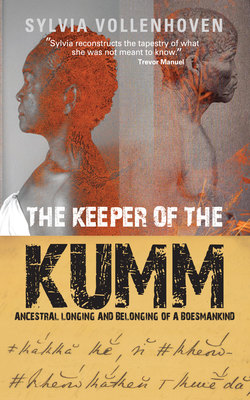

Читать книгу The Keeper of the Kumm - Sylvia Vollenhoven - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Ougat vs kaffirtjie

ОглавлениеA whirlwind of dreams pushes some of the travellers into the holes they are digging.

At a time when Philip Kgosana faced arrest, then jail and later exile, my primary school hours were dominated by more immediate concerns. On a lazy autumn day, a note torn out of an exercise book lands on my desk. It is a letter from Lavona smuggled across the class while Miss McGregor tells Janet and John stories.

“Dear Dough Nose, we have decided that we can’t play with you because you have a dough nose. Lavona, Sandra, Hazel and Valda.”

As I read the note passed along surreptitiously, I hear the giggles from the almost-white girls. The words ‘dough nose’ explode in my head like a knockout blow in a boxing ring. The ache is made worse by the fact that I refuse to cry or show any emotion. It all sits in my throat and stomach. The girls assume I am unperturbed so they add a few other insults in the playground.

“Kaffirtjie, go play with your kaffirtjie friend,” says one, referring to Karen, the only other dark-skinned girl in the class.

“You can’t be a princess. You have a kroeskop,” says another when the school play dominates the classroom chatter.

When the curtain goes up, Karen and I are frogs perched like green polyester statues on papier-mâché lily pads stage right. Lavona, Sandra and the almost-white cluster are fairies, princes and princesses singing and dancing in diaphanous blue centre stage, in a tale I don’t much understand.

For many years that particular brand of suppressed anger, embarrassment and pain pendulums on the periphery of my existence like a rogue wrecking ball, waiting to pulverise anything at all of value that I might create.

But despite the rough stuff, I love going to school and wearing a uniform. At the beginning of each year, I read all the books we are given in the first week so that I have plenty of time to play.

Then comes the year of the violent encounter with Sandra, the only girl in Standard 2 (Grade 4) who has already started growing breasts. We are playing ‘pick up stones’ when Sandra, who has repeated a couple of grades already, says;

“So, where do babies come from?”

The other girls like Sandra because she has long blonde plaits and blue eyes.

“Oh, that’s easy,” I say, falling into the trap. Solemnly I repeat the shaved baboon theory I heard from a friend. Sandra’s yellow fringe bobs up and down on her pink face as she leads the chorus of laughter.

“And that’s why babies have blue marks on their bums!” I say emphatically, despite the laughter and the eye-rolling.

Sandra, much older than the rest of us, is accustomed to being the respected authority.

“What nonsense,” says Sandra, waving her pudgy palms around.

Of course she knows better. Not because she’s precocious or ougat as they say on the Cape Flats. Bored with her schoolwork, she’s already reading her brother’s magazines. Sandra lives in Heathfield where the coloured people own their homes and can’t speak a word of Afrikaans. She has everything it takes to place her on the right side of the credibility gap at Central Primary School.

Shunned by real whites and avoiding any contact with dark-skinned coloured people, the almost-white families of Cape Town’s almost-white suburbs protect fragile identities with coded behaviour that takes me years to decipher.

The almost-white headmaster of Central Primary School, Mr Henkel, and his almost-white teachers accept me and other dark-skinned, curly-haired kids grudgingly. Fay van Niekerk is as black as I am but she at least has long Indian hair, so she’s not part of our clique of kroeskop rebels. Nobody discusses the school’s admission’s policy. It is just accepted and I learn how to behave as a member of this underprivileged minority.

By the time Sandra has finished spitting out her version of the secrets of procreation – mostly in the language of her brother’s magazines – I am traumatised and confounded. But I say bravely: “Oh, I knew that. It’s just that I was told I’m not supposed to tell anybody else.”

