Читать книгу The Hidden Musicians - Ruth Finnegan - Страница 20

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление6

The folk music world

Active performers of the music known as ‘folk’ were a select minority in Milton Keynes, in contrast to the wider distribution of many other local forms. But for the performers their participation in the folk music world was a source of the greatest satisfaction, often taking up just about the whole of their non-working time and playing a large part in their self-definition. Their numbers were not negligible either. In the Milton Keynes area in the early 1980s, there were at any one time about a dozen ‘folk groups’, four or more ‘ceilidh’ dance bands and five or six ‘folk clubs’, the latter dependent on a pool of local performers. ‘Folk music’ was also heard and danced to by a much wider circle through the established custom of local associations hiring a folk dance band to play for their annual socials.

Understanding the folk music world can best start from some description of the ‘folk clubs’. These were independent clubs with their own clientele and organisation, meeting regularly in local pubs: the Song Loft (earlier the Stony Stratford Folk Club) at the Cock Hotel in Stony Stratford on every other Friday; the Hogsty Folk Club (later the Hogsty Music Club) weekly or fortnightly on Mondays, then Tuesdays, at the Holt, Aspley Guise; Folk-at-the-Stables at WAP, usually monthly on Saturdays (a more professionally oriented club than most, though with an amateur resident band, the Gaberlunzies); the Fox and Hounds Folk Club at Whittlebury (earlier the Whittlebury Folk Club) on the alternate Fridays from the Song Loft; and the slightly different Lowndes Arms Ceilidh Club at Whaddon on the last Thursday of the month, a folk dance club similar to the folk clubs in atmosphere, music, personnel and resident band. It will be clear from the list both that the club network was extensive and that clubs went through different locations, names and timing. This immediately points to one characteristic of local folk clubs – their relative transience under a given title. There were others too, even less long-lasting, which for a time engaged people’s enthusiasm but faded out after a few years or months, among them the Black Horse Folk Club, the Bull and Butcher Singers’ Club, the Cannon Blues and Folk Club, and the Concrete Cow Folk Club; and how the new Merlin’s Roost Folk Music Club would do (founded autumn 1984) still remained to be seen. There were also gatherings on a regular but less formal basis, like the Sunday lunch sing-songs that drew 50–100 people at the Bull Hotel in Stony Stratford, then shifted to the Black Horse at Great Linford, where (as one leading singer put it) ‘anybody’s welcome to join in, play along, sing a song, add some harmony to a chorus, or simply have a beer and listen’.

Amidst all these changes there were always some five or six clubs which devotees could attend. The accepted system was that club meetings were arranged on a periodic cycle, avoiding mutual competition by functioning on different nights throughout the week or month. A real enthusiast could spend almost every night each week at one or other of the nearby clubs.

There were detailed differences between clubs, for, as one experienced performer commented, ‘each club goes its own way, does it how it works for them’; but there were also recognisable patterns. Almost all were associated with a local pub, meeting weekly or fortnightly in its ‘special function’ room. They were open to casual visitors, but also normally had membership subscriptions, and the entrance fee of around £1.00–£1.50 was lower for members. Around 40–70 typically came on any one night, roughly half men and half women, with 120 or 150 for a well-known artist. Clubs usually ran both ‘singers’ nights’, at which the club members provided free entertainment, and evenings with visiting ‘guests’. The visitors were paid a fee, the amount varying according to reputation and distance: a local musician might get £10–£20, a well-known non-local artist up to £100. The balance between singers’ and visitors’ nights partly depended on club size (and hence funds). A well-off club aimed to have three or four guest nights to one ‘singers’ night’, but this was not always easy since even with an entrance charge of £1.50 the room (and audience) might not be big enough to recoup the cost of an expensive guest.

An evening session involved a high level of participation from those present, and even where there were invited performers local members often performed too as ‘floor singers’. The general atmosphere was relaxed, with people sitting around tables drinking as they listened or joined in the songs, but there were elements of formality too. Starting and finishing times were fairly strictly kept to, there were accepted conventions about introducing and applauding performers, and the organisers tried to stop too much moving around during the performance of a song – in contrast to some other musical performances in pubs. Since finance was always a problem the evening often included a fund-raising raffle, sometimes with a recording by the visiting performer as the prize.

