Читать книгу The Hidden Musicians - Ruth Finnegan - Страница 22

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление8

Jazz

The world of jazz was more fragmented than those discussed so far, in its musical styles, social groupings, training, and the model drawn on by participants. Jazz was regarded as distinctive, but at the same time as shading on one side into rock or folk, on the other into brass band or classical music. Within ‘jazz’ too there were several differing traditions each with its own devotees, making up networks of individuals and groups rather than the more explicitly articulated worlds of, say, brass band or folk music. But, as will become clear in this chapter, jazz was certainly played and appreciated in Milton Keynes. To the outsider it was less visible than classical, operatic and brass band music on the one hand or the plentiful rock bands on the other, but for enthusiast ‘in the know’ there were many opportunities for both playing and hearing jazz.1

Take first the various playing groups. In the early 1980s there were about a dozen jazz bands in or around the Milton Keynes area. Some were local only in the sense of having one member living in the locality and making regular appearances there, but for many most of their members were locally based. A few were short lived, but some had been going for years (often with some change of personnel or developing from an earlier group) and in many cases put on regular performances with a healthy local following. Three of the bands playing in Milton Keynes in the early 1980s – the Original Grand Union Syncopators, the Fenny Stompers and the T-Bone Boogie Band – can illustrate some of the accepted patterns as well as differences in the local jazz scene.

The first two had much in common. They shared the same basic jazz format of six players: clarinet or saxophone, trumpet or cornet, and trombone (the ‘front line’ where the solo spots were concentrated) with a rhythm section of banjo, percussion and (string) bass, some players doubling on occasion as vocalists. Both bands put on regular performances both locally and (less often) further afield to enthusiastic audiences.

In other ways they differed considerably. The Original Grand Union Syncopators started up in Bletchley in 1975, reputedly the first real jazz band in Milton Keynes. From the start they were favoured by the new city planners, with whom the band leader (himself a senior management officer in local government) seemed to have consistent good relations. In contrast to other small bands they were encouraged to appear alongside the classical groups on large-scale occasions like the February Festival or the televised city centre Sunday Service in December 1981, and to represent Milton Keynes in cultural exchanges with its twin town of Bernkastel. Despite this official interest, the band very definitely regarded itself as an independent group, making a point of taking its name not from anything redolent of the ‘new city’ but from the historic Grand Union canal.

Their main performances were in local pubs and clubs, where they had built up a core of 50 or 60 regular followers. By the early 1980s they were putting on around 60 gigs a year, mainly of ‘trad jazz’ music, and reckoned they had a repertoire of around 200 tunes. They had occasional rehearsals in the winter (about once a month), but for the rest of the year were busy enough with performances not to need additional practice, appearing frequently in the Bull in Stony Stratford, the Swan in Woburn Sands, or the King’s Arms in Newport Pagnell. Their most favoured engagements – as for most jazz bands – were ‘residencies’, as when they appeared regularly on alternate Sunday evenings at the White Hart in 1980 and fortnightly at the jazz evenings at the Cock in North Crawley, as well as regular appearances at (among others) the Woughton Centre and the Great Linford Arts Centre in Milton Keynes itself and WAP in Wavendon. They also travelled further afield to perform at jazz clubs at Watford or Nottingham as well as playing for private occasions like weddings or, from time to time, free for causes like Christian Aid or local charity organisations.

They took themselves seriously as musicians and as propagators of trad jazz, but had no intention of turning professional or regarding their playing as anything but a hobby, and so were content just to earn enough from fees to cover expenses like transport, amplification, advertising and telephone. The current members were in full-time paid employment: art lecturer, local government officer, teacher, musical instrument repairer, artificial limb maker and graphic artist. They could thus afford to engage in their passion for jazz in both the Original Grand Union Syncopators and the other bands they from time to time played or guested in, without having to worry unduly about finance. They did encounter the familiar difficulties of competing commitments, and the frustration of never quite being able to get a really flourishing jazz club going. Despite the problems, the band had stayed together as a named group for ten years or so, though, typically for a jazz band, there had been occasional changes both in instrumental composition and in personnel as people moved to other areas intending to resurrect jazz there too in the same way as the Original Grand Union Syncopators had done for Milton Keynes.

