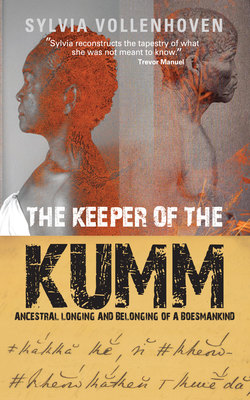

Читать книгу The Keeper of the Kumm - Sylvia Vollenhoven - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

My husband is fighting for king and country

ОглавлениеAt night the Guardians sing the songs of The Calling by the fire. Strains that dissipate when they cross the great river.

“Ophou my so baie goed vra. My kop is soms so deurmekanner ek weet nie of ek kom of gaan nie.”

“Mama, it’s very simple. When was Ma born? Where is Ma’s birth certificate?”

“Haai, raai ek het nou vir jou skool toe loop stuur sodat jy vir my kan kom cross-question soos ’n wafferse magistraat. Ek hou ga van kinners wat vir hulle so ouderwets staan en gedra nie.”

“But why can’t Mama just tell me?”

“Ag Sylviatjie, los my vandag net uit. My kop draai. Seker maar die hoë bloed. Ek kan nie so baie vrae antwoord nie. Die goed wat jy darem kwytraak.”

“But it’s just one question …”

“Heitsa! Gaan speel buitenkant. Jy sit nou net te veel met daai klomp boeke van jou. Gaan speel met die anner kinners in die son bietjie.”

Some days I get long stories and endless answers to my questions and other days Ma looks like she’s in pain when I ask her things about our ancestry. The question about her birth date never ever gets an answer. If I want to stay with Ma here in the kitchen where a meaty brown stew is simmering on the twin wicks of the Beatrice stove, I have to change the subject.

I love the way Ma jumps around from one thing to the next when she tells stories. Often she leaps up from the table in the kitchen where we always sit and plays the characters. One minute she’s a stiff Oubaas Streicher praying in Dutch – Hooghollands – and the next she’s doing her best imitation of maudlin, drunk Auntie Bettie at Christmas time.

“Nou, Ou Dollie, Oom Dawid se vrou, het mos so ’n wipstappie gehad. Sy swaai daai heupe en lokke van haar en vertel ons hoe niemand in ons familie gladde hare het nie. Dan dink ek maar by myself: ‘Ai, ou Sofie mens, sit liewers met ’n kroeskop as om met sulke olierige toiings rond te loop.’”

With her hair tightly braided – two plaits pinned down in front and two at the back – Ma does a little twirl in the middle of the kitchen, shaking imaginary locks out of the way. Her bum follows a gentle arc as she looks over her shoulder at me. She becomes my untidy Auntie Dollie with the greasy hair. She would much rather entertain me than tackle the pile of sour-smelling clothes in the rickety wooden laundry cupboard or scrub the pots until you can see your face.

“Nou staan sy daar by die government kantoor en Oom Dawid is in Egipte. Sy wil glad nie in ’n queue staan nie so sy skree bo almal se koppe vir die man agter die tralies van die toonbank. ‘My husband is fighting for king and country.’11 Die Engels kom ook glad nie so lekker uit nie. Verbeel jou! Sy ga’ aan oor kung en kindtree en niemand ka’ uitmaak wat sy sê nie.

“Haar kinners Sylvie en June en Stephen is in hulle beste klere daar saam met haar. Maar die wit man maak of hy haar glad nie hoor nie. Ek dink Broer Dawid het geloop oorlog toe want hy kon haar geskree nie meer verdra nie. En met daai taai hare was sy darem vir jou slordig. Dan’s sy nog so lief gewees vir pure wit blamanch pudding maak.”

The Auntie Dollie story morphs into the story about minstrels at Hartleyvale and before I know it we’re talking about how much she longs for Swellendam and the Langeberg mountains.

But everything comes to a standstill when Springbok Radio plays the violin tune that signals the start of her daily serial. “‘Die Indringer’, deur Dricky Beukes,”12 says a deep male voice. We say the tagline along with the announcer:

“’n Verhaal wat elke moederhart sal roer.”

We listen in absolute silence to the story about the struggles of a stepchild, alienated by her adopted family. Sometimes we both cry.

