Читать книгу The Keeper of the Kumm - Sylvia Vollenhoven - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

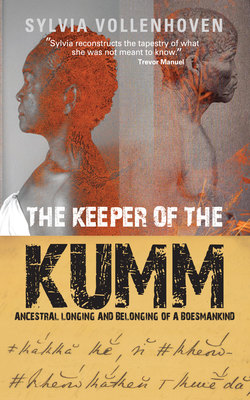

Longing and belonging

ОглавлениеThe girl follows the spoor of an old story animal. In the fading light she cannot see but the wind of its passing lifts the hem of her attention.

My grandmother lives to be almost a hundred years old and for most of her life the flu epidemic of 1918 is her only experience of serious illness. But a sickness that tugs at her heart is her longing for Swellendam, the place of her birth. She says homesickness is a disease of the soul.

“As ’n mens so sielsiek is kan niks en niemand jou red nie.”

I know each year when Christmas is getting closer because Ma starts talking non-stop about Swellendam. When I am in primary school, I help her write letters to her only relative who has children who can read. None of Ma’s brothers and sisters went to school. But her sister Auntie Rachel, who lives in Die Dam, as my family calls the Overberg town where the Petersens and Vollenhovens come from, has educated, grown-up children. Her daughters Sienie and Leen are the ones who can read the letters I write on the Croxley notepaper that we buy at Mr Brey’s shop when Ma gets her pension.

“Skryf daar vir jou Auntie Ragel, ‘All is well this side with Eileen, Freddie and the children. How are things with you? Sy hou tog so daarvan dat ons vir haar in Engels skryf.”

Dearest Aunty Ray, we are writing to tell you that all is well with us. We are hoping to hear the same from you. We are planning to come to Swellendam for the festive season and hope this will be in order.

Just a few sentences and my thin-up, thick-down cursive strokes fill the page. The style is straight out of my English lessons. I feel like I am writing to the white people in the books I read at school. There is no place for sharing intimacies in this kind of language but Ma claps her hands with pride when I read it back to her. When the letter arrives at Auntie Rachel’s in Treu Street, Railton, it is propped up behind the glass in the dining room display cabinet to be taken out occasionally for envious neighbours. I doubt whether anyone actually reads it.

“Wake up, Sylvia, we’ll be there any minute now. Here, have some tea.” Ma holds out a Thermos flask with her favourite rooibos herbal drink. On the train to Swellendam we eat breakfast – cream crackers and cheese – from a round cake tin with pictures of proteas on the lid.

The train crosses the Breede River. Soon it is alongside the highway that divides the white bodorp in the shade of the Langeberg from the black onderdorp township of Railton. A collection of matchbox houses sweltering in a treeless expanse on a road to nowhere.

There are many people at the station. Ma struggles with the luggage. The platform is just long enough to service the front end of the train, where white people sit. They step easily onto the platform while we negotiate the long drop from the train to the ground. From where I am standing next to my grandmother I look at the legs of the white people. Pale stockings and grey trousers moving confidently way above us. We wait until they have left the station and then move onto the platform towards the station exit. Nobody tells us to wait, we just do.

I love being in Swellendam. When my grandmother is with her family, they drift between worlds, visible and invisible. The stories jump around like children on a trampoline and I run around trying to catch the threads.

Ma’s family are descendants of the indigenous people, the Khoi and San, and imported slaves. But nobody ever talks about this heritage or the fact that there might be colonial and especially Afrikaner blood running in our veins.

Her brother Oomie Abraham has a pet name for everyone. My Auntie Rachel is Ousus, Ma is Tietie and he calls me moerkoffie. When it comes to his affections, I run a close second to his favourite farm brew. I am very young when I notice that he can’t do without his coffee. So when my aunt asks me one day what I would like, I point to Oomie Abraham and say confidently, “Strong coffee”. So now whenever we arrive from Cape Town he comes out onto the werf in front of their whitewashed farm cottage, holds his arms wide open and says: “Hier kom my strong coffee.” His rolling brogue makes each word sound intimate and warm.

In winter, Swellendam is very cold so we hardly ever go during the mid-year school holidays. In mid-summer, the Overberg is a swirl of red earth, yellow harvested wheat fields, brown haystacks and flowering fynbos. Sunlit sheep hardly move in the heat. The Langeberg mountains sing blue praises all along the edges of this tableau.