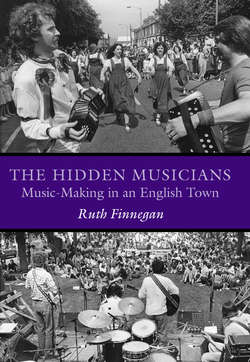

Figure 15 The Fenny Stompers in 1987: popular traditional jazz band playing since 1978, based on a constant nucleus of two brothers, Dennis and Brian Vick: publicity photograph in their band uniform

The Fenny Stompers had the same enthusiasm for traditional jazz but in other respects were very different. In contrast to the higher education or art diplomas of most of the Original Grand Union Syncopators all but one of the Fenny Stompers had finished full-time education at 15 or 16 and, by now in their thirties or forties, were involved in such work as warehouseman, self-employed plumber, school lab technician and carpenter; there was one teacher. Unlike the Original Grand Union Syncopators, some of whom had had some formal musical training, they were mostly self-taught as instrumentalists. They were formed in May 1978 under the title of Red River Stompers, soon changed to Fenny Stompers after Fenny Stratford, where their leader Dennis Vick lived. Despite some changes of personnel, especially among the drummers, the band with its nucleus of two brothers quickly took off, not least because of its leader’s effective exploitation of free publicity in local newspapers. Within a few years their smart uniform of pink and white or red shirts with black trousers became well known to jazz audiences around the area and beyond.

By the early 1980s they were in demand for gigs two or three times a week. They performed not only at local pubs and clubs like the Bull Hotel in Fenny Stratford, the Bletchley Conservative and Naval Clubs or the Craufurd Arms in Wolverton, but also for paid performances at, for example, the Riverboat Shuffle for the Wimbledon Squash and Badminton Club, the Horwood House fête arranged by British Telecom, or the British Stock Car Racing Supporters’ Dinner Dance in Solihull, as well as working men’s clubs around the area. They also played for fund-raising events, charitable occasions for senior citizens, and a Women’s Institute Christmas party for the disabled. They also managed to arrange some regular bookings like the monthly Sunday lunchtime spot at the Swan Hotel in Fenny Stratford during 1979, and regular appearances at Ye Olde Swan, Woughton-on-the-Green, or the Coffee Pot at Yardley Gobion.

Like other bands, they too failed to get a permanent jazz club going within Milton Keynes to match the long-continuing jazz evenings at the Cock in North Crawley to which many enthusiasts went, and their various local attempts (like the Swan sessions in Fenny Stratford) were short-lived. But their playing regularly drew audiences of 70–100 people, and their total of around 140 performances a year by 1982 showed the appeal of jazz in the area despite its relatively fragmented organisation. They were said to be less adventurous musically than the Original Grand Union Syncopators and with a smaller repertoire, but their particular version of Dixieland New Orleans jazz for people ‘to sing along to and have a good time’ was popular with local audiences from a whole range of social backgrounds and organisations.

The T-Bone Boogie Band was different yet again. As they themselves publicised it, they went in for ‘rhythm and blues with an element of self ridicule’, for ‘blues and mad jazz’ and, as one of their admirers expressed it, ‘boogie, ragtime, bop and riddum ’n’ blooze’. They presented themselves as a zany ‘fun band’, but their act followed many traditional jazz and blues sequences, with beautiful traditional playing interspersed with their own wilder enactments of blues. They spoke of these as ‘improvised out of nowhere, on the spur of the moment’, but they were in practice based on long hours of jamming together as a group.

The nucleus of the band was the headmaster of a local school for handicapped children, Trevor Jeavons, an expert on the boogie piano, and Tracey Walters, a local youth worker who played the harmonica as well as producing extravagant vocals and wild clowning around for the audience. In all by 1982 it consisted of six players, including a schoolboy and a social worker. The somewhat unexpected but extremely popular combination of instruments was acoustic piano, saxophone, lead and bass guitars (sometimes replaced by string bass), harmonica, drums and vocals. The group had grown gradually from a series of informal jamming sessions by Trevor Jeavons and Tracey Walters in the foyer of the Woughton Centre at Sunday lunchtimes under the informal title of the Jam Band which used to draw in a large and enthusiastic audience. By September 1981 they had taken on the name of T-Bone Boogie Band to indicate both their rhythm-and-blues character (with a passing reference to T-Bone Walker as well as the T for their lead vocalist Tracey) and Trevor Jeavons’ boogie piano with its Dixieland overtones. They started getting widespread invitations to gigs, but – all busy people – preferred to keep these to about one a week, appearing regularly at their home base of the Woughton Centre as well as for a scattering of local social occasions and a few pub and outdoor performances.

