Читать книгу Raised in Ruins - Tara Neilson - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER THREE

| “4th grade correspondence our 4 children school | Outside, beyond the lapping of the water |

| housing our 4 desks with the attached chairs | Against the worm-eaten logs of the wanigan |

| and open up tops and rusted 50 gallon gas barrel stove. | I hear my father’s chainsaw We will haul wood for recess.” |

| —my Fourth Grade poetry composition |

THE LINDY LOU was hauled out of the water and held upright by a wooden cradle Dad built for it near where he eventually moved our floathouse, so high on the beach that our home only floated during the highest tides of the year.

After Dad did some repairs to it, Muriel and Maurice moved into the sole remaining, still-standing cannery building on the property, the little red cabin we’d noticed on our first visit as it stood on the edge of the creek across from the ruins.

The Forest Service had marked a trail between the two sides of the cannery. Dad civilized it by cutting down some small trees and laying them down over boggy spots, and overall made the trail easier for the Hoffs to follow. Muriel took it every morning to teach us in the wanigan.

The wanigan was tiny. It was one room with a small loft. It had a front and back door that slid in wooden troughs, like a boat door. There was a hand-hewn counter at the back with a sink that had no running water, and a four-paned window above it. In one corner the wood stove, made from an old fuel drum, squatted.

The interior and exterior were all raw wood, unpainted, with visible nails and hammer dents in floor, walls, and rafters. But this was common to Southeast Alaska where the timber-loving men in the area disliked splashing paint around and strongly resisted all attempts to put anything but varnish on floors or walls.

The small building had served as a home for my grandparents while they built a house on land, and from the first my brothers and sister and I loved playing in and on it. Mom handwrote on lined yellow paper a story called “The Wanigan Kids” and each of us, plus our cousin Shawn who came up in the summers to visit his dad (Rand), had a starring role in the story.

It was a Wizard of Oz story, but instead of our house being whirled away by a tornado, in Mom’s version the wanigan broke its mooring lines during a high storm tide when just the six of us kids were aboard, and we floated away from adult authority. Instead of the fantastical sights and experiences of Oz, Mom asked each of us to contribute an idea to the story and we decided on adventures of coping with the real and present dangers of the Alaskan wilderness.

She read many books to us and we loved all of them—but we loved none more than “The Wanigan Kids,” which we clamored for her to read all the time.

The small, weathered wood floor of the wanigan was scuffed by our four desks. (Chris was too young to attend school yet.) With only three small, four-paned windows to let the light in, we had to have a kerosene lantern burning to be able to read and write, especially in the morning and in the afternoon during the long dark winter months.

On wash nights the desks were pushed to the back to make way for a large tin washtub, oval in design. With water heated on the stove, clothes and bodies were washed. The clothes, washed first, were hung on lines strung below the roof. In the cozy yellow light of the lantern, the windows turned opaque with steam as we scrubbed and splashed below the dangling legs and arms of the clothes, each of us getting a turn. The clothes would continue to hang over our heads when we did our schoolwork.

Dad built a long floating walkway to shore so we could get off to play at recess or go home for lunch. When school first began with Muriel as our teacher, we were given tests by the regional school district that would oversee our education by mail and floatplane visits. The tests were to see where we were at, academically. In between each segment of the testing we were allowed to run around outside for a few minutes to let off steam. The tide was high so we ran across the floating walkway, listening to the water splash under our assault.

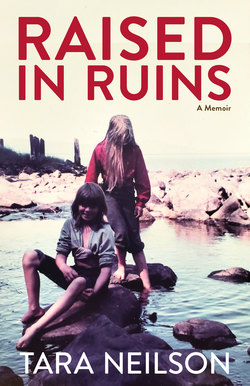

Megan’s watercolor painting of the wanigan, for which she won first prize in a statewide art competition.

We’d been warned never to go far into the woods, and under no circumstances were we to use the trail that connected the two sides of the cannery. There was bear sign everywhere and my parents said that we shouldn’t go on the trail without an adult who’d carry a gun.

At this point, Muriel announced that she didn’t believe in guns. “They’re anti-intellectual,” she said. “And they’re counterproductive. The reason that people get mauled by bears is because they take aggressive weapons into bear territory. Bears are intuitive. This is their world, their land, and the onus is on us to live by their rules and be respectful of their rights and feelings.”

“You’re saying we shouldn’t carry guns?” Mom, as much as she disliked guns, couldn’t find it in her heart to embrace the idea. Not with five kids to protect.

“There’s enough evidence out there that bears can sense the hostility of negative and aggressive thinking by humans. They’re tuned into our individual auras. Maurice and I won’t carry a gun into the woods. I advise you not to either.”

Even I, nine years old at the time, thought this was an argument that bears would not feel compelled to honor. Dad, as usual, kept his thoughts to himself, while Mom tried to argue with Muriel despite how much she would have liked Muriel’s argument to be true.

So my parents, to preempt anything she might teach us on the topic, told us kids that we could only go on the trail when Dad was there with a gun.