The clubs were run by local organisers and committees (with the partial exception of the Folk-at-the-Stables, backed by the professional organisation of WAP – though even there the artistic side was organised by a local teacher and folk musician). The work involved was extensive – arranging with the local pub, booking guests, ensuring a supply of floor singers, organising publicity, and entertaining visiting artists. Above all the organisers had to worry about funding – and for most folk clubs this was precarious. True, a certain amount came in from club fees, entrance charges, and raffles, but against this there were the constant expenses: rent of the hall, publicity, entertaining, and guest artists’ fees. Most clubs just could not afford high fees. This was probably one reason why they had few professional artists – in the sense, that is, of full-time musicians; for in the other sense of accepted standards many folk performers were regarded as ‘professional’, combining full-time jobs with regular appearances in the clubs. The fees remained low from the performers’ viewpoint, but clubs still found it hard to make ends meet and for this reason local guests often agreed to take minimal fees or to perform ‘free’. They might still be entertained to food and drinks, and a token of, say, £10 might be pressed on them in the form of a gift. The organisers usually found they were ‘dipping into their own pockets’ for stamps, phone calls, petrol, entertaining guests, providing the tickets or prizes for the raffle, having visiting artists to stay or just putting money ‘into the kitty’. Regular members too joined in, not least through the pressure to make generous contributions via the fund-raising raffles. Given these constraints, it is scarcely surprising that some clubs were ephemeral, rather that there were always some folk clubs flourishing, several having lasted for years.

Folk clubs were to be found not only in the immediate area, but also in a circle around it. There were folk clubs at, for example, Nether Heyford, Daventry, Aylesbury, Luton and Dunstable, all on occasion patronised by Milton Keynes residents. How far people were prepared to travel depended on both commitment and mode of transport (most in fact had access to cars). Some devotees spent just about every night of the week at some folk club or other in what they classified as the vicinity, up to twenty-five miles or so away. One husband-and-wife pair, for example, keen folk enthusiasts and performers, regularly spent their evenings (after work) as follows: Sundays, Daventry Folk Club (the oldest in the area, going since 1965); Mondays, Hogsty Folk Club, Aspley Guise; Tuesdays, either the Nether Heyford Club or the Black Horse Folk Club at Great Linford; Wednesdays and Thursdays, ‘not so good because people had no money’, but sometimes playing at home; Fridays, alternately the Cock at Stony Stratford or the Whittlebury Folk Club; Saturdays, Folk-at-the-Stables, Wavendon. This weekly cycle was not unique. Another example, typical of several, was someone in a demanding, full-time job who nevertheless ‘lived for folk’: Sundays, Daventry; Mondays, Hogsty; Tuesdays, Old Sun Folk Club at Nether Heyford; Wednesdays, teaching German (his one non-folk evening); Thursdays, practising; Fridays, the Cock, Stony Stratford or Whittlebury; Saturdays, live performance locally or further afield.

There was also the wider network of folk clubs that had been growing up throughout the country from the late 1950s, each with their own local cycles. Folk enthusiasts who had to travel to other parts of the UK could (and did) consult the English Folk Dance and Song Society directory of clubs and made a point of attending them. As one much-travelled folk participant put it, ‘they’re all the same – and, different. You can go into any and know they’ll be friendly.’ Women might feel self-conscious in a strange pub, but in a folk club ‘you feel quite comfortable’. It was accepted form to walk into an unfamiliar club anywhere, perhaps asking ‘Any chance to sing?’ or perhaps waiting to be persuaded the first time, but then recognised in later visits; names and personal contacts were not needed, for the system was open and familiar. One experienced folk attender summed it up: ‘you just feel at home straight away – a home from home’.

The folk club world was thus country-wide, and in contrast to some other forms of music the national network of clubs was known and accessible to all enthusiasts. This wide perspective among folk music devotees also came out in the regional or national folk festivals, and Loughborough, Reading, Norwich and Cambridge were among large folk events attended by local enthusiasts and performers. Folk news-sheets (like Shire Folk and Unicorn) were also springing up in certain regions, and these too encouraged wider awareness of the folk music world, as did the English Folk Dance and Song Society and Perform (a national society to encourage live music, with strong links to the Milton Keynes folk world), and the established practice of folk performers circulating as guest artists among folk clubs and festivals up and down the country. For Milton Keynes dwellers their local clubs were what they were most regularly involved in, but they were also very aware of the country-wide ‘folk world’ of which they were a part.