Figure 16 Trevor Jeavons and Tracey Walters in action: the two leading members of the T-Bone Boogie Band, the popular ‘community mad jazz and blues band’

They saw themselves as ‘a community band’, playing ‘to give other people enjoyment … and for our own enjoyment as well’, a hobby rather than professional enterprise. When they were approached by a recording company and offered money to go professional, they turned it down. They did agree to do a recording live at Woughton with a local amateur recording engineer (which immediately sold out to local fans), but then decided to disband for a time, saying their performances were getting too serious and they wanted a rest. The upshot was the first of several ‘Final Renditions’ and ‘Final Thrash Goodbye Concerts’ – but both then and later, they were soon back again for a ‘triumphant return’ with only minor changes; their playing was too enjoyable and too well appreciated locally to keep away from for long.

Their entertainment aim was obvious in their performances. The lead singer’s extravagant antics, the excited and active audience, the explicit air of enjoyment and their unconventional clothes were all part of the occasion. ‘We like to entertain people’, as Trevor Jeavons explained it, ‘which is why we dress rather outrageously sometimes. People like it.’ They themselves encouraged this extravagant image further by the ironically drawn self-portraits in their advertisements, designed to bring out the ‘madness’ so much appreciated by their fans. On their favourite home ground, the foyer in the Woughton Centre, their audiences regularly included people of all ages ‘from babies to OAPs’, which was just how they wanted it, and it was usual wherever they played for the venue to be filled to capacity. Some groups followed them from gig to gig, replying energetically to their jokes (musical, verbal and gestural), and T-Bone Boogie playing always stirred up the audience, not so much to actual dancing or singing along but to an active engagement with the performance. The band’s own enjoyment was also clear as they played, with an air of mutual interaction, appreciation and, in a sense, pleased surprise as they presented their pieces from jokey songs like ‘Little fishy’ or ‘My baby’s gone down the plug hole’ to a more traditional slow ballad.

The presentation of the T-Bone Boogie Band’s music was designed to bring out their ‘crazy’ image, eliciting active audience participation and a ‘fun’ atmosphere. The emphasis on enjoyment should not obscure the enduring musical centre of their performances, however. The cassette that they recorded ‘Live at Woughton’ in 1982 was treated seriously in the ‘Album of the Week’ column in one of the local newspapers – which seldom took a local example – on the grounds that the band had ‘proved that “fun music” can also be good music’ in their ‘remarkably professional sounding debut offering’. There was certainly far more to their playing than the visual clowning, not least the lyrics, music and piano playing of Trevor Jeavons himself, and the band’s practised improvising in the traditional blues style. In some eyes the T-Bone Boogie Band’s light-hearted exhibitionism made them less orthodox than the Original Grand Union Syncopators, Fenny Stompers, Momentum or the Mahogany Hall Jazzmen; but, whatever their idiosyncratic presentation, they were still part of the local jazz and blues offerings, one of the few local jazz groups performing at the local Great Linford Jazz Festival in July 1982, and immensely admired by some local jazz enthusiasts for their musical as well as ‘fun’ interest. Together with the other jazz bands in the area – all in practice varied in terms of instruments, personnel, background and detailed musical tastes – the T-Bone Boogie Band formed part of the contemporary realisation at the local level of the traditional jazz and blues storehouse of musical themes and idioms in a form no less ‘real’ than the more ‘serious’ offerings of other bands.

