August) and a visit to a local Gilbert and Sullivan Society’s Pirates of Penzance in September. As a long-established and economically stable society, the Amateur Operatic Society was undoubtedly one of the most flourishing local societies, drawing on a wide range of members, well connected with the local business and landed community and raising extensive funds for local causes.

There was more to this than just a financially effective business organisation, though, since for most active participants it was the music that was paramount. Under the guidance of a series of energetic and gifted musical directors, local soloists flourished and even the less skilled chorus and small-part singers expanded, steeped in music for hours on end, attending constant rehearsals, studying their parts in every odd moment they could snatch from work or family – small wonder that one concluded ‘I ate, slept and dreamt music.’ Some members had before had relatively little systematic musical experience, and for them such experience could be a revelation – as for the local plumber unable to read notated music who talked and talked of the joy of singing in operas and pantomimes and his discovery of the beauties of listening to music. For their regular audiences too, the public performances were not only grand occasions of theatrical display, marked by colour, movement, dance and dramatic enactment as well as musical expression, but also an opportunity to hear well-known tunes and arrangements which even after the end of that year’s performance could remain in the memory to evoke that special experience and lay the foundation for looking forward to the next year’s production.

The Amateur Operatic may have been the oldest and best connected of the operatic/dramatic musical societies, but it was not the only one. In the Milton Keynes area, as so widely in Britain, the Gilbert and Sullivan tradition also flourished. The Wolverton and District Gilbert and Sullivan Society was founded in 1974 and was still presenting its grand annual productions of, for example, The Mikado, Patience, The Yeomen of the Guard and The Pirates of Penzance some ten years later under its musical director, the well-known local personality Arnold Jones, who had followed his foreman father into the Wolverton Railway Works early in the century. A similar cycle of rehearsals and productions was also followed by the Bletchley-based Milton Keynes Gilbert and Sullivan Society, an offshoot from the Amateur Operatic Society in 1972. Once again there was a strong link with local churches, and in some cases a tradition of giving smaller-scale concerts during the year for charity.

The drama societies also often had a musical side, like the long-established Bletchco Players, the New City Players, the Longueville Little Theatre Company, the Woughton Theatre Workshop, and various drama groups based on the Stantonbury Campus which had developed a striking series of musical plays based on local history. They produced musical plays and pantomimes from time to time, or co-operated with the operatic groups’ productions by encouraging their own members to participate.

Pantomimes also played an important part in the musical and theatrical year. Most local dramatic societies put one on during the Christmas season, and for some, like the Bletchco Players, the Milton Keynes Amateur Operatic Society, and New City Players, it had become an annual obligation. Other groups who did not aspire to regular musical or theatrical productions also put on pantomimes at Christmas – Women’s Institute branches, for example, church or village groups, and schools. These were especially popular when, as often, they were specially written or adapted to include local and topical references, and built on a long local tradition of amateur Christmas pantomimes directed to ‘family entertainment’. Here again, however unpretentiously the pantomime was produced, a huge amount of work was always involved, not only in the many rehearsals but also in the co-ordination between large numbers of people exhibiting several art forms – dancing, speaking, acting, singing, playing.

One of the striking characteristics of the world of musical theatre was the amount of co-operation between the individuals and groups involved. There were joint occasions, for example, like the charity concert in December 1979 by the Milton Keynes Amateur Operatic Society and the Milton Keynes Gilbert and Sullivan Society. Singers and players from one society would also come along to help in productions by others: Amateur Operatic Society performances, for instance, included actors from the Bletchco Players and singers from the Gilbert and Sullivan Societies. Many of the same soloists appeared in the performances of several different groups during the yearly cycle, even though each society had a core of its ‘own’ leading singers who reappeared year after year, to the delight of the regular audiences.

Because of the complex of arts involved there was also contact with musical groups outside the theatrical world. This was partly due to overlapping membership, for many operatic singers also belonged to church choirs, and players in the accompanying orchestras often played in one or another of the local orchestral or instrumental groups. This could set up conflicts of loyalty, of course, when a musician had concurrent obligations which could not be met simultaneously, a situation that could and did lead to friction; alternatively it could be avoided by careful planning, as with the Wolverton and District Gilbert and Sullivan Society, which had extra rehearsals in the summer because the Wolverton Light Orchestra, which shared the same conductor and (in some cases) members, took a rest then. Other contacts were at a more formal level, as when the Newport Pagnell Singers joined the Stantonbury Drama Group in a production of The Pirates of Penzance. The local dancing schools too regularly co-operated in musical plays and pantomimes, adding a sparkle to the presentation that was much appreciated by local audiences (themselves swelled, of course, by parents and other relations of the dancers).

Besides the societies specifically formed to produce performances of musical theatre, this art form was also popular as one among a number of possible activities by groups such as churches, schools or community social clubs. The example of pantomimes at Christmas has already been mentioned, but the same pattern was also noticeable for many other kinds of musical. Many schools – especially those with younger pupils – liked to have a musical play on a nativity theme as their Christmas production, while both primary and secondary schools sometimes put on musicals as their main annual production. This sometimes led to complications because of copyright difficulties for well-known musicals, so many schools turned to writing their own. Such occasions necessitated a huge amount of effort and enthusiasm by children and staff alike and – though scarcely attaining the professionalism and scale of the Amateur Operatic Society’s productions – still in their own way demanded the same range of theatrical skills on and off the stage. Church social groups too produced musical plays, sometimes composed and written by their own members, and these too could involve the members in many months of work and the need to draw on the varied resources of a wide number of people – not just chorus and actors, but also people to provide the costumes, props, backcloth and stage management generally.

Despite the heavy demands on time and expertise in this particular form of musical expression it still attracted considerable numbers both in societies organised specifically for the purpose and in other groups for whom this form was appealing in itself and popular with their potential audiences. Clearly the ‘finish’ of the various productions throughout the city varied considerably, but they all worked recognisably within the same musical theatrical framework.

The ideal model drew on the expert and lavish productions which were known from visits to professional shows (or to some extent from seeing broadcast or filmed versions), and this informed both the productions of the leading societies and, perhaps through their performances in turn, the smaller-scale events in the schools and other groups. But though this model helped to form the aspirations and expectations of local participants, the local amateur performances were not just imperfect copies of professional productions but made up a world in their own right which both transmitted and, in a sense, constituted the world of operatic and theatrical music for its admirers and executants in Milton Keynes and, no doubt, for many others through parallel institutions elsewhere in Britain.