Many of those who attended the folk clubs went as receptive and participating audience or provided ‘floor’ performance from time to time. The clubs also thus rested on a pool of informal local talent in the form of floor singers or instrumentalists and – not least – chorus participants, apparently so readily available in Milton Keynes folk settings. But there were also the actively performing groups, together with a few individuals who themselves travelled the ‘folk club circuit’. Of these categories, the most important locally were the bands, for though some well-known performers (like Matt Armour or Beryl Marriott) lived locally, they made relatively few local solo appearances and even then mostly performed in virtue of their membership of a local band or club.

In the early 1980s, there were about a dozen folk bands of one kind or another in and around Milton Keynes. Some were ephemeral, but all had put on at least some performances. They included the Cock and Bull Band (mixed amateur and professional); the Boodlum Jug Stompers; the Hogstymen; the Hole in the Head Gang; Merlin’s Isle; Pennyroyal; the Whittlebury Residents; the Green Grass Band; Streets Ahead (folk rock); Threepenny Bit (a school group); the short-lived and part classical England’s Lane; and various school and church groups. In addition there were the barn dance or ‘ceilidh’ bands: Music Folk; the Gaberlunzies (and its stretched version, the Gaberlunzies Elastic Band); the Banana Barn Dance Band; and Sunday Suits and Muddy Boots.

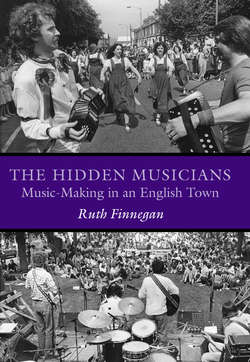

These bands performed in the local folk clubs just described, and for local fêtes, weddings or dances. Some also appeared on an occasional or regular basis at pubs and social clubs. Outdoor events and local folk festivals were also popular occasions for performance. Some of these, like the Cock and Bull Festival, were short-lived only, but there were also annual events like the one-day Black Horse Folk Festival. The largest regular gathering was the ‘Folk on the Green’ festival in Stony Stratford (figure 12). This had taken place yearly in June since 1973 and by the early 1980s was attracting 2,000–3,000 people a time, having become accepted, as a local newspaper rightly expressed it, ‘as one of the great family events of the year, now an established tradition’. It was the brain-child of a local primary teacher and a low-cost event dependent on local performers rather than imported professionals. The 1982 ‘Folk on the Green’, for example, included seven named local artists performing as individuals, plus the local groups Pennyroyal, the Hole in the Head Gang, the Stony Stratford Morris Men, Old Mother Redcaps and Mentil and the Lentils, and other years followed the same pattern – a magnificent show-piece of local folk talent.

The dance or ‘ceilidh’ bands (as they were usually referred to) formed another category, specialising in playing for country-type dancing. Such bands had been growing enormously in popularity and there was scarcely a PTA dance or sports club social for which the organisers did not at least consider the option of hiring one of the local folk dance bands for a ‘barn dance’. Since the band came complete with a caller to instruct the dancers the whole event was ready-organised, with little for the committee to do but provide the food and enjoy themselves. These bands were in great demand and able to charge high fees.

Music Folk can serve as an example of one such ceilidh band. It was founded in 1980, growing out of an earlier Open University folk club, then becoming associated with a local folk dance club when the caller joined. It consisted of six players on melodeon/harmonica, double bass, piano-accordion, recorder, acoustic guitar and fiddle plus a dance caller. Most of the players had academic connections: a couple worked at the Open University as editors, one had a Ph.D. in physics, and another was an FE computer lecturer who also brought along her son – still at school but already an effective double bass player (family links within bands were common in local folk music). The fiddler alone had a different background, working with the Water Board and joining through a personal motor cycling connection. Some of the players were self-taught, two were classically trained but had had to adapt to folk style, one had previously learnt the piano formally but had taught herself the piano-accordion for the group, and two had passed A level music – a mixture of learning styles and musical backgrounds characteristic of the folk music world. They played lively and melodic music and clearly derived the greatest enjoyment from the various medleys of familiar tunes which they played as ‘so many yards of music’. Their own preference and the view they had of their music was to emphasise ‘traditional’ forms, some based on manuscript collections, others on newer compositions by other folk musicians which were classified as ‘within the tradition’ – pieces like ‘The boys of blue hill’, ‘Orange and blue’, ‘Oh Eliza’ and ‘The king of the fairies’. They had begun to establish themselves as one of the recognised local ceilidh bands in the area, performing every two or three weeks at barn dances for local PTAs or social clubs, folk dance events, folk clubs and various private occasions, concentrating on the nearby area to avoid too much travelling. Their fees scarcely covered expenses, and were in any case sometimes handed back when they played for a local charity like Willen Hospice. They thus had some way to go before they reached the popularity of older bands like the Gaberlunzies or the Cock and Bull Band, and were still trying to expand their clientele by pressing their telephone number on all likely contacts. But they were already experienced enough to need only the occasional rehearsal in each other’s homes and to be very aware of the satisfactions of joint playing: ‘2 + 2 = 5’, as one put it, for ‘by playing with other people you get another dimension to performance’.

