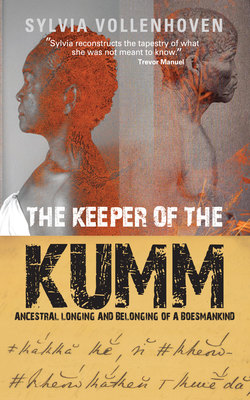

Читать книгу The Keeper of the Kumm - Sylvia Vollenhoven - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

White parks and pressure cookers

ОглавлениеThe spirit of the sea and the blue mystery of the mountains hold her hand. Together they wait.

The Davids family of Privet Villa are warm and comforting people. Auntie Gracie and her daughters comb my hair and let me sit on their laps, even when I’m almost too big for it. Uncle Willy, Auntie Gracie’s husband, works long hours but if I wait for him, especially in the summer evenings, at the low stone wall on the corner of the school in Ottery Road, he stops his huge black bicycle. He gets off so that I can sit on the saddle, perched high above the road. Then he gently wheels his cycle down towards the house, pretending that I’m fully in charge.

At the Vollenhovens’ house, Shalom, I feel only discomfort and strangeness. Nobody touches anybody here. I imagine my mother must feel out of place too and that she will come back to us so that we can hug her when the stew-mountain gobblers spit her out.

My grandmother and I now live in servants’ quarters at the home of the Sonneveld family. The name of the house, Alma, perches above the driveway gate in curly pink wrought-iron lettering.

At Alma it is even more cold and forbidding than at Shalom. When the Sonnevelds are out and Ma is done with her cleaning up, it looks like nobody lives in the large rooms with the dark wooden floors.

Ma likes people to call her a ‘cook general’ and says she is ‘nobody’s servant’. Our cement-floored room has a separate entrance to the main house and is very different to the rickety shack at Privet Villa.

Ma says a ‘sleep-in cook general’ for foreign people is the best job in Cape Town.

“Jy weet waar jy staan met ’n boer. Straightforward mense, maar hulle betaal nie. Die Engelse is agterbaks en die Jode is suinig.”

Her thumbnail sketches of Cape Town’s white people become my own rough guide. I am young but I understand that we are a level above the women in the neighbourhood who work for problematic South African madams.

Ma always sings hymns when she works. Sometimes when she sings or talks about God she cries.

“Die liefde van Jesus is wonderbaar, wonderbaar, prys sy naam …”

She’s singing and crying, looking out of the window. So I cry too.

“My gemoed slaan so vol van die Here se genade,” she tells me.

But a summons from the madam has the ability to change Ma’s mood in an instant.

“Sofie,” calls Mrs Sonneveld from the kitchen steps across the yard, “Alma has some old clothes for Sylvia. Alma, go and show Sylvia the box.”

Alma, the Sonneveld’s only child, is a bit older than me and much taller. She takes me by the hand into the yard to a small cardboard box full of clothes. The clothes smell like her blonde hair.

“They’re too small for me. My mamma says they will fit you. My pappa bought this one in Amsterdam.”

Alma is pulling outfits out of the box and holding up dresses, blouses, underwear, bonnets and socks. The Sonneveld family arrived in South Africa recently. Alma has shoes that look like wooden boats. Some of the clothes look strange. A blue felt outfit has a bright orange pattern and a pointy hat that makes me look like a goblin.

“Don’t worry,” says Ma with her usual insight, “I’ll make it smaller for you.”

Later, when we are alone in the room, she says;

“Ma kan sien jy hou nie van die mense se Hollandse klere nie. Toe maar, ek sal vir haar sê jy gaan dit naweke dra as ons huistoe gaan. Ons mag arm wees maar ons dra nie wit mense se ou klere nie.”

Whenever I look at the box of undisturbed Dutch clothes under the small bed we share in the servant’s quarters, I feel proud and very close to my granny. A while later Mrs Sonneveld buys me a brand new outfit, just like her daughter’s. Nobody says anything ever again about the old clothes.

Ma works in the house cooking and cleaning till late at night. Sometimes Alma plays with me but most of the time I’m alone in the garden with my toys. I miss Claudie more than anyone else in Brentwood Road.

“Come inside and stop talking to yourself so much. Here, get onto this chair and help me with the washing up. Try not to get yourself so wet this time.”

“I’m talking to my dolls,” I say.

We don’t have a bathroom and we are not allowed to use those in the house. Ma fills a big zinc bath with water she has boiled in the kitchen and we wash late at night when no one can see us out in the yard.

“I want to brush my teeth with Sylvia!”

Because I use the garden tap in the mornings and Alma likes the big white splashes I make on the neat green lawn, she refuses to use the bathroom inside. We spit white toothpaste pictures onto the green lawn.

Sometimes when Mr Sonneveld is at work and Alma goes out with her mother, my granny and I take turns washing in their huge bathroom.

“When you see them coming, run to tell me.”

I stand watch while my granny washes and she does the same for me. One day she is washing my hair when we hear Mrs Sonneveld’s car pulling into the driveway.

“Tel op jou borsel. Maak gou! Vat alles agter toe.”

My dress is soaked with water from my thick hair streaming down my back but we manage to clear all the evidence from the bathroom before Mrs Sonneveld calls my granny to help her carry the groceries.

“Sylvia, Penny is going to take us to the park,” says Alma.