Ma is the youngest of her siblings. She had a younger brother but he died in a thunderstorm, struck by lightning when she was left to take care of him in the fields. There is always a blue crocheted baby’s bonnet in her wardrobe. My mother says it’s what her brother was wearing that day as they sheltered from the storm. Ma says it has never been worn because it was intended for a baby boy she miscarried. But whatever it is, it’s her secret albatross and each time we move house she takes it along.

Swellendam is the centre of our world. We are happier here than anywhere else.

Whenever Ma arrives in Swellendam she goes to visit her brother Oomie Abraham first. Then, because the thatch-roofed cottage in Waaihoek in the foothills of the Langeberg is too small for visitors, we make our way down into the valley and across the railway line to her sister Rachel’s house in Railton.

In the Petersen family, Rachel Pekeur is a wealthy woman, although nobody ever talks about the source of her relative abundance. I assume it’s because she married a school principal, Oom Japie Pekeur, and is a cook at the Royal Hotel in the main street.

The people of Swellendam are descended from the great Hessequa or People of the Trees, the indigenous Khoikhoi who the colonials called Hottentots, the San (who today prefer to be known as Bushmen), the slaves who came from the East and other parts of Africa and, of course, from European colonials.

Fair-skinned Auntie Rachel with eyes coloured in a cognac amber has long, curly black hair and is living proof of the complex relationships between the wealthy white folk on the slopes of the mountain, Afrikaners with Dutch ancestry, and the people of the black downtown onderdorp.

Ma attends the Seventh-day Adventist church in the city but here she resorts to the only option, a dour dominee with an unyielding white tie and ‘God help julle’ manel coat.

The dominee’s admonitions come with a hefty fist slammed onto the pulpit. Having worked himself into a frenzy to wake a gently dozing congregation, the dominee says things like:

“En dan sal dit te laat wees om te skree, ‘Vader vergewe ons’, want julle’t een keer te veel met die duiwel gedans en sy musiek het julle gelei tot die deure van die verdoemenis.”

When he finally announces the closing hymn, even my devout grandmother seems relieved that the harangue has ended for now. Afterwards the adults say their goodbyes and catch up with the events of the district outside the church. The children loosen their clothing and make plans for elaborate games in the foothills of the mountains.

“Can I go with them, please?” I ask, tugging at the sleeve of Ma’s twinset.

I give up getting my grandmother’s attention as she and Auntie Rachel talk away with the dominee and slip away with my cousins. Ballie, the ringleader, takes us down the gravel road, across the railway, past the white people’s houses and through deep dongas to get to his favourite places in the Langeberg foothills.

“Up there near Waaihoek there is a hut that belongs to the bosbou people who use it during the week.”

Soon we’re on a farm where the district’s legendary youngberries grow wild. We attack the youngberry bushes with relish. Our hands find the shortest route to our mouths, heads buried in the foliage. Some berries are overripe, almost black. Sweet bubbles of pure sunshine explode between my teeth. Others are still bright red and I almost cry with delight as the tart taste tugs at my tongue.

“Jissie, Sylvia, kyk jou rok,” says Ballie.

My grey and pink nylon frock with the embossed silk flowers has assumed a drastically different colour scheme.

“Jou ouma gaan jou moer,” says Ballie laughing.

Where I’ve grown up, side by side with my grandmother in the genteel kitchens of rich, English-speaking white folk, words like moer are entirely absent. Ballie is eager to show off his grown-up language.

“That’s okay,” I say, “I’ll take Ma some and she’ll be happy.”

The children around me are awed because I can speak English.

“Hei Sylvia,” says Ballie, stopping to show off a bit, “praat Engels vir ons.”

It is a constant request. Few people in Swellendam use English and outside of the classroom the children hardly ever hear it spoken. There are hardly any books or newspapers and on the radio everything is in Afrikaans. Ballie likes having a cousin who makes the other kids sit up and take notice.

“Kom Sylvia, spoeg vissies9,” he says, laughing.

“Baa, baa, black sheep, have you any wool?” I begin in my best accent, reflecting the combined influences of white neighbourhoods and my mother’s years of elocution lessons with Irish nuns.

Nobody understands a word I’m saying. The children laugh and clap their hands, asking for more until Ballie gets bored with the adoration. We head off further into the forest.