Figure 12 (a) and (b) ‘Folk on the Green’ in 1981: the annual folk event on Horsefair Green in Stony Stratford, attended by hundreds of participants and scores of active performers

Figure 13 Publicity for local folk events: posters by the local teacher and musician Rod Hall

A related set of activities were those of the Morris dancing groups. The best known were the Stony Stratford Morris Men with their female counterparts Old Mother Redcaps (named after a historic local hostelry), but there were also the more recently founded Garland Dancers, and, further afield but still with Milton Keynes links, the Akeley Morris Men and Brackley Morris Men. These were not primarily music groups but did include the kind of music that overlapped with that of the folk bands. There was overlap of personnel too, and Morris dancers frequently appeared at folk festivals and fêtes, accepted by local folk musicians as belonging to the same folk world.

It is not easy to define precisely the kind of music played in the folk clubs and groups. It varied not only between different groups and clubs, but even at the same clubs on different nights; and it was not fully agreed exactly where the boundaries of ‘folk’ should be drawn. Generally the music known locally as ‘folk’ tended to be melodic, relatively quiet and intimate in presentation (in contrast, for example, to much rock or country and western music), with particular emphasis on song and often an explicitly regional flavour, from Ireland, Scotland or particular English counties. The range of instruments was wide. In Milton Keynes folk groups these included: mandolin, banjo, guitar (often but not always acoustic), fiddle, melodeon, concertina, string bass, ukelele, harmonica, recorders, flute, euphonium, and, in a few cases, dulcimer, psaltery, pipes and tabor, crumhorn or washboards; also occasionally piano and percussion (drums, cowbells, wood blocks); and, very important, the voice. There was thus no one set combination of instruments or number of players, so groups of from three up to six or eight (the latter especially in dance bands) were quite normal, with a whole variety of instruments being played by their often multi-instrumental members.

The ‘folk’ness was indicated not so much by the instruments or musical works as by playing style and the musicians’ approach to it. This was often different from classical tradition even when the instrument was the same. For example there was a marked contrast between classical violin playing and the short-bowing, largely one-position, and loosely held form of folk ‘fiddling’. The pattern of learning and transmission was also distinctive. The main emphasis was on memory and playing by ear rather than the characteristically classical reliance on written forms. On the other hand there was less opportunity for extensive improvisation than in jazz and more attention to fairly exact reproduction of songs and tunes in broad outline (there could be detailed variation in performance). Given the repetitive stanzaic form of much of the music, learning an item was quick and bands often had enormous repertoires without much need for frequent rehearsal. Paralleling this, learning to play or sing folk music was commonly (though not always) learnt ‘on the job’, inspired by recordings or live performance instead of or as well as written music.

Above all the ‘folkness’ of the music was assured for the participants by its enactment within a setting locally or nationally defined as ‘folk’, and by a strongly held, if not always articulated, set of ideas about the kind of enterprise in which they were engaged. Understanding this needs a short excursion into the scholarship and development of folk music.1 Briefly, popular views of ‘folk music’ are still much influenced by ideas developed with particular explicitness in the nineteenth century according to which folk tradition was handed down over the ages, primarily by little-educated country-dwellers. The lore of this ‘folk’ was held to be simple and spontaneous, owing more to ‘nature’ than conscious art, more to communally held tradition than individual innovation, with each nation and, to an extent, each region having its own ‘folklore’ implanted deep in the soil and soul of its people. These general ideas were reinforced in the late-nineteenth-and early-twentieth-century collections by Cecil Sharp and similar collectors of ‘folk songs’ and ‘folk music’ which were seen as springing from national or regional roots over the ages, remembered especially by the older people, and pertaining essentially to unlettered country folk.