Penny is the nanny who looks after the girl next door. She walks us down from the Sonneveld house in Woodley Road to the nearby Basil Road Park a few streets away. She puts us all on a row of swings and pushes us one by one until everyone is flying high and screaming nervously.

Basil Road Park is full of Plumstead’s white children and nannies who come from Wynberg. The nannies are almost all dark-skinned like me and Ma. The fair-skinned coloureds of Wynberg don’t work for white people.

I love the bright red and yellow swings on their green poles. The roundabout makes me throw up so we keep away from that. When we’re done with the swings, we take turns on the seesaw with the wooden seats and horse-head handles.

“Come on, Sylvia, follow Alma and Lucy to the top,” says Penny, standing next to the jungle gym.

I pull myself up one level and then, looking down, I see a group of boys behind Penny.

“Alma plays with kaffirs. Alma plays with kaffirs.”

Penny turns around waving her hand at them threateningly. I can see Penny is nervous. She is about 12 years old and the boys are big. A woman who has been sitting on one of the park benches comes over. I feel relieved. She’ll tell them to go away, I think.

“That child is not allowed to play here. This park is only for white children. Take her out of here.”

None of what the woman is saying makes sense but it’s clear that she’s not on our side. Penny lifts me off the jungle gym.

“Come, we’re going home.”

At the Sonneveld house in Woodley Road I run down the driveway hoping to find my granny and an explanation.

“Ma, Ma there are big boys in the park. They say …”

Ma comes out of the kitchen, holding a large spoon.

“Shush, stop shouting. Calm down. What’s wrong?”

“Penny, you tell her.”

I have no words for what just happened.

“Auntie, daai boere jongens wat so moeilikheid maak het lelike goed vir Alma geskree. Toe kom ’n vrou, ek ken haar nie. Ek dink sy gaan hulle stop, maar sy sê toe die park is net vir wit mense.”

My grandmother is a placid woman whose passion is reserved for her religious pursuits. I have never seen such an angry expression on her face. I look up. But before she can respond a loud explosion comes from the kitchen.

The white walls and ceiling of the Sonneveld kitchen are sprayed with green pea soup. It’s my grandmother’s introduction to the hazards of pressure cookers.

“These things always happen in threes,” says my Granny and tells Penny about almost being caught in the bathroom that morning. “Now those hooligans, and I’ll probably get sacked for that kitchen mess.”

Ma finishes cooking the supper but she is very quiet.

“I explained to you so many times how it works, Sofie.”

Mrs Sonneveld is the only adult who calls my grandmother by her first name. It sounds naked on its own like that. To everyone else she is “Auntie Sofie” or “Mrs Petersen” and “Sister” to her siblings and her Seventh-day Adventist congregation.

Mrs Sonneveld is angry. Her face is red and she shouts about taking money from Ma’s pay for things to be fixed. Ma slowly unties the strings of her white apron. She folds it and hangs it over one of the kitchen chairs.

“I’m going to my room, Madam. I won’t be long. When I come back, I’ll clean the kitchen and finish your supper.”

As she walks across the yard to our room, Mrs Sonneveld is still shouting.

“Come back here! Who told you you could leave? You’ll have to explain to the master!”

After a while she follows Ma across the garden. Her fine white shoes tread carefully around the garden hose and rubbish bins. She walks as if she’s never been to this part of the property before. She pulls open the door but when she sees Ma kneeling next to the bed with her head on her folded hands, she walks back to the kitchen mumbling.

When we settle down to life with the Sonnevelds in Plumstead, my world becomes our separate entrance, the kitchen at Alma and weekends that are all too brief in Brentwood Road or at church.

There is a dream that comes to comfort me often. I am walking along the Wynberg streets and I come across a group of huge, very pink beings. They don’t look like humans but yet they are familiar. It seems as if they are waiting for me to come along.

When they pick me up a glow of pure pleasure spreads like liquid laughter through me. One by one they hold me up to the sun that shines warmly on my already glowing skin. It becomes so bright that it dazzles me awake. It always takes a while for the delicious sensation of the touch of the huge pink entities and the warm sunlight to subside. And when the feeling fades, I feel so sad I want to cry.

“I dreamed about sitting with angels in the sunshine on the stoep of Mr Brey’s shop in Ottery Road. They picked me up and we played. The angels rocked me one by one. Then they showed me how to fly. I miss my mummy and Auntie Gracie. Can we go back?” I tell Ma tearfully in the morning.

“Die Here het vir jou gestuur. Die Bybel sê die Here sal met die klein kinders praat sodat ons kan hoor,” says my grandmother, picking me up and holding me very, very tightly.

She always makes me tell her every detail of my dreams, especially the ones with the pink angels. Sometimes I dream about Jesus but she won’t allow me to talk about this.

“Moet vir niemand hiervan sê nie. Mense verstaan nie altyd dié goed so mooi nie.”

I don’t know what she means but it feels good to sink into her Cuticura soap and 4711 Eau de Cologne warmth while she sings her favourite chorus.

Blessed Assurance, Jesus is mine!

Oh, what a foretaste of glory divine …

The world of the Vollenhovens or white parks and pressure cookers is very far away when we are together like this. Even when I am away from my grandmother I can still smell and feel her close by, still hear her singing.

My grandmother Sophia Petersen is my centre of belonging.