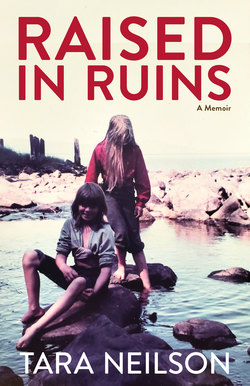

Читать книгу Raised in Ruins - Tara Neilson - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER FOUR

“Gee, I thought watches floated.”

—Chris, experimenting with our only timepiece, Dad’s not-waterproof watch, in a pan of water

ONE NIGHT, when the wood box that Dad had built next to the front door was empty… I climbed into it.

I could hear my family inside the house talking, laughing, and arguing. Robin’s and Chris’s voices that couldn’t pronounce Ls piped higher than everyone else’s. Their voices were muffled so I couldn’t hear exactly what they were saying. They were the only human voices for miles.

It was a moonless night, with degrees of black that only the wilderness knows. Up along the wall of the house was the big bay window with a puckered bullet hole in it, not unlike the bullet scar in Dad’s back that he got in Vietnam.

Golden kerosene lamplight spilled out, lighting the railing and gravel beach. The forest stream flowing beneath the logs of our house gurgled unseen, winding down through musky seaweed to the bay. The cannery superintendent’s house had once stood not far from where our floathouse was. Oil and kerosene lamplight would have spilled out of its twelve-paned windows on the same little bay, surrounded by the same pointed silhouettes of trees that were a deeper, more impenetrable black than the sky.

I stared up at the stars and thought about time. The light from those stars, Jamie had said after reading one of the science books he was always asking Mom to buy him, was millions of years old.

I focused on a single star. That twinkling pinprick of light had been birthed in a distant part of the universe, before constantly, tirelessly traveling across great voids to reach a girl one Earth night in the Alaskan wilderness, curled up in a firewood box listening to her family. She would see it and acknowledge its existence and have her own existence, a part of the ever-changing, ever-moving universe, acknowledged in turn.

Had a cannery worker looked up and seen an earlier version of this light? If so, the light connected me to him in time. We were fellow witnesses of the light’s eternal journey to… where? When? Was it going to return from where it had come, like the spawning salmon in the cannery’s creek?

It would continue its journey, speeding in the silent vacuum of space, taking a part of me, this moment, with it. That unknown cannery worker who had looked up and seen the same light was a fellow passenger.

I always felt everywhere I went, in the woods and on the beaches, that somehow some part of the cannery workers who had lived here so long ago were still here, but in their own era, going about a life they’d already lived, but somehow present, too, in our time.

There was a sense of the place being haunted, but not in the usual sense of that word. I didn’t believe in ghosts, but I did think that as long as a person was remembered at least a remnant of them lived on. What was a memory-person who could almost be seen, almost touched, almost interacted with? Was there a technology not yet invented that could free their memory-images from time’s grip?

The cedar shake walls of the wood box surrounded me as I hugged myself to keep warm and stared up into the twinkling sky.

Did time have mirages like space did? Was the Flying Dutchman, I wondered, an example of a temporal mirage?

We owned a large annotated chart book covering British Columbia and Southeast Alaska that all of us, adults and children alike, pored over and discussed. One margin note recounted a sighting of the legendary “ghost ship” in our general area as it was recorded in the logbook of the Alaska State Ferry M/V Malaspina.

Like all log entries, it gave the exact day, hour, position, weather, and barometric pressure: Sunday, 6 a.m.; February 15, 1973; sixteen miles south of Ketchikan, abeam Twin Island in Revillagigedo Channel; unlimited visibility with northeasterly winds at ten knots; temperature 28°F and barometric pressure at 29:71.

Chief mate Walter Jackinsky was standing watch on the bridge with the helmsman and lookout when “a huge vessel loomed up approximately eight miles dead ahead, broadside and dead in the water.” The appearance of it was so striking that they were careful to write down the vessel’s exact position in longitude and latitude, near the south end of Bold Island in Coho Cove, marked by Washington Monument Rock.