The heat of the lie makes my uniform shrink and choke me but I imagine I see at least a bit of doubt on the faces of Sandra and her friends. I envy the way their ribbons often slip off their hair. I secretly admire the languid gesture of picking up a ribbon and tying it back onto the end of a plait, while conversation continues uninterrupted. Utter sophistication. My grandmother braids my ribbons into my hair. A missing ribbon is a significant economic setback. My curly hair takes care of the rest of the demands of ribbon preservation.

“If you knew,” says her Pudgy Pinkness, “then tell me this …”

I feel a little muscle in my neck play tug rope with my struggling smile.

“Tell me why …” She draws out the question with an ougat tilt of her head. Sandra revels in the adoring looks from her gang.

“When do you get your periods?”

I sink further into a quagmire of lies.

“I got it but I just didn’t tell you. My mother told me not to tell anyone, especially the boys.”

A conversation I once overheard between my mother and Auntie Gracie’s daughter, Ursula, suddenly slides into place, like a roulette ball finding its snug hollow. Sandra’s interest in my story wanes in direct proportion to my growing confidence.

“Okay, let’s carry on playing. I’m winning anyway, kaffirtjie!”

The clanging brass bell that signals the end of interval forces me to shelve my explosion of anger. During the final lesson of the day, Karen and I have a whispered conversation about how to put an end to the kaffirtjie nickname. Being called a kaffir is at the top of the list of insults for dark-skinned coloured kids. It is right up there alongside Boesman or hotnot. Name-calling I rail against all through my childhood.

With my school years behind me, the fight continues within myself. Our black ancestry, especially references to our forefathers the Bushmen or San and Khoi, is never ever acknowledged, not even in the safety of our own homes.

One of the Central Primary School teachers, Miss McGregor, takes us to the museum in Gardens and I stare at the dioramas that depict San people problematically in the same disconnected way that I stare at the dinosaur exhibit. Nothing to do with me.

In the Central playground, in a sandy patch on the edge of the tarmac, we play high jump with a length of rope held by fat girls or juniors who jump at the privilege of playing with kids a grade older. Sometimes David, who is very camp, rushes to hold the rope because it’s an escape from getting his uniform dirty in the games with the boys.

Karen and I are playing in the patch of sand. She has taught me how to trip kids mid-stride, from behind. Sandra is walking away from the rope she has just cleared easily. At the right pace I go up behind her and stick my right leg between hers. She floors like Bernard did in the practice run. When she rolls over onto her back I descend, pulling her specs off and throwing sand into her eyes with a couple of easy moves.

Karen has convinced me that all is fair when your opponent has a size advantage. Reeling from the surprise attack, Sandra offers no resistance. I sit on her chest and pummel her until she starts screaming.

“Who’s your kaffirtjie?” shouts Karen, standing proudly on the sidelines.

The unwritten code in Standard 2 is that you only complain to the teacher if you’re bleeding. It’s babyish to report anything less and a wounded ego doesn’t count as serious injury.

But I didn’t bargain on one of the girls telling her mother. On Saturday morning after church, Lavona’s mother gives my mother a graphic account of the whole affair with a few swear words that I haven’t mastered yet thrown into the mix.

My mother is skaamkwaad, that dangerous mixture of embarrassed and angry.

Seventh-day Adventists are not allowed to punish their children on the Sabbath. During the long wait until sunset on Saturday when all worldly things can be resumed, I comfort myself with my newfound heroine status at Central Primary.

“Jy moet maar jou lyf solank vet smeer, meisiekind. Waar het jy daai vuil maniere, sulke lelike taal opgetel?”

My grandmother’s suggestion of rubbing fat onto your body in preparation for a beating does not help. I toy with denying the secondary charge of foul language but I know that nothing will deter my mother from laying into me with that brown leather strap in her wardrobe. As I grow older, my mother’s furious beatings with the strap that leaves long welts hurt less and less. I begin to enjoy the feeling of self-righteous defiance.

I also enjoy the look of fear on the faces of the girls Karen and I beat up. Occasionally her cousins Bernard and Tommy help us. We become a dough-nose kaffirtjie gang that intimidates everyone, even the kids in the older classes.

When I beat up a girl two grades ahead of me, I know I’ve arrived and the secret is out. Almost-white kids are wimps.