These three bands were not the only jazz groups functioning in Milton Keynes, and the picture must be completed by briefly mentioning some of the others. These included the five-piece Momentum, putting on about twenty performances a year, mainly early fifties bebop, on a combination of flugelhorn/trumpet, reeds/saxophone, bass, keyboards and drums; the Mahogany Hall Jazzmen playing Dixieland early jazz and ragtime regularly once a fortnight or so in local pubs; and the long-lasting Wayfarers Jazz Band performing ‘mainstream’ and Dixieland jazz in pubs, wine bars, social clubs, colleges and fêtes in both the Milton Keynes and the Luton-Dunstable area – not quite a ‘local’ jazz band, though one very active member lived locally. Among the other local or near-local jazz bands (several of them overlapping in personnel with those already mentioned) were the Alan Fraser Band, the twosome blues and early jazz Bootleg Band, the Concorde Jazz Band, the Holt Jazz Quintet, the zany 1920s New Titanic Band with its stage pyrotechnics, the very fluid Stuart Green Band, the Colin James Trio, Oxide Brass and the John Dankworth Quartet (this last based on WAP and giving occasional performances there); there were also the short-lived Delta New Orleans Jazz, the New City Jazz Band, the Pat Archer Jazz Trio and (for a few struggling months) the MK Big Band.

All these bands put on public performances, sometimes singly, sometimes on a regular basis at particular pubs and clubs in the area. In addition there were probably several other groups who met more for the pleasure of jamming together or playing on private occasions than for taking on public engagements. The Saints group of six 11-year olds on clarinet, flute, trumpet, percussion and piano, for example, played jazz or pop together and performed in school assemblies and the end-of-term concert, while the highly educated all-female Slack Elastic Band played ‘big band’ and popular jazz of the thirties on trumpet, saxophone and string bass as a rehearsal rather than performing band, and the newer Jack and the Lads with trumpet, saxophone, guitar, bass guitar and drums were initially performing just for enjoyment on the Open University campus. There were doubtless other groups playing privately – an opportunity more open to them than to the larger and louder brass bands, operatic groups or amplified rock bands.

The administration of jazz bands differed from classical, operatic and brass band groups in that they seldom adopted the formal voluntary organisation framework. The numbers were smaller, for one thing: with a couple of exceptions like the short-lived MK Big Band, there were usually five or six players so that jazz groups were run on personal, not bureaucratic lines, geared to individual achievement rather than the hierarchical musical direction characteristic of larger groups. This also fitted their open-ended form, for though there were certain common groupings of instruments, the actual instrumental composition of jazz groups was more variable than in most other musical worlds.

This fluidity was also evident in the music-making itself. Jazz musicians were tied neither to written forms nor to exact memorisation, but rather engaged in a form of composition-in-performance following accepted stylistic and thematic patterns. This, of course, is a well-known characteristic of jazz more generally – not that anyone has ever managed to define ‘jazz’ too precisely – so it was no surprise to find it at the local level in the views and behaviour of those classifying themselves as jazz players. Local musicians often commented on the freedom they felt in jazz as compared to either classical music or rock. One commented that with rock ‘it’s all happened already’ (i.e., already developed in prior rehearsals), whereas in jazz the performance itself was creative; another player explained his enthusiasm for jazz through the fact that ‘it allows a lot of expression for the individual’. Similarly a local jazz drummer talked about how in classical playing, unlike jazz, he had had ‘no real chance to create in a number, no choice about what to do’ and so ultimately preferred playing jazz to classical music.

This aspect was also very apparent in the performance of local jazz players. Far more than other musicians they would break into smiles of recognition or admiration as one after another player took up the solo spot, and looked at each other in pleasure after the end of a number, as if having experienced something newly created as well as familiar. As one local jazz player put it, ‘we improvise, with the tunes used as vehicles, so everything the group does is original’. Local jazz musicians often belonged to several jazz bands, moving easily between different groups. A musician who played both jazz and rock explained this in the following terms: with a rock band you are dependent on joint practising since the whole performance is very tight, whereas with jazz, providing you have learnt the basic conventions, ‘I can play traditional jazz with a line-up I’ve not met before.’ Jazz groups were thus less likely to have regular rehearsals than the other small bands: when they did play together it was often based on their general jazz skills rather than specific rehearsals of particular pieces. This open nature in performance also explained the high proportion of jazz ‘residencies’ by which the same band was booked to appear at the same venue once every fortnight or so. Audiences were likely to get tired of the same music time after time (a problem for rock and country and western bands), but were not bored by the more fluid jazz performances: ‘numbers are practically made up on the spot’.