Inside the bosbou hut they start an elaborate game of house or huisie-huisie. As usual, I am the baby in the game. My older cousins, Siena and Leen, are our parents. Ballie and his friends are the children. English cabaret over, I’m automatically sidelined.

The children go off to ‘work’ with instructions to bring back food to eat. It’s Ballie’s favourite game and his licence to raid the surrounding farms and kill pigeons.

“En toe sê daai skollie vir Mary, ‘Ek sal jou naai tot die bloed loop,’ en sy hardloop toe daar weg.”

Sienie and Leen are gossiping while I pretend to be playing a game of pick-up stones with some round river pebbles. I’m glued to the adult words coming out of their mouths as they discuss the latest village scandal.

On the way home one of the notorious child gangs from Lemmetjiesdorp stops us. It is the usual ritual. First they trade rich insults, then the boys start shoving each other until there is a fight that everyone can cheer.

“Kom jy wat Ballie is, staan jou man.”

Ballie is slow to respond. The boy challenging him is older and tougher. To buy time Ballie takes off his shirt, slowly. I am blissfully unaware of the order of things but I feel left out. So I shout an insult I’ve just heard. In my naïve mind the Afrikaans means purely, “I will stitch you up until you bleed”.

“Ek sal jou naai tot die bloed loop,” I shout loudly at the opposing group. Most of them have not noticed me until this moment. All aggression stops. They stare at the skinny eight-year-old in the stained nylon dress with giant pink bows on her thick plaits that jut out Pippie Langkous10 style.

Not even the rough youngsters of Lemmetjiesdorp have heard a girl say such a filthy thing. My older cousins Sienie and Leen look vaguely guilty but sense the odd advantage this has given us. It is not often that kids from Railton muster up a surprise tactic in an encounter with a Lemmetjiesdorp crowd.

While the opponents are gobsmacked, my cousins saunter off. Ballie looks at me with absolute horror but he recovers quickly. He turns to shout at the little group we are leaving behind:

“Sy’s vannie Kaap en sy kan dit in Engels ook sê.”

I feel victorious but at the same time there is an uneasy sensation in my stomach. It gets worse as Ballie shoots off ahead shouting; “Ek gaan vir Ta’ Sofie sê.”

We walk home quietly and I know that whatever just happened is not good. As we reach Auntie Rachel’s house in Railton, Ballie is pouring out the story to a group of adults with arms flying.

“En toe sê Sylvia, ekskuus tog, Mamma-hulle. Ek sal jou naai tot die bloed loop.”

From a distance I see my grandmother go inside the house. She reappears with the long leather strap she uses to hold her suitcase together. It is twisted around her left hand.

When adults attack young children, many emotions fly around … anger, disappointment and sometimes enjoyment. Sophia Petersen, who has never before dished out a hiding to anyone, is sad and overcome with embarrassment.

Nobody says anything about the swearing. They pretend it is the stained Sunday dress that is the major cause of the punishment. The adults have neither the words nor the courage to respond to me having told some roughnecks I would fuck them until they bled.

My sobs are more for the pain in my insides than for the welts rising on my legs. A defiant sadness settles in my soul and in the days that follow I cannot dislodge it no matter how hard I try.

When innocence goes as it always does, it leaves softly, steps out lightly. And in its place is an open space, a well of sadness that points us home but has no name.

When I grow older, my childhood in Swellendam becomes those halcyon days, more magical with each recollection. It is an inner refuge when things become too difficult. A place where I can still smell the leather bridle of the kapkar buggy, Auntie Rachel’s famed ginger beer and Oomie Abraham’s strong moerkoffie.

One day when I’m doing an SABC outside broadcast in Swellendam, I meet the town’s first black mayor.

“I have named a road here after you. A section of the street where I live,” he says casually.

I look it up and sure enough, there it is. A tiny section of the Ringstraat that I know and that is around the corner from Treustraat where my Auntie Rachel lived is now called Vollenhoven Street. A piece of Google Maps reality with my stepfather’s family name.

After the broadcast, I return to the Overberg on my own. But I discover that my longing all this time is not for Swellendam. It is for a place that is more me than any other in which I have lived. It is for a place where my ancestors lie buried. It is for a place I have yet to find.