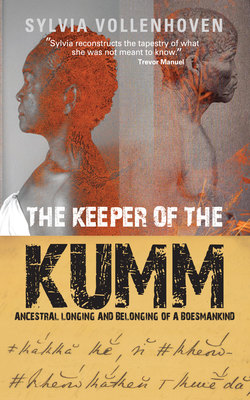

Читать книгу The Keeper of the Kumm - Sylvia Vollenhoven - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Loss and exorcism

ОглавлениеDefiant dust devils prance across the plains bringing a story the girl was not expecting that day.

We still wear apartheid race classifications like tattoos on hidden skin. South Africans have a way of doing rapid calculations based on subtle textures and tones, beyond the reach of outsiders. When the computing is done, we adjust our behaviour according to the all-important tag we have allocated the other person. Of all these tags that hint at identity, the one that has caused me the most harm is ‘coloured’. Decades of the new South Africa and colouredness is still a daily insurance of being marginalised. Reverberations of a heritage of genocide and dispossession.

I was not born with this tag. My birth certificate hints at a time when these things mattered less. It states simply ‘Mixed’. Behind the almost offhand classification lies a story of a hidden ancestry.

When I began delving feverishly into my connections with a Bushman visionary who lived in the 1800s, the trauma that surfaced was overwhelming. The pain of centuries, forcing me to embark on a journey. An exploration with //Kabbo became the key to unlocking the painful prison of colouredness.

But I didn’t expect in the beginning that an impassioned inquiry into who I really am would demand an exorcism.

I’ve burnt a forest of incense, chanted mantras from Betty’s Bay to Bangalore, and cleansed my space till the spirits left through sheer boredom.

And now here it is, a frightening reality that makes me wish I had never come down this road.

A line-up of the long dead stands waiting, souls jostling for space on white pages. I am afraid, but they will not go away. Stars on an inner sky. If I don’t tell the story of the gathering folk of this constellation, I will die.

Many months of weeping have given way to gut-wrenching howls. Waking up from a lifetime of fantasy is much like the passage through the birth canal. A painful, dark loneliness expressed in primal screams.

Sick and tired of a medical condition some doctors cannot name and others call ‘chronic fatigue syndrome’, I don’t have the courage to tell anyone what’s happening to me. To talk about the things that are vanishing, about losing pieces of myself. My voice seems to come down a long tunnel from a place I don’t know.

I wake up and do a body check to gauge whether I’ve lost anything important during the night. Each day another piece of my sanity slips away. I dress slowly. Everything is painful. My skin hurts, my body aches, my mind revels in fantasies of death.

I open a drawer and a favourite piece of jewellery is missing. There is only an empty box where my delicate gold bracelet adorned with tiny diamonds and emeralds used to be.

“Elize, have you seen my gold bracelet?”

“No, but you were wearing it when you went to Cape Town the other day.”

Things have started disappearing from my life. It started just recently. I anticipate draping my scarf with the shells that emanate soft sea sounds round my neck, but I can locate it only in photo albums. My reality has become a rickety tableau. Chunks are simply vanishing. I am homeless and jobless. I have wasted everything I owned chasing healers and cures. I know that when enough pieces disappear I too will vanish.

Too embarrassed to speak to others about these things, a slow acceptance creeps up on me. I live alone in a remote village and hardly ever get visitors. The gaps in the tableau are growing but I no longer care. If the spaces meet I will disappear. This I know. It’s a matter-of-fact, dispassionate knowing.

Sometimes when I run my hands over familiar places I feel the body parts of other people where mine should be. A former lover’s thigh or the hard pubic bone of an old man darkening the shiver of a young girl.

I want the high-pitched ringing in my head to stop. I want the ache in my body to understand the language of the painkillers. I want … I don’t want my life to close down while I’m still alive to experience every bit of the process.

When the illness gets worse, I am far away from home. I read books and watch films more avidly than I have for a long time. But missing elements prevent me from understanding, grasping information. I sit in a movie house looking at the end credits and wonder what happened in the film.

“Did you get that?” I ask a few times when I’m out with someone else. The explanations add to my confusion. So, I let the grey cloud settle and close my eyes.

I become devoted to my journal. I imagine that the daily writing is insurance against losing my mind.

The safety measure does not work. I wake every morning, struggling to breathe, as the panic emerges from the dark corner in which it resides at night.

Voices come and go, not attached to anything at all. Whispers of things I am losing, of things escaping that have been locked away in abandoned warehouses.