The views of these earlier scholars and collectors fundamentally influence the whole concept of what it means (still) to classify something as ‘folk’. During this century the concept has been widened to include urban and industrial forms like mineworkers’ or political songs, expressing ‘the people’ against authority. The British ‘Folk Revival’ in the 1950s introduced yet another twist, together with the popularity of the acoustic guitar and the beginning of the present system of ‘folk clubs’ from the mid 1950s, but these new forms too became assimilated within an overall ‘folk’ ideology and the staple repertoire continued to be validated by reference to regional rural roots or drawn from the collections and styles authorised by such bodies as the English Folk Dance and Song Society or books like The Penguin book of English folk song or A. L. Lloyd’s Folk song in England.

This series of assumptions is not just a matter of intellectual history, for it still influenced how contemporary folk music performers in Milton Keynes interpreted their activities. In practice their music came from varied sources (i.e. not just oral and regional tradition ‘through the ages’), it was played on a variety of instruments (guitars and drums, as well as the ‘older’ fiddles, pipes or vocals), it contained new compositions as well as older songs, and was carried on by players both with and without formal musical training. They saw themselves nevertheless as carrying on a tradition from the past – and in a sense, of course, they were right. For the music and modes they cultivated, changing though they were, were indeed broadly set within recognised conventions of what was to be counted as ‘folk music’ – even though the images of the modern executants may have been set not so much by ‘rural tradition’ as by the intellectual perceptions of certain scholars and collectors. It may be questionable whether there really ever was a distinctive corpus of music produced by a definable ‘folk’ in the rural setting envisaged by the purists, but this belief, conjoined with socially recognised definitions and practices, provided an implicit authorisation for ‘folk music’ as it was being performed and enjoyed in urban settings in the 1980s.

This complex of ideas was part of a more general philosophy, operating nationally, about the nature of ‘folk music’ and ‘folk musicians’. At the local level, these ideas were largely implicit rather than an articulated ideology, but the underlying assumptions emerged when people were challenged to explain the nature of their activity, as well as in the vocabulary used in discussing music and music-making. Local musicians spoke of the ‘pastoral’ or ‘traditional’ nature of their music and regarded the test for whether a song (even a new song) really was ‘folk’ as being whether it passed into the ‘oral tradition’: ‘if it’s still valid after twenty years then it’s folk’. Some valued contact with ‘the regional roots’ of their music (one band, for example, arranged a tour of Scotland ‘to find more tunes’), and musicians liked to stress their own links with particular English or Celtic origins. They associated their music, and hence themselves, with ‘the folk’ – ordinary people – in the past and the present.

When one looks at how ‘folk music’ was actually organised in Milton Keynes, however, it is striking how far it was at variance with many of the tenets of this implicit ideology.

First, the social background of the local folk music participants was far from the rural unlettered ‘folk’ of the ideal model. They were a highly literate group, most of them in professional jobs and with higher education; many had degrees, even postgraduate qualifications. There was a high proportion of teachers, and other jobs (to give some typical examples) included banker, accountant, medical researcher, pharmaceutical chemist, civil engineer, business director, personnel manager, and social worker. Members of the folk music world liked to think of themselves as in some sense ‘the folk’ or at any rate as ‘classless’. In a way they were justified: once within a folk club or band their jobs or education became irrelevant. They were thus themselves startled if made to notice the typical educational profile of folk enthusiasts. If any of the local music worlds could be regarded as ‘middle class’ it was that of folk music, for all that this ran so clearly counter to the image its practitioners wished to hold of themselves.

A further complication was the variety of learning and transmission modes. There was a tradition of self-learning and playing by ear, and it was unusual to see written music used in performance, but in practice many folk performers could also read music or had learnt an instrument within the classical mode. This was hardly surprising considering the typical educational background, but it certainly made the picture more complex than it first appeared. Similarly, in spite of the emphasis on oral transmission, writing in fact played an important part. Many songs in the recognised folk corpus derived from published collections, and printed or manuscript songbooks were also used (several local players had consulted manuscript archives in Cecil Sharp House in London). Certainly there was also oral transmission and singers often learnt songs from each other and from recordings, but the highly literate background of antiquarian scholarship was one prominent strand in the folklore movement and its local practice.