When jazz enthusiasts spoke of local jazz they often described it in terms of the venues where one could regularly hear jazz bands performing. Jazz was less prominent locally than other kinds of music and apparently did not have the historical roots found among local brass bands, operatic groups or choirs. But by the early 1980s there was a series of jazz clubs and pubs in and around Milton Keynes which could be visited in rotation by an enthusiast over any given week, chief among them being the Cock and the Bull Hotels in Stony Stratford, the Bull (Newport Pagnell), the Galleon (Wolverton), the Holt Hotel in Aspley Guise, and the Cock Inn in North Crawley. Other venues included the Swan at Fenny Stratford, the Coffee Pot at Yardley Gobion, Levi’s bar at Woughton House Hotel, the Bedford Arms, Ridg-mount, the Magpie Hotel, Woburn, the foyer bar at the Woughton Centre, the Swan in Woburn Sands, the regular ‘Jazz at the Stables’ evenings at WAP, Muzaks at the New Inn, and, for a few weeks in mid 1981, the Eight Belles in Bletchley. Some pubs organised weekly or fortnightly ‘jazz clubs’: for example the Bull in Newport Pagnell at one point ran a jazz club every Wednesday alternating the Mahogany Hall Jazzmen and the Alan Fraser Band, while the Holt Hotel Jazz Club functioned every Thursday. Other pubs put on either occasional jazz groups or, more often, arranged weekly, fortnightly or monthly jazz performances on a regular basis.

Some of these arrangements lasted longer than others, but at any one time there was live jazz being played in the area at least once or twice in the week, often more. For example June 1982 saw the following: the Original Grand Union Syncopators on alternate Thursday nights at the Woughton House Hotel, with the Cock Inn in North Crawley continuing its fortnightly jazz nights (already going for five years) on the other Thursdays; Momentum on alternate Fridays at the Cock Hotel, Stony Stratford; the Fenny Stompers on the last Saturday of every month at the Coffee Pot, Yardley Gobion; Tuesday jazz evenings at the Woughton Centre, alternating between the Alan Fraser Band and the Original Grand Union Syncopators; and the Mahogany Hall Jazzmen on the first and third Wednesday of every month at the Bull in Newport Pagnell. Most of these performances were in local pubs, and thus in a sense financed through market mechanisms and private enterprise. Unlike classical music and to some extent brass bands, jazz groups and performances, with the possible exception of the Original Grand Union Syncopators, had relatively little patronage from public bodies.

The regular jazz evenings in local pubs and clubs were the most visible performances. But bands were also asked to perform at private occasions like parties or weddings, or to entertain at local clubs (above all the working men’s clubs), at special evenings for, say, the Angling Club, Bletchley Town Cricket Club, a local Conservative Club or Women’s Institute, or at fêtes out of doors. Groups also played free for such causes as a local scouts jamboree appeal, Christian Aid, the Jimmy Savile Stoke Mandeville Appeal and Woburn Sands Brownies. Enthusiasts, of course, were also listening to broadcasts (including jazz on local radio stations, some not far away) and the occasional professional appearances in the area, like the successful concerts organised at WAP or the ambitious but sparsely attended Jazz Festival at the local Linford Arts Centre in mid 1982. In addition, music with a jazz flavour could be heard at other local events, notably at the Bletchley Middle School Festivals, when the specially composed pieces sometimes included jazz, and in events otherwise mainly devoted to folk, brass band or classical music modes. The main jazz world, however, insofar as it existed as something separate in Milton Keynes, was primarily represented by the players in the established jazz groups and their followers in the area.

Who were these local jazz players in Milton Keynes? Practically all fell towards the amateur end of the ‘amateur/professional’ continuum in the sense both of relying on other means than jazz for their income and in their view of their musical activity as basically enjoyment rather than job.2 The question is an interesting one, however, because of the conflicting general views about this. For some, jazz is ‘the people’s music’ (Finkelstein 1975), whereas others suggest that it is now an intellectual rather than truly popular form (see Collier 1978, pp. 3–4; Lloyd 1974). This ambiguity actually fitted quite well with the heterogeneous membership of local groups. On the one hand there were many highly educated jazz players, including teachers, administrators and community workers, and several who had developed their jazz enthusiasm at art school. But as demonstrated by the Fenny Stompers among others, there were also players who had left school early, were in skilled or semi-skilled manual work rather than professional jobs, or were unemployed; some were still at school. The one clear pattern was that they were overwhelmingly male (apart from the one explicitly female band) and predominantly in their thirties or forties. There were a few younger players like the primary school group, but essentially jazz playing seemed not to be a teens or twenties pursuit.