I dance alone in the light of early morning. The music softens the pain of loss, helps me lay out the pieces in some kind of order. Not so long ago I had a home, a family and a flourishing career. Everyone has left and the house is gone. I open the windows of the small, borrowed cottage where I live.

I take my dogs for a walk on the beach but I’m too weak and they sense it. They go wild, trying to attack everyone and everything around them. Battered by the effort to hold onto their leashes, I go back home. I no longer care much but I go to yet another healer, take medicines and surf the internet, hoping for a name, a handy description of some medical condition that I can claim.

Healer Niall Campbell sits cross-legged in front of me, dominating the small consulting room with his six-foot frame. For the first time in the many months that I’ve been seeing him, he is grave. Not a trace of a smile.

I tell him of stumbling through chaotic events clutching at only one source of comfort. An ancestral story I’ve started to write is like a beacon flickering across a dark, heaving ocean.

Stories know no boundaries of time and space. Stories know no limits of place. Stories travel from one realm to the next as easily as a stream falls to the ocean. It is given to a few to be the guardians of the story, to protect the treasures that touch the hearts of people. These guardians are the Keepers of the Kumm who roam the astral plains at will. My Ancestor //Kabbo is one such Keeper, a timeless visionary weaving story threads, delicate but powerful enough to hold the world in place.

I don’t understand when //Kabbo begins to talk with me. We, the hybrid people of a scarred city landscape, no longer know the language of the Elders. We shoulder the burden of the label ‘coloured’ with anger, frustration, embarrassment and occasionally a bit of offbeat pride. Once, when I was in my 20s, I was in hospital in a coma. When I woke up, a friend told me I spoke a strange gibberish full of clicks while I was unconscious. We are Africans shaping new identities with deep longings where the old ones should be. Niall, a highly trained diviner, teaches me that words are relatively futile in this process, especially English words. Listening to the call of the Ancestors is not a verbal experience.

“So with two disabled languages, English and Afrikaans, and an upbringing stripped of guidance, I have to write a story about a Bushman visionary who lived in the 19th century?” I ask nobody in particular.

The answer from Niall and the spirits who have burst into my world, one dominated by the deadlines of journalism, is a resounding “Yes!”

To describe Niall as a sangoma or traditional healer is accurate but insufficient. The word sangoma has lost some of its currency, its real meaning diluted, limited by its transposition into English.

I have been brought up to abhor these saviours of African sanity. Niall, the Botswana-born son of a Rhodesian4 policeman, is a qualified diviner, a doctor of traditional ceremonies as well as institutions and my spiritual teacher. In Botswana he is called a Ngaka ya diKoma, a Doctor of The Law.

The irony of a white man guiding me through the complex maze of African tradition, a man who knows the law before laws, embarrasses me. I don’t really know why, it just does. Niall has been helping me step by step through the process of responding to the call from my Ancestors.

The Ancestors arrive unobtrusively and once they enter the old rules do not apply any longer. They come to teach us of the battle that ensues when worlds collide and of the places where healing can be found when the chaos subsides. Sometimes our immediate Ancestors work with visitor spirits but the process is tricky and the pitfalls are many. In the beginning I don’t know any of this and see only chaos. Feel only pain and confusion.

//Kabbo /Han#i#i /Uhi-ddoro Jantje Tooren, a visitor spirit and Story Guardian, a Keeper of the Kumm, arrived in my life many years ago, but sits patiently waiting until I am ready. Since this 19th-century visionary entered my world, the fine line I walk between reason and chaos has become a razor wire some days.

I have no money and I’ve borrowed from the bank and from friends. My total debts are now larger than a decent annual income. It frightens me to write this. The needle indicating my energy levels barely inches out of the red zone.

I haven’t seen Niall for months as I battle to find enough money to pay my rent and bills, paying one friend back only to borrow even more from another. I tell him about an illness I’ve had since I had to shoot a short film in a room where post-mortems are done, at a pathology lab in Hermanus.

“Next time you have to work around dead people, come to me first,” says Niall as I sit shivering opposite him in the midwinter cold.

“I’ve been getting ill every few weeks. I spend half a month in bed and the other half working myself to a standstill to make up for it. But no matter what I do, I feel as if my life is closing down. As if I am operating in narrow fissures, in minute breathing spaces, that remain open with great difficulty.”

