Читать книгу The Keeper of the Kumm - Sylvia Vollenhoven - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

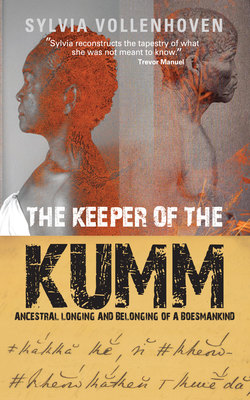

Dootje and Trina de Klerk

ОглавлениеThe mistress stood upon her. The mistress had been trampling her. I who was there, I beheld that

/Gui-an’s breath had gone. Her heart had fallen.

She was insensible.8

– /Han≠kass’o Klein Jantje

The hole in my grandmother’s head, in almost exactly the same place as a dent in my own from a childhood injury, is like a livewire connection to a vast, unspoken history. Our stories in our bodies.

About 80 years before my grandmother tells me how her head injury was inflicted, //Kabbo’s son-in-law /Han≠kass’o tells British researcher Lucy Lloyd a similar tale.

I no longer see my grandmother’s revelation as an isolated incident, something to be hidden with shame. It is part of a pattern of cruelty that has lasted for centuries and that we still have great difficulty talking about.

The 19th-century account in the Bleek-Lloyd notebooks evokes a similar intensity as the real pain in my hands when I combed Ma’s hair.

In the summer of 1879, /Han≠kass’o tells Lucy Lloyd about his grandmother /Gui-an, who they called Dootje, and her employer Trina de Klerk:

“We were sleeping in one place, one house, when my grandmother /Gui-an Dootje was ill. She could not talk. When she got better she told us that Trina de Klerk was beating her about the washing of skottelgoed.

“/Gui-an was slow washing up and Trina wanted to give food to her people. The mistress refused to wait for her. /Gui-an could not see nicely. She dried the dishes slowly, packing one thing on top of another carefully. One time she worked quickly and a cup broke. She was beaten and since that day could not see properly. She was afraid it could happen again on account of her eyes.

“/Gui-an Dootje told me the mistress stood upon her, the mistress was trampling her. She became insensible. Then she arose while she was still warm and came home. When the wind was cold she became cool. She became insensible again. We lifted her up. We put her in the house. The place became dark and she lay there. She could not breathe.

“Trina de Klerk said /Gui-an Dootje did not want to work, she was laying there from laziness. I who was there, I saw that /Gui-an’s breath had gone. Her heart had fallen. She was insensible. She did not breathe. When the place was night she recovered her breath.”

In the wheat-farming district in the Overberg, where my grandmother was born, stories of white farmers or the police attacking black people abound.

In Swellendam, where the national highway divides the bodorp and onderdorp, segregating the town along racial lines, this cruelty is treated as the norm. During school holidays we go there and the tension when we walk in the white part of town is palpable.

As a young journalist, I write about the attack on my grandmother for a magazine. The descendants of Oubaas Streicher get to read it. They phone my mother and invite us to the farm. My grandmother is not happy that I have embarrassed the Streicher family in this way.

My mother Eileen is the only one eager to make the trip to Swellendam to drink tea with the modern Streichers. For a long time we talk about it, making half-hearted plans. When we finally take up the offer, it is a tense affair with the Streichers eager to show my mother and I the cottage where Ma was born. When we leave they give us a book about their family history.

Nobody refers to the beating that I’ve written about in the magazine.