Читать книгу The Hidden Musicians - Ruth Finnegan - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPreface

This book began from my own unquestioning participation in local music, which only later turned into active curiosity. I had been involved in amateur music as both consumer and participant for many years, particularly in the town I had lived in since 1969 – Bletchley, later part of the ‘new city’ of Milton Keynes. Dwellers elsewhere were quick to label this area a ‘cultural desert’, but I myself found plenty of music going on locally.

At first, I just took this local music for granted and, beyond a vague expectation that the necessary arrangements would just be there for me and mine, did not think much about it. In any case my academic attention was in typically anthropological fashion mainly concentrated on comparative issues about oral literature and performance outside Britain. Rather late in the day I realised that what was going on around me was an equally interesting subject, linking with many of the traditional scholarly questions about the social contexts and processes of artistic activity and human relationships. There turned out too to be even more local music-making than I had at first appreciated from my own limited experience. My sensitivity to the artistic activities on my own doorstep was not much aroused by the standard works on British popular culture with their focus on sport or the mass media rather than the local arts, or by press discussion of music in terms of national professional activities or centralised funding and its problems. But eventually I began to wonder just how music was practised locally and what was the taken-for-granted system which underpinned the amateur operatic societies, brass bands, rock groups, church choirs or classical orchestras. These apparently simple questions turned out not to be much thought about or as yet the subject of very much systematic research. This study attempts to provide some answers.

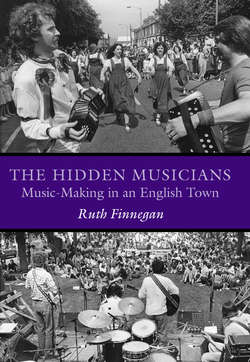

The book focusses on local music in one English town – Milton Keynes in Buckinghamshire in the early 1980s – in order to uncover the structure of the often-unrecognised practices of local music-making. Milton Keynes is not of course typical of all English towns, but it is in any event a real place which contains real people experiencing and creating musical forms which they themselves value and to which they are prepared to commit a great deal of their lives. I believe that it is a better test case for exploring the significance of local music as it is actually practised than the usual abstract or evaluative theorising.

It is easy to underestimate these grass-roots musical activities given the accepted emphasis in academic and political circles on great musical masterpieces, professional music, or famed national achievements. But for the great majority of people it is the local amateur scene that forms the setting for their active musical experience, and it is these ‘ordinary’ musicians and their activities that form the centre-piece of the study. Among them I include the untrained as well as the highly accomplished, the ‘bad’ as well as the ‘good’ performers. This partly comes from my own experience, shared with many others, that even a poor executant can take a genuine part in local music-in my case as a none-too-competent choral singer, lapsed cello player, recorder dabbler, mother of musically inclined children, and enthusiastic but musicologically unsophisticated audience member. It is also based on my conviction that amateur practitioners are just as worth investigation as professional performers, and that their cultural practices are as real and interesting as the economic or class facets of their lives to which so much attention is usually devoted.

This study is not just about Milton Keynes but also has implications for our understanding of musical – and social – practice in general, and what this means both for its participants and for wider relationships in our society. It also touches on controversial issues about the nature of popular culture, the anthropology and sociology of music, and the quality of people’s pathways in modern urban life. I hope it can lead to greater appreciation and study of what are, after all, among the most valued pursuits of our culture: the musical practices and experiences of ordinary people in their own locality, an invisible system which we usually take for granted but which upholds one vulnerable but living element of our cultural heritage.