Despite the broadly agreed parameters of the ‘folk’ model there was also controversy about exactly where in practice the boundaries of folk music should lie. At the local level this was expressed in two opposed camps. There were those operating mainly on the folk club and folk festival circuit, regarded by many as the context of ‘folk music’ today – often well educated, professional and middle-aged with few if any teenage adherents. This wing was judged by the other side to be stuffy and ‘narrow’, opposed to innovation. Others favoured the more experimental and – in their eyes – creative mode of trying out new forms and combinations, in particular blending with rock, using electric guitars, amplification and a greater emphasis on percussion, even sometimes referring to their music as ‘folk-rock’. Several musicians also played blue grass or jazz along with ‘folk’ or were co-operating with orchestral players in the classical mode. Some wanted to break away from the ‘traditional folk club’ paradigm and tried out clubs for a wide range of music (as in the short-lived Cannon Blues and Folk Club or Muzaks), not surprisingly regarded as ‘fringe’ by the more purist enthusiasts. Bands in this mode – Merlin’s Isle, for example – could not always find a ready niche for their performances: not ‘folk’ enough for the folk clubs (to which in any case they did not wish to confine themselves), not close enough to rock to be welcome in many pubs. Folk music of this innovative kind was having quite an influence. A blend of various types of music centred round, or at least including, accepted ‘folk’ genres helped to make the annual ‘Folk on the Green’ day so popular, and the musical plays on local historical themes such as All Change or Days of Pride also owed much to the talents of a local teacher who combined his primary devotion to ‘folk’ music with a classical interest (further details in chapter 13, p. 164).

The controversy between the folk club purists and the (mostly younger) experimenters was unlikely to have any quick resolution. Both sides in fact accepted innovation in instruments, presentation and composition, and even some of the established clubs were trying to transform a narrow ‘folk’ image into a more open one, as in the Stony Stratford Folk Club’s change of name to the Song Loft, and the Hogsty Folk Club to Hogsty Music. The difference was thus partly just in emphasis, but it also lay in the performance settings (folk clubs and festivals on the one side and the less specialised pubs, clubs and halls on the other) and in differing personnel and social groups. In the end both sides shared something of the same basic model of ‘folk music’ as well as a remarkable commitment not only to shared experience in the beauty of their music but also, in an obscure but deeply felt way, to the ethical and imaginative values somehow enshrined in the notion of ‘folk’.

Perhaps, then, when one comes down to its actual realisation in the local context, there can be no real definition of local ‘folk music’ beyond saying that it was the kind of music played by those who called themselves ‘folk’ performers. The classification was ultimately forged through current social institutions and how these were imaged by the participants rather than in purely musicological terms or because of any actual historical pedigree (handed down orally through the ages, for example). ‘Folk music’ was just that currently performed within, or in association with, the local ‘folk world’ described here.

For those involved in that world – complicated and contentious as it sometimes was – the sense of identity and value it brought seemed sometimes to be the most meaningful experience of their lives. Just about all the local folk enthusiasts were people in highly regarded and satisfying jobs. Yet for many of them, it was the ‘after hours’ folk music activities that they seemed to live for. Indeed for some, beyond the bare hours spent at work, there appeared to be literally no time for anything else but folk music anyway – out just about every night at one or other of the local folk clubs as either audience or performer, or, on the few free evenings, practising at home; and if travelling away from home, then visiting folk clubs there. Others drove themselves less hard, but for many of them too the weekly or twice-weekly visit to a folk club or performance with their own folk group took up much of their spare time and interest. As one local performer said, confessing that he knew nothing about any other local music (in fact was surprised to hear there was any), you get a kind of ‘tunnel vision’, seeing folk music only.

Folk music was actively practised by only a small and select minority in Milton Keynes. But its influence as both pleasant melodic music to listen to and the evocation of the kind of romantic ‘world we have lost’ so dear to English urban dwellers was felt in a range of contexts: through the creative use of folk music in perhaps unexpected settings like the Stantonbury musical plays on local historical themes or – even more widely – through the remarkable popularity of folk-based dance bands for annual barn dances at every kind of local social gathering from PTAs or sports clubs to ladies’ keep-fit or fund-raising events. For the active folk performers, however, few though they were, the world of folk music was something which gave a deep meaning and value to their view of themselves and their experience: something that they ‘spend more time thinking about than their work’; they ‘live for folk’.