The log entry reports: “This vessel strongly resembled the Flying Dutchman. The color was all gray, similar to vapor or clouds. It was seen distinctly for about 10 minutes. It looked so exact, natural and real that when seen through binoculars, sailors could be seen moving about on board.”

As they watched, the ship dissolved and disappeared.

Huddled in the wood box, I wondered: Were the cannery workers a kind of mirage, recorded on the land around us, and on the ruins—the same way that spatial mirages of long-dead people and past events were mysteriously recorded and preserved on film?

I longed to know who they’d been, what they’d thought, how they’d reacted to this lonesome edge of the world. After we were gone, would we leave temporal mirages of ourselves behind, recorded on the beaches we played on, to mingle with the cannery workers?

• • •

Once we settled in, on the protected side of the cannery, we hardly ever went over to the Other Side where the burned ruins were, especially when it was just Mom and us kids. The charred wreckage lined the large salmon creek where the bears roamed, undisturbed by the rusty skeletons of machines. It meant nothing to them that once a mechanized world hummed, pounded, and rumbled in this remote outpost.

In my mind, the Other Side came to feel a bit like the Forbidden Zone in the original Planet of the Apes where the surf washed endlessly against the remains of a destroyed civilization. Yet, though it retained its strangeness and mystery, it still felt like home. I suppose in the same way an ancient castle with a ruined wing can be a home.

Any visit to the Other Side was memorable, but none more so than when Uncle Lance came to stay with us and act as our tutor for a short while after Muriel and Maurice left.

Although technically he was another adult who could be with Mom and us kids while Dad was away during the week, Lance had only recently graduated high school and Jamie, me, and Megan had shared the same classroom with him in the one-room, all-grades bush school in Meyers Chuck.

He was born late in life to Mom’s parents—Mom was a teenager during his preschool years, and while her parents worked she raised Lance. When Jamie was born, Lance was more like an older brother to him than an uncle.

I have few memories of him teaching us, probably because we didn’t see him as a teacher since he’d only recently been a classmate. I doubt he took the position seriously himself, but being of an artistic bent he did enjoy teaching us from our art history books. One time he took us on a school field trip into the woods to find leaves and ferns to use in sponge painting and stenciling art.

He was well read with a large, picturesque vocabulary and wised us up less through direct teaching and more through incidental moments. Like the time Megan was appalled when Lance mentioned that he was going to take a “spit bath.” She let it be known that she thought anyone who would bathe in spit was just plain gross. Lance, swallowing a grin, explained that a spit bath was one that used little water.

Coming to live in Union Bay with us at the old cannery site was a boon to him—jobs were scarce, and it allowed him to get out on his own. Sporting the long-haired hippie look, he turned the wanigan into a smoky man cave where he could blast his screaming Seventies music so loud the cannery workers probably heard it after it tore a hole in the space-time continuum.

Still, he had a knack for knowing what music suited other people’s tastes.

Every now and then Lance would cross the beach in the evening, his boots crunching on gravel, seeing by the moon, starshine, and the lamplight falling out of the wanigan’s windows on one side of the beach and the floathouse’s lit windows on the other side. He’d burst in on us while we were playing board games with Mom (Chinese Checkers, Sorry!, Yahtzee, Monopoly, Risk), or when she was reading a book to us before bed (Down the Long Hills, Little House on the Prairie, Five Little Peppers, The Hobbit, “The Wanigan Kids”).

Lance attended the same one room school as we did in Meyers Chuck and was more like an older brother than an uncle.

Without so much as a greeting, Lance would insist, “You have to hear this!” He’d go straight to the car stereo that Dad had rigged inside the floathouse to a marine battery and shove a cassette in.

We’d sit at attention for the entire album, completely absorbed by the music in the yellow lamplight: Kim Carnes with her broken, rusty voice sang “Bette Davis Eyes,” or Shot in the Dark’s inspired guitar/flute duet on “Playing with Lightning” chimed out. We immediately fell in love with and played these albums, and others he introduced us to, on endless repeat until they became the soundtrack to our wilderness life.