I wake up tired. My head throbs, especially when I lie down. A field of crickets is furiously busy in my ears. I am afraid to eat because so many things make me nauseated. In the middle of the night, I sometimes have to go to the bathroom to throw up. My body aches and even short spells of writing make the pain in my left shoulder unbearable. My stomach is in a permanent knot, no matter how many laxatives I swallow. Any relief I gain through exercise is limited because my left knee is painful and swollen. My skin is patched with eczema. It feels as if my system is fighting itself. Specialists cannot find the cause of the constant pain in my left side.

“I know I need healing but I don’t know how. I am so, so tired,” I tell Niall.

I don’t say that I’m hardly making any progress with my writing, that I skim over the growing pile of debt that keeps me awake at night, and I don’t mention the fear that has grown too big to name.

“I have a suspicion about what might be happening to you but I will have to check to make sure,” says Niall.

For the first time, there is a shadow on his face. He is usually all light and smiles. No matter my dilemma, he shows me how much I have going for me and sends me away with healing herbs to wear and to put in my bath.

This time is different.

I knew it would be different because I couldn’t sleep and felt so sick that I almost cancelled my appointment. And when I got to his gate, he came out to greet me looking puzzled.

“Did we schedule you for today? I have someone else coming right now.”

This slight upset is enough to make my throat ache, as the tears are about to flow.

“Not again. This confusion is happening all the time,” I say softly.

We stand at his gate in the half-hearted sunshine of the winter morning and I show him the text message I sent to confirm our appointment at 10am. He in turn shows me the trail on his phone and my reply is simply not there.

“I didn’t get your confirmation so I assumed you couldn’t make it,” says Niall.

He sees the panic in my eyes and tells me to come back in an hour.

Lately, this has been happening a lot. Two mobile phones, a fixed line, a desktop computer and a tablet … But some days everything freezes up. Nothing goes in and nothing comes out. It’s as if there is a steel wall around me, pushing me into oblivion. I am being cut off from people, from opportunities.

Several projects have attracted great interest from all the right people initially, but then suddenly the enthusiasm disappears. My emails and phone calls are unanswered. Sudden dead ends. I am not accustomed to this. At one point I throw a pile of books and notes into a corner of my office and give up. No matter how hard I work, I can’t make any headway. For almost six months, I haven’t been able to get past a chapter about death in the book I am writing.

“You’ve won. I don’t have the energy to fight this any longer. I give up,” I say.

A voice, soft but urgent, intervenes: “Don’t converse with it, whatever you do!”

I wait in a coffee shop for an hour and return to Niall’s house on the lower reaches of the Steenberg, a mountain that abuts the Cape Town suburb of Tokai. We make small talk first, as we always do. I remind him of the dream I had before I met him. Recently, I looked at the entry in my journal. It is accompanied by a sketch. My drawings are terrible, so usually I don’t even try.

“It’s a description of the house you used to live in,” I say.

Niall’s old house was number three. In my dream, before I had heard of him, I saw it as the third house from the corner.

“You went into another room while I struggled with a huge darkness. ‘Like a limpet on my back’, my journal says.”

I’ve told him about this dream before. I don’t know why I’m repeating it. He listens attentively. I also tell him about dreams of dying and a bit more about the shoot at the pathology lab. He interrupts in his usual gentle style:

“When did you do the shoot?”

“Several months ago now,” I reply, and tell him how I had to go home to sleep halfway through the shoot, except that it was more like losing consciousness than sleeping.

Niall’s gentle insistence stops me again. Something about the way he is looking at me makes me lose track of my story.

“When was it, exactly?”

“About six months ago, December last year I think.”

My story fizzles as Niall’s face becomes very serious. I’ve never seen such a shadow between us before. He reaches for the genet-skin pouch in which he keeps his traditional ‘bones’. The objects in the bag are a talismanic mixture that also includes a few bones. Only once before has he used this method of divination – to reassure me that in spite of my concerns about working with an ancestral spirit all would be well.

“Give it a blow if you will,” he says, opening the pouch and pushing the contents toward me. We sit opposite each other on the floor. The room is bedecked with the comforting symbols of African healing and divination. Neatly stacked jars of herbs flank a small altar. The wall behind it is covered with brightly coloured cloth. A tangible border between us and the horsey suburb in which he lives.

I breathe deeply and blow into the pouch. When Niall holds the bag close to him and chants an incantation, I close my eyes in silent prayer. The chanting summons his guides. Their presence is tangible. It is the feeling you get when a group of powerful personalities has walked into a room.

I continue breathing deeply and praying. After several minutes of incantation, Niall opens his eyes and empties the contents of the pouch onto the reed mat between us. He doesn’t touch anything but uses a whisk made of bone and animal hair to point at ‘constellations’.

