Читать книгу The Hidden Musicians - Ruth Finnegan - Страница 23

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление9

The country and western world

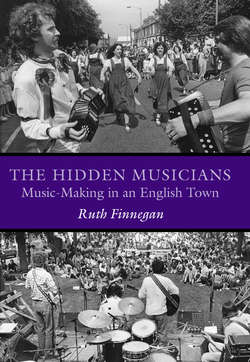

Among certain sections of the Milton Keynes population the music labelled ‘country and western’ was extremely popular, and country and western events attracted a large and regular following. There were two established bands with regional – even national – reputations as well as local engagements; other more fluid bands; a flourishing country and western club with a healthy bank balance, known in the region as well as the immediate locality; several pubs putting on country and western evenings; ‘Wild West’ groups whose shows added variety and glamour to country and western musical performances; and a pool of regular attenders, based on family rather than just individual loyalty.

As with folk music I will start with the club organisation, before going on to explain the background and wider ramifications. In this case there was just one leading club, so a description of one of its events can provide a good introduction to the country and western world.

The Milton Keynes Divided Country and Western Club had been going strong since the mid 1970s, when it was founded by a small group of local enthusiasts in Bletchley. It held fortnightly Sunday meetings in a hall borrowed from the local football club next to the large sports fields on the edge of Bletchley. It was not easy to find for the newcomer – off the bus routes, across a narrow hump-back bridge over the canal, and past the playing fields – but, once known, the path was familiar to its many regular attenders who came on foot, bus, cycle, or (most frequently) in a shared car or taxi.

On this particular occasion – typical of many – the visiting band was due to start around 8.00 p.m. with the doors opening at 7.00. By 7.45 the hall was already well filled with 80 or so people (it rose to about 120 later on). Music was coming from records on the stage at one end, where the band members were setting up their instruments. The bar was at the opposite end and a table set up by the entrance for committee members ‘on the door’ to take entrance money, greet old and new members with a flourish and sell club mementoes. In contrast to rock and jazz events, the audience sitting round the tables was family based, with roughly equal numbers of men and women, several children, and people of every age from the twenties upwards, including middle-aged and elderly people; only the late teenagers were absent. It was a ‘family night out’ with most people in groups rather than singly, a policy encouraged by the club’s organisers.

The club’s name – the Divided Country and Western Club – indicated certain options. One of these was in dress: ‘divided’ between those who chose to come dressed ‘just as you like’ and those who preferred ‘western dress’. Either was acceptable, and around half had opted for one or another version of ‘western’ gear. Some had only a token cowboy-style hat or scarf, but many of the men had elaborate costumes – a leather-look waistcoat, large leather belt with a holster and replica revolver on one side and bullets on the other, coloured neckcloth, jeans, badges (a star marked ‘Sheriff Texas’ for example), leather boots, a decorated cowboy hat, and sometimes a long coat which could be pushed back with a swagger to reach the belt and holster. Some women too were wearing hats or jeans, or in some cases leather jerkins or guns. The men in particular showed off their finery, strutting around in their long coats with hands on holsters. One strikingly smart group were dressed in matching black neckcloths and decorations: they were the local ‘Wild Bunch’, western enthusiasts who took a prominent part in local country and western events.

The band was introduced soon after 8 p.m. by the compère, the club secretary. It was an all-male group who had been to the club before and were known to many members; coming from Aylesbury, about half an hour’s drive away, they were regarded as nearly local. They were given a big build-up and personal welcome by the compere, while the secretary welcomed individual visitors from other clubs to interest and smiles from his listeners – an established custom in country and western clubs, in keeping with their general atmosphere of friendliness and personal warmth.

The band then started up with electric guitars, pedal steel guitar, drums and vocals, with the main singer very much in the lead. The audience were free to talk, drink and walk round during the band’s playing and later on to dance – a sociable evening out. But there were also some restraints on audience behaviour, and the setting was recognised as at least partly a musical one; children were discouraged from running round noisily during the performance and the close of each song was clearly marked. The band’s playing was not just unheard background, either: the music was familiar to the audience – part of its appeal – and there was a lot of beating time and occasionally some quiet joining in with the catchy and rhythmic songs; the applause after each item was almost invariably highly enthusiastic. As the evening went on, more and more people got up to dance, adding to and developing the music through their rhythmic movements in the dance – one of the age-old modes of musical expression and appreciation. The atmosphere was relaxed and unselfconscious, and most people whatever their age, sex or build looked remarkably carefree as they danced to the band – the middle-aged woman in her tight jeans, jersey and big leather belt over her well-rounded bulges, the visiting technician and grandfather with his broken smoke-stained teeth, gleaming gun and cowboy gear, the young wife out for an evening with her husband, drawn in by his interest in country and western music and now sharing his enthusiasm – and scores of others.