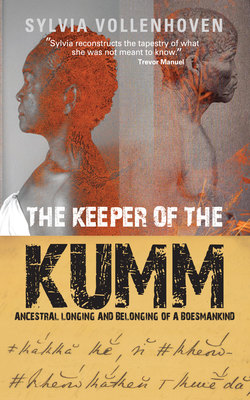

Читать книгу The Keeper of the Kumm - Sylvia Vollenhoven - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Prologue

ОглавлениеThe Keeper of the Kumm1

Exorcising apartheid

The illness started unobtrusively but within a few years I was partially bedridden. For the first time in my life I had to live with unending pain and fear. And some days, the lack of a name for this illness made me wish I could die.

I told my story over and over to slick city specialists. But after exhausting conventional cures, I had to swallow my cynicism and consider options that forced me to delve into African traditions. It is the hardest thing I have ever done. Years later when the fog of illness finally dissipated, I began to see my world clearly for the very first time since I was a child.

It has been a long and difficult journey.

In the ’70s, when I landed my first job on a newspaper, I applied for my passport immediately. Carried it to work every day in case of rapid deployment to some far-off place. Only a brief holiday in Swaziland saved the shiny green document from obsolescence in those early years. But as my career progressed, the jet-setting that I had fantasised about in my 20s became a reality.

Decades later, when I was grappling with a debilitating and mysterious illness, a powerful reality dawned. I have travelled widely, written so much about so many things, covered the unfolding story of South Africa extensively, but I know absolutely nothing about myself. Who am I? Where do I come from? What is my place in the landscape of Africa’s history? My family tree is blank save for a few generations. I don’t even know who my great-grandparents were.

So a few years ago, as I lay in bed hoping that complete rest would get my strength back, I began to delve into the story of //Kabbo, a 19th-century Bushman visionary. It is my belief that my ancestral journey with //Kabbo became the key to unlocking the prison of an illness that I still cannot name. The ancients say this kind of sickness is the Ancestors’ way of getting our attention. My grandmother, if she had been alive, would have said it was a calling. And indeed, with reading about //Kabbo, something magical began to happen in my life.

Almost two centuries ago, a Bushman boy (San is a term some prefer) called /Han#i# (Father’s Desire) was born in a small settlement near Kenhardt in the Northern Cape. It was 1815, the year that Napoleon was defeated at Waterloo and Britain became the 19th-century superpower. Wrested once more from the Dutch, the Cape became a British Colony, and hordes of marauding settlers pushed into South Africa’s hinterland.

/Han#i#, an especially gifted child, grew up at a time when settlers and other Africans were intent on the complete destruction of his people; they were driven off their land, their languages were banned and they were enslaved. Boer commandos formed ‘hunting parties’ with the aim of slaughtering an entire people. When /Han#i# was about nine years old, a great famine killed his father and two older brothers. After the initiation rites of his first hunt, his adult name became //Kabbo, the Dreamer or Visionary.

When //Kabbo was in his early 30s, the colonial governor extended the boundaries of the Cape Colony, taking away almost all his people’s land, and thereby providing a conducive environment for Boer commandos to hunt them down.

//Kabbo had a vision that he could save his people. And so in 1870, //Kabbo /Uhi-ddoro Jantje Tooren, a pipe-smoking, revolutionary Bushman hunter driven by his need to safeguard his fragile culture, travelled hundreds of miles to find city people as he had heard that they could write down stories and preserve them in books.

The result of this vision quest is an archive recorded over a thousand days and nights. More than a century later, it was entered into UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register. The Bleek/Lloyd Archive, housed at the University of Cape Town, contains over 100 notebooks and more than 12 000 handwritten pages2. It is the work of Victorian philologist Wilhelm Bleek, his sister-in-law Lucy Lloyd, and their teacher informants3. //Kabbo was the main teacher. But we the descendants of //Kabbo and his people are largely unaware of the existence or significance of the archive.

And in the same way that //Kabbo journeyed hundreds of miles to find Bleek and Lloyd, he reached out across time and space to the seaside cottage where I lay unable to work or do much except read, reflect and write.

As much as we feel that we choose the stories we wish to tell, we have to accept that some stories choose us. I’ve always known I wanted to be a storyteller. Never imagined anything else. Journalism became an outlet.

I grew up in the ’50s and ’60s when apartheid faced only a weak and battered opposition. I lived in Soweto while I did my journalism training, during the height of the youth uprising of 1976. The following decade I became a correspondent for a foreign media group and covered the devastating effect of apartheid. Standing outside the prison gates, watching Nelson Mandela take his first strides towards freedom felt like a dream. Afterwards, covering the negotiations that preceded the new South Africa, the dawn of democracy and our first elections took me ever deeper into a painful collective history.

With apartheid out of the way I could focus on other aspects of what ailed us as a nation. My own pain came rushing to the surface like lava from an erupting volcano. As I delved into the story of a long dead Ancestor, I began to understand that centuries of trauma have to be acknowledged before we can move on. Until we see ourselves in //Kabbo and engage with the //Kabbos in our own histories, we will continue to flounder in a sea of social problems.

To tell a story of this depth and magnitude, I have had to drop my conventional notions of time and space. Balance my respect for the scientific by honouring tradition. Create a place where African mysticism and modern knowledge sit side by side with ease. And finally, I have had to unearth my own story before I could access the meaning of a 19th-century visionary, rainmaker and shaman bursting into my life.

And now that I can see myself and my world clearly, I’ve found that a powerful movement has begun to stir. What started as a flicker of recognition in conversations and encounters has become a groundswell of social change. A recognisable crusade. It has been called into being to acknowledge the pain as well as the heroism of our Ancestors, and goes beyond the achievements that reside in the selective memory of popular political movements.

There are Khoekhoe language lessons at The Castle of Good Hope built by Jan van Riebeeck, there is an annual traditional Rieldans (a traditional southern African dance form) contest held at the Afrikaanse Taalmonument erected by the apartheid state and there is a movement of Khoisan activists reclaiming our rightful place.

The Keeper of the Kumm is my intuitive and creative response to a social current that is moving us away from the dangerous shores of division. Away from the systematic dispossession of being coloured to being an African with a claim to the land and its story.

Globally there is an awakening to a new way of thinking, a new way of seeing ourselves in the landscape of the past. With this awareness, neat timelines give way to a non-linear, interrelated reality.

My own awakening has helped me see my illness, which defied mainstream medicine, very differently. But it’s been extremely hard to cope with a reality that runs counter to my no-nonsense journalism training. To accept that a physical sickness in the 21st century can be connected to events that happened hundreds of years ago. So I gave up using my intellect to try to make sense of it all and accepted the magical journey that led to healing. A journey that rescued me from a prison that I did not know existed, even though I was trapped inside.

There is only one reason I am telling this story of loss and redemption. I simply have no other option.