This, under Jamie’s leadership, meant that as soon as we were let out of school on those short breaks between tests, we had to see how far we could get on the trail running as fast as we could, before we had to turn back in time to do the next test.

The memory of racing along the dry edges of the squishy, muddy trail (so that, as Jamie pointed out, we would leave no tell-tale marks on the trail or on our boots) marked by pink and yellow surveyor’s tape, the trees looming above us, the threat of bears around every corner, is vivid in my mind. We giggled breathlessly, exultant at being free of adult supervision, at having outsmarted the adults, at surviving the daring escapade.

Megan and I gripped Robin’s hands and raced him along behind Jamie. I was terrified of all the bear stories I’d heard, I had nightmares about them breaking into our house while we slept, but there was a laugh-in-the-face-of-danger joy about those urgent races deep into the verboten wilderness that lingers with me to this day.

• • •

When Mom first met Muriel in Meyers Chuck, she’d admired Muriel, in the way Mom always admired women she saw as more capable and take-charge than she was. Muriel was a registered nurse and saw herself, she said, as an Earth Mother type who wanted to live wholly off the land.

This sounded like the perfect person to accompany us into the wilderness, to shore up Mom’s less practical nature and provide immediate medical help should it be required. Maurice was not at all practical and had no wilderness skills, but he was friendly, genial, and intellectual. He tended to smile and nod, backing up whatever his wife decided. Where he shone was in singing folk songs and accompanying himself on guitar, like any back-to-the-lander worthy of his salt.

Muriel had traveled widely and had many hair-raising adventures to share. She found herself, she said, invariably in the position of having to stand up to abuses of power and ethical wrongdoing. “You must always stand up for what you believe in; you must be true to your convictions.”

Mom loved this because her instinct was to always stand on principle, no matter what it cost.

Everyone was pleased, thinking the two couples would be a perfect match at the isolated cannery site. But before we left Meyers Chuck, something happened.

A friend of both Mom’s and Muriel’s was the subject of controversy. When the village women got together to hash out what should be done and the conclusion was that the mutual friend should be driven out of the community, Mom stood up and said they didn’t have the right to make that choice; they were all the woman’s friends and they should act like it.

Her principled arguments, as always, were made as an emotional appeal and dismissed by the majority.

Muriel was silent on the subject. Mom asked her about it later—Muriel was at least as close to the woman as Mom was. Plus, other women would have listened to Muriel, who was so certain. Why hadn’t she stood up for her friend? “After all, you’re supposed to stand up for what you believe in,” Mom reminded her.

Muriel said it wasn’t any of her business and she preferred to keep out of it.

Right then Mom started to have doubts about heading into the wilderness with Muriel and Maurice, not to mention having Muriel teach her kids, but everyone was already committed.

• • •

For physical education (PE) we hauled firewood. Dad split it and we stacked it in rows on the wanigan’s front porch.

As it grew colder Dad had his hands full finding, sawing, and then splitting enough firewood for the floathouse, the wanigan, and the Hoffs’ cabin. Despite their back-to-the-land, sweat-andcallus aspirations, neither Muriel nor Maurice were interested in harvesting their own firewood.

They said that in exchange for his children receiving an education, Dad should provide them with firewood. So Dad would come home from a full week of hard physical labor as a scaler and bucker at the logging camp, and he’d spend the weekend splitting firewood like a machine. The only sign to us kids that he was human was the sweat pouring down his face and the steam rising from his head in the cold air.

Dad filled Maurice’s skiff full of firewood—several cords’ worth—and towed it over to Muriel and Maurice’s cabin. Dad figured it would last them a couple months at least, since the cabin was tiny and it wouldn’t take much to heat it.

The next day, the last day of Dad’s weekend before he had to go back to work, Maurice knocked on our floathouse door.

“We need firewood.”

Dad stared at him. “I just split several cords for you.”

“Unfortunately it had other plans and floated away.”

“How could it float away? Didn’t you tie the skiff to a tree above the tideline?”

Maurice offered an amused, worldly shrug. Obviously the loss of the firewood was an Act of God. What can you do?

Dad was fit to be tied. But, as Maurice indicated in his indirect, urbane way, they needed firewood, and since the agreement was that Dad would provide it in exchange for Muriel teaching his kids, it was up to Dad to supply it. And resupply it.

• • •

I recently asked Robin what he remembers about Muriel and Maurice. Though he’s four years younger than I am, he’s often my go-to source for memories because he has the kind of mind that keeps arcane details on tap.

He responded: “I hated her so much that I have no memory of her or him. I erased her from my mind.”

I understand perfectly why he feels this way.

Muriel wasn’t an easy person to like. She had a curious habit of talking to adults like they were children, and to children like they were adults. She went around braless to indicate her free-spirited feminism that unyoked her from the backward Establishment—while all the time trying to form her own Establishment that everyone else was required to support.

What none of us realized, when Mom and Dad accepted Muriel and Maurice as equal members of the plan to colonize the cannery, was that this agreement would set us on a collision course that would lead to an epic clash of wills. Not between Muriel and either of my parents. No, it was between Muriel and one of her students.