“Yes, it’s just as I thought,” he says looking up at me. Nothing in our relationship has prepared me for seeing the expression of dread in my sangoma’s eyes.

What he says next doesn’t make sense to me as a complete sentence, not at that moment and not for a long while after.

“You have picked up a death energy … the energy of a dead person, maybe even several entities, and that is what is causing the chaos in your life.”

“No, that can’t be. I feel a bit ill and things have been difficult, but …”

In denial, I tumble mentally from one response to the next without absorbing what Niall is saying.

“I don’t look like someone who is cursed. Shouldn’t my hair be falling out or my house be creaking with sulphurous ectoplasm like in the movies?” I think.

I miss some of Niall’s words and run away deliberately from others:

“Terrible … hate doing this … very dangerous … must do something fast.”

Niall sees my panic and confusion so he repeats a few things slowly. Even then the words drift between us like unclaimed baggage in an airport terminal. Until one comes that I have to deal with because it knocks me over.

“Do you know the Femba ritual?”

I look at him blankly.

“Exorcism!”

That single word makes all the others disappear. A host of frightening stories come rushing in to stand alongside the word Niall has just uttered.

But then something even more frightening than the E word comes at me. It is the repeated, seemingly benign, use of the second person singular pronoun. Why doesn’t he say ‘we’?

“You will have to find a sangoma who can do Femba for you. It is not done by one person. It has to be done by a team of sangomas. You will have to do this as soon as possible.”

“How do I …?”

And then more silence.

I assume that he wants nothing to do with the dark force that is sucking the life out of me. I feel more alone and frightened than I have ever felt in my entire life.

As he notices the tears begin to fall, Niall says, “I am not allowed to offer.”

Perceiving my fear, he adds, “In terms of custom and tradition, I can’t offer to do it but I can tell you that I am qualified to perform the ritual. You can seek a second opinion and you can choose anyone you want. I charge five for the ritual and two for the follow-up.”

At last my mind has something to fasten onto in the wake of the fear and confusion brought on by the E word. “Five what?” I say, exposing my complete ignorance of the terrain Niall is treading.

“Five thousand for the Femba ritual and two thousand for the process that has to happen after.”

I stop crying.

“He will do it,” I think, and I feel almost elated.

Then the sadness returns as I realise that if I give a group of sangomas R7 000 I will not have a place to stay. But I don’t say that in case he goes back to talking about ‘you’ and not ‘us’ again.

“I will raise the money,” I say, with little confidence.

“Let me know when you want to do it. I have to gather a group of sangomas. It’s not something I like doing. It’s very dangerous,” says Niall. He hasn’t smiled once since looking at the bones.

Before I go he explains: “You have been working with your Ancestors. This opens up portals and these energies have used the openings to get to you.”

I walk away, playing the conversation over and over. For the first time since I have been consulting Niall, he takes me all the way to my car. When I get in and he walks away, I feel like a child who has been abandoned in a dark, evil forest.

Niall decides on a date for the Femba exorcism and with each new day my fears intensify and grow untameable.

For as long as I can remember, my dreams have come to my rescue. But other than during a brief spell of New Age seeking, I’ve never thought it necessary to seek help to interpret dreams.

“You have to learn the difference between a dream and a vision,” my grandmother, Sophia Petersen, would say before imparting the details of her encounters with the Divine.

One night when the prospect of the ritual had been following me like a haze of midges, I dream of flying higher and higher while Ryan Lee, my son, stands below, watching. I am wearing a bright jumpsuit and when I fling my arms wide, the sun’s rays catch its many colours.

In front of me, there is a multi-storey building, so I descend a bit to see inside. I enter a high-ceilinged room on one of the upper floors through a window. I see Sri Sri Ravi Shankar, a guru I met at an Indian ashram, wearing reddish-orange robes. He almost falls over in fright as I circle the room, close to the ceiling.

Slowly I float down to sit and talk to Guruji, which is the name his devotees use.

“I started flying bit by bit. At first I used swimming strokes and could not go very high but now it is easy. The first time I wanted to ascend was in the ashram,” I tell him.

Ryan has followed me here and I explain to him that the ashram is in Bangalore. The guru is a bit put out and much more ordinary than I remember.

We discuss diet and he says, “You have to eat lighter to become lighter.”