“Is it too much to ask that the food should be done when we get home from work?!”

When my mother comes home from the clothing factory, we have to step out of our world and make sure that the house is shipshape. When Freddie, my stepfather, follows soon after, the house becomes even quieter. It is a completely different place compared to the one where Auntie Dollie did pirouettes with Oubaas Streicher and the radio serial drifted across a simmering stew on the little Beatrice stove.

“Alewig die ou stories. Die Here hou nie daarvan dat ’n mens so voor ’n radio sit en stories luister nie.”

My mother blames the radio soapies for the supper not being prepared on time.

“We are going to spend an eternity with our Father in Heaven listening to stories,” is my grandmother’s stock reply to my mother’s accusations that neglecting the housework in favour of Dricky Beukes and Die Indringer is ungodly. When my grandmother talks about the hereafter or anything vaguely connected to the book of Revelations in the Bible, she prefers English. The Second Coming is not an Afrikaans topic.

“Jy gaan my mis soos ’n stukkie brood die dag as ek nie meer daar is nie.”

Ma talking about her death always sends my mother into a quiet retreat so that Ma can get on with the supper.

“Stories staan mos nou nie stil vir ons staan en wag nie. Hy loop aan en as jy nie byhou nie verloor jy hom.”

My grandmother thinks that it is fitting that stories rule our lives. She has an intense interest in everything I learn at school. Vicariously she laps up the details about history and faraway places. My English and Afrikaans storybooks captivate her attention more than anything else.

She knows so much about what is happening in the world that I’m shocked when I learn she’s never been to school. When she refuses to tell me about my grandparents and our family history, I imagine unspeakable skeletons in the family closet. It takes me many years to accept that my story-loving grandmother does not know the most important narrative of all. Who am I?

“Die oumense het ons kinders niks vertel nie,” she says.

A teacher I meet when I am older tells me: “My great grandmother says our people stopped talking about their history because of the pain. So much dying and violence. It became a taboo to tell children about the past. They became embarrassed to pass on stories about so much loss.”

One summer day stands out for me because Ma seems afraid and is even more reluctant than usual to answer my questions.

There is a strange quiet in the township. There are fewer children on the streets and our school gates have been locked. This has never happened before.

When I get home, I put my yellow plastic lunch box and blue enamel mug in the sink as usual, while telling my grandmother about the locked gates.

“Why were there so many black people marching past our school today?”

Silence.

She pulls at the woven belt of my gymslip with the long tassel dangling beyond the reaches of my hem.

“Careful, you’re always getting this thing into a knot.”

I persist.

“During break we saw many Africans marching down the road. The teachers told us not to stand too close to the fence.”

Close to our school there are several squatter settlements where black people live. Never before have I seen people who don’t live in our neighbourhood walking through here. We never go to the squatter camp even though it is just on the other side of the Prince George Drive main road.

“Die swart mense is ontevrede met die regering … en nee, ek weet nie hoekom nie,” says my grandmother before fiddling with the knobs on the radiogram in the lounge.

In the ’70s, when I am researching a story for The Cape Herald newspaper, I finally find out why people were marching. I read about the anti-pass law campaign that led to the fatal shootings at Sharpeville and the arrest of many. I read about a young leader called Philip Kgosana who took the Cape Town police by surprise when he led a march of about 20 000 people on 30 March 1960. They had come from every part of the Peninsula and a small phalanx had come past my school. I was in Sub B (Grade 2).

My grandmother’s stories sustain me but they have huge gaps, starting with the details of our own history. Nowhere in my upbringing does anyone offer a story of who we are as the descendants of the First Nations. Her obsession with stories on the radio and in my schoolbooks had to fill that huge void.

“Why don’t you go to the church in the district where your grandmother was born?” a newspaper colleague asks years later.

In the absence of even a birth certificate, it took my mother and the social workers five years of detective work just to scrape enough information together for my granny’s old age pension application. I can’t see the usefulness of going down the road the white journalist suggests.

Apart from the anecdotes of life in Swellendam and my uncle who ‘fought for king and country’ in World War II, the family history that has come my way would fit on a napkin.