When Robin came along, the fourth child in the family, he was so cute and had so much personality that everyone adored him. He was precocious in a funny way, with an ironical take on life that was ridiculous in one so young. As a toddler he walked around with his bottle hanging out of his mouth and talked around it, like a 1920s gangster talking around his cigar. At the same time he had an infectious personality with enthusiasms that swept everyone along. Up to that point, the only fly in his ointment was when Christopher came along a year after him and knocked him out of the prestigious baby slot.

Chris, one of the happiest, most harmonious babies in history, adopted all of Robin’s mannerisms including Robin’s inability to pronounce his Ls. Chris’s failing in this area spurred Robin to take him in hand and demonstrate a correct pronunciation.

When Chris said something about Muriel and Maurice’s boat, the Lindy Lou, Robin would immediately deride, “It’s Rindy Rou—not Rindy Rou!”

Needless to say, Chris’s speech didn’t improve.

Muriel zeroed in on this fault immediately. All of her bully pulpit instincts became laser focused on fixing the problem that was Robin’s speech. The rest of us kids, self-starters who could teach ourselves for the most part, held little interest for her.

“You’re not doing it right. Touch your tongue to the roof of your mouth, press your tongue to the back of your top teeth, and make an L sound.” She demonstrated.

I did it myself, surprised to discover a skill I’d taken for granted up until then.

Robin stared at her in the wintry light creeping in through the windows. The little cabin smelled of crayons and finger paint, kerosene from the lamps, cedar firewood, and the seaweed that it rested on when the tide was out and it was no longer floating.

“Do it like this,” Muriel ordered, and demonstrated again.

He made a sound through his teeth.

“No, not through your teeth. Open your mouth and do it. No, that’s not it either. Try it again. Are you watching me? Do you see how I’m doing it? Tara, show him how to do it.”

I looked at Robin’s downcast face and uncomfortably demonstrated.

“There, that’s how you make an L sound. Do you see how easy it is? We’re all doing it. Come on, everyone, show Robin how to make an L sound.”

Muriel, Jamie, Megan, and I made L sounds while Robin stared down at his desk. I’d never imagined how taunting and belittling a prolonged L sound could be, when an entire group of people did it toward the youngest person in the group.

“Now you do it, Robin.”

Robin remained silent.

“Did you hear me, Robin? You’re not deaf, I know you can hear me. Now you’re just being obstructive. Do you want to grow up with a speech impediment? Do you want to be the butt of jokes, to look like a backward person? Do you know how that will affect your life? I know, we all know, don’t we, kids?”

I looked at Robin, and tried to explain to Muriel. “He knows the R sound he’s using instead of an L is wrong, he tries to tell Mitmer how to say it right—”

“His name is Christopher, not Mitmer. And that’s another thing. If you don’t learn your Rs,” she told Robin, “you’ll be responsible for your younger brother’s speech problems throughout his life. Do you want to be responsible for that? Do you want to make him the butt of jokes, mocked and laughed at by people wherever he goes? It will be all your fault. Do you want to live with that?”

Robin scowled and his lower lip crept downward, revealing small kindergarten teeth clenched together.

“He tries at home, my mom works with both of them on it,” I tried again.

Her pale eyes fixed on me. “Obviously that isn’t working, is it, Tara? You’re not helping by making excuses for him, and neither is your mother. Robin, neither you nor I am going to leave here today without you learning how to pronounce at least one L correctly. That isn’t too much to ask, is it kids?”

Robin never again tried to make an L sound in school. In fact, from that point on he refused to cooperate with her in any way. And she refused to admit that she’d lost his cooperation, continuing to harangue and goad him every single day.

It’s probably a minor miracle that Robin learned to speak his Ls without a problem. Her Ahab-like quest to stab at his speech impediment to her last breath made it hard for the rest of us to concentrate on our own work, which she paid little attention to anyway. All her focus was dedicated to getting Robin to give in and submit to her authority.

Robin, five years old doing battle with a college-educated woman in her thirties, never gave in. Instead, he discovered that he could hold his own against even the most self-certain adult. There was no going back after that. His cooperation in anything was almost impossible to win from then on.

In addition to this clash that impacted everything, tensions continued to rise over Muriel’s and Maurice’s expectations that Dad labor for them and keep them supplied in firewood. Due to their inexperience with a wood stove, they treated the wood he cut wastefully. They overheated their small cabin due to their ignorance of the stove’s damper and draft and had to have the front door open to cool the place, burning through the wood Dad provided far faster than he’d calculated. When they ran out they became annoyed that he didn’t fulfill his side of the bargain instantly, leaving them with a cold cabin to live in.

Muriel was someone who needed the admiration of others and felt the bite all the more keenly when it was withdrawn, which was what happened with my parents—with Mom in particular, who had been so impressed by Muriel when they first met.

By the time Maurice was offered a job in a town to the north of us a few months after the move to the cannery, relations were awkward and strained enough for everyone to be okay with them moving back aboard the Lindy Lou and saying their goodbyes. That was the end of their back-to-the-land aspirations. They never again lived so remotely.

We were on our own.