A couple of days later, on the eve of the Femba ritual, I have an intense headache when I lie down. My temperature goes haywire. I veer between shivering and sweating. Several times I fall asleep exhausted and then wake up with a start. My stomach cramps and rumbles throughout the night, as if something is boiling in my insides. In the early hours of the morning I read The Hundred-Year-Old Man Who Climbed Out of the Window and Disappeared. But the words of the humorous Jonas Jonasson novel somehow get lost between the page and my mind.

I can’t bring myself to switch off the reading lamp. Only when the winter sun nudges the curtains does the fear subside a bit.

“I will explain what is going to happen,” says Niall when I arrive at his place the following afternoon.

I have been to his cottage many times but the rooms seem unfamiliar today. I feel as if I am visiting for the first time.

“I have done a ritual cleansing,” Niall tells me.

One by one his fellow sangomas arrive to join Niall and his brother Colin, who practices traditional healing in London and other parts of the world. He just happens to be in Cape Town for a visit. The healers each wrap African cotton cloths over their Western clothes.

“How are you feeling?” someone asks.

I smile but only slightly in case my facial muscles let me down in my feeble attempt at looking relaxed.

In Niall’s usual consulting room, a cave-like place that is lower than everywhere else in his cottage, we face each other cross-legged once more. He is explaining the process but I hardly absorb any of it.

“Please put this on and face this way,” Niall says.

At last, simple instructions I can follow. I drape the traditional cloth around my shoulders. Niall sprinkles snuff and alcohol from a small vodka bottle on the ground. Then we kneel, facing East, in front of the altar where he talks with his ancestral spirits. Today the Setswana chants are especially soothing to my ears. I don’t understand the words but the sound is comforting.

We go back into the big room where someone has lit a fire in the small grate in the meantime. It is the time of the winter solstice. As the sun drops behind the Steenberg, the cold in the valley is biting. I look out through the window at the horses. This mink & manure neighbourhood is a most unusual setting for an ancient African exorcism ritual. A polite, Sunday-religion neighbourhood where people worship share certificates. In Retreat, a few kilometres from here, I spent most of my childhood without knowing that this suburb existed.

“You have to sit in the middle here,” says one of the sangomas, a young woman.

Furniture is moved out of the way and the woman rolls out a traditional grass mat, decorated with a huge animal motif, for me to sit on. I feel as if I am about to be sacrificed. As I wait, I make small talk with Colin.

When I was working in Ghana recently, I reached an all-time spiritual low – the rather clichéd dark night of the soul. While trawling the internet in the hope of finding a clue to the cause of the feeling, I found an interview with Colin about his work. I listened to the podcast repeatedly and afterwards wished I could meet him to find out more about the brothers Campbell, the white sangomas from Botswana.

Two years down the line, I am waiting for them to perform an exorcism ritual. It feels as if I am very much in the passenger seat of the vehicle of my life.

Horses neigh outside the window as they are led from the paddocks to the stables. My mind travels to the people of the main house and their rich white family small talk in front of the TV.

“I have to ask you to get undressed and come back and sit here,” says Niall, pointing to the lion’s head on the reed mat.

I pick up my purple basket, the one I got for Christmas from my friend Bea, and head for the bathroom. She was the first to tell me I was channelling an ancestral spirit. At the bottom of the basket, hidden very deliberately from sight, is the small white Bible my mother gave me on my 18th birthday. Hedging my bets.

“Here, let me help you,” says one of the sangomas who has to cover my leotard and T-shirt with traditional sarongs. I am a bit embarrassed at the possibility that she might see the Bible under my clothes in the basket.

I sit in the middle of a six-person circle of sangomas. One healer is beating the sacred cowhide drum, said to have a spirit of its own. Two of the women are helping Niall prepare medicine in a wooden bowl. He is trembling slightly.

Myself and Ryan Lee, who is helping to film the event, are the only black people in the room. I think about the ancient dramas being played out here – the descendants of colonials nudging me closer to my African heritage. Harking back to a time when the term ‘coloured’ did not exist.

It’s been a very long journey from my upbringing in a fundamentalist Seventh-day Adventist family to an exorcism and cleansing with a team of white sangomas. The forbidding dictates of the Old Testament have dominated my life and within that milieu African spirituality was not even up for discussion.

But no amount of dogma and packaged prayers have kept my Ancestors at bay. It is time to be ripped apart, and to lose everything, especially my religion. Lose even the comfort of people I love.

The stars of my inner sky light my way as I descend into the chaos. The line-up of the long dead who have been following me around move closer. My story is their story. It is time to remove the boundaries that have forced us apart. Time to go back to the beginning … or even further.

Time to explore where the damage of colouredness really began.