This lack of any single set of social characteristics also came out in the different channels through which local players were recruited into jazz. Some began through classical music at school, with the characteristic classical emphasis on reading music and executing it with little variation. Players coming through this route were usually confident about their instrumental skills and musical understanding but less happy performing in a context where – as in jazz – close reliance on written music was not appropriate; indeed such players were sometimes criticised by co-players for their lack of flexibility. Rather more players had taught themselves, sometimes via an interest in rock music. This often included some hints or informal help from friends or colleagues, but seldom any formal teaching (as that is understood in the classical music world), and meant learning jazz skills through listening to and copying recordings and, above all, playing within a group – a basic aspect of the jazz experience, whatever the original channel. Others again had a mixture of backgrounds, like the player who confessed he could ‘read the dots’ but had essentially ‘learnt on the job’. Musically as well as socially, jazz musicians in Milton Keynes came from varied backgrounds.

The same complexity applied to audiences, for an interest in jazz did not appear to be the special preserve of any one section in Milton Keynes. Certainly it was not confined to a single age group and included women as well as men. ‘From babies to OAPs’ was the T-Bone Boogie Band’s boast, and this was probably the picture for other bands too, perhaps with particular emphasis on middle-aged groups. There was also the complication that some jazz clubs attracted audiences enthusiastic about one camp of jazz and unwilling to listen to others (‘trad’ as against ‘modern’ jazz in particular). Some bands, like the Original Grand Union Syncopators, Momentum or the T-Bone Boogie Band, built up their own fan groups who followed them from gig to gig and made up a large proportion of the audience when they appeared as the resident band. As with other kinds of performance, of course, such groups were probably attracted not only by the particular type of music offered but also by the company and social occasion, the dancing or talking in a pleasant atmosphere, or because of some link with the players. As one band member put it, you couldn’t expect all the audience necessarily to be ‘mad on jazz’; for another – as he explained not unappreciatively – his wife quite liked jazz, but really went along ‘to chat with the other musicians’ wives, laugh at us, and have a good chin-wag’.

Jazz in Milton Keynes, then, was more a fluid and impermanent series of bands and venues than an integrated and self-conscious musical world. There were not strong historical precursors in the area, and the local players never managed to set up a permanent venue where they could be sure of regularly hearing jazz by local and regional players over a matter of years. In addition, apart from the (general purpose) Musicians’ Union, to which few local players belonged, there was no national association to which local groups could affiliate (unlike the classical, folk, operatic and brass band worlds) – or, if there was, it was apparently of little interest to Milton Keynes players. In all, there seemed to be a less distinctive view of what ‘jazz’ was and should be than with some of the other forms of music in Milton Keynes, and the experiences of jazz players and enthusiasts were defined more by the actual activities and interactions of local bands that labelled themselves as ‘jazz’ than by any clearly articulated ideal model.

Despite this, there were shared perceptions and experiences – unformulated though these were – of what it was to be a jazz player and to play jazz. This was shown most vividly in the way jazz players, far more strikingly than rock musicians, went in for membership of more than one jazz group and moved readily between bands; it was easy to ask guests to come and jam, from named stars from outside or ex-members who happened to be around to a ten-year-old boogie-woogie pianist from the audience. For though both the form of music-making and the constitution of the groups were in a sense fluid, there were definite shared expectations about the jazz style of playing, the traditional formulae, and the modes of improvising within recognised conventions: ‘all jazz lovers know the tunes already’, as one player expressed it. Players in other groups were recognised as fellow experts – more, or less, accomplished – in the same general tradition of music-making, and bands engaged in friendly rivalry with each other, going to each other’s performances ‘to smell out the opposition’ or – on occasion – to look for a new player themselves. Similarly they were prepared to help out other bands, filling in at short notice if they were in difficulties.

Even though for practically all the players discussed here jazz was only a part-time leisure pursuit and not widely acclaimed throughout the city, both the musical activity itself, and the shared skills, pride and conventions that constituted jazz playing seemed to be a continuing element in their own identity and their perceptions of others. Once involved, ‘as a musician, you need to play … something you’ve got to do’; for, as another player put it, ‘it’s a blood thing, it’s in your veins’.