During the daytime he and Mom had lengthy discussions about the books they were reading. Though in Lance’s case, it wasn’t exactly a discussion. He’d give a blow-by-blow account of his book. He’d follow Mom around the house, describing every scene with photographic clarity, following her down to the bathroom, despite her laughing protests, where he’d continue his rant outside the door. There was no escape.

Or he’d come over to share a long-winded, off-color joke that Mom would do her best, to no avail, to head off at the pass. Or he’d entertain us kids by producing the sound of flatulence with nothing more than his hand in his armpit, working his arm industriously. The boys were deeply impressed. Another time he came over to bedazzle Mom with an illusion where he turned his back to her, wrapped his arms around himself, and managed to conjure a woman madly in love with him.

He and Mom also loved playing “Name That Tune.” While we watched, they took turns putting a cassette in and allowed a song to play only a snatch of music. They were both good at recognizing who the artist was from the barest riff, but Lance usually won in the end. He was merciless with his disgust and disillusionment when Mom missed one, though she just laughed.

After he left the wilderness to live in the city of Ketchikan, he never forgot us and sent out mixtapes with the latest hits: “The Breakup Song” and “Jeopardy” by Greg Kihn, “Physical” by Olivia Newton-John, “Seven Year Ache” by Rosanne Cash, “Morning Train” by Sheena Easton, “Don’t Go Breaking My Heart” by Elton John and Kiki Dee, and so on.

He also recorded directly off the radio, particularly channels that offered a “blast from the past” line-up of hits from Mom and Dad’s youth. Through these albums of Fifties and Sixties songs, our parents’ era also became a part of ours. We heard these songs at least as often as the modern Eighties ones.

The most memorable recording that Lance sent out to us was Jeff Wayne’s rock opera of HG Wells’s The War of the Worlds, brilliantly narrated by Richard Burton. We never tired of listening to it. We sang the songs from it while we played in the woods and on the beach. Megan and I, with doubtful harmony, crooned “No, Nathaniel, no, there must be more to life” at the drop of a hat as we rode pretend horses around the beaches and built our forts in the woods.

And, with ghoulish relish, all of us intoned the eerie Martian war cry: “Ulaaaa!” It rang off the fortress-like wall of trees and the shore-lapping bay at all hours. We loved to do it at least in part because Mom hated it; she tried to ban it, with zero success. Creeping her out added to the entertainment value.

The story of Earth being taken over by aliens, torching civilization with their death ray, resonated with us almost as much as it had terrorized the victims of Orson Welles’s infamous 1938 radio play. While his audience believed it to be a real, live program and panicked, racing away into the night in a mad scramble for survival or stuffing rags in the cracks of doors and windows to escape the fumes of the Martians’ deadly poison gas, the five of us kids listening to a recorded rock version of that show nearly half a century later could have easily been convinced that it was true.

My parents could have told us that the world had been destroyed by an alien race or nuclear warfare, with only a few pockets of humanity surviving on Earth, and we would have believed it—because we saw nothing around us to disprove it, and plenty to suggest it was true.

The Other Side seemed to confirm it.

• • •

While Lance was staying with us, he and Mom cooked up an expedition to the ruins.

Unlike our practical, work-oriented father, Mom and Lance were fascinated in a purely aesthetic sense by the atmosphere of the ruins. Their excitement about the illicit trip into ceded bear territory infected us kids. Though they were both adults, Dad’s influence tended to dampen risky, arty whims even when he wasn’t there. The sense that we were on a covert trek only added to the thrill of it.

We set out into the forest. The narrow dirt trail was marked here and there by giant moss-covered, rotting stumps. At some point in the past the cannery superintendents had fallen massive spruce and cedar trees surprisingly deep in the woods, but for what purpose it wasn’t clear. Had they milled their own lumber to build the boardwalk? Or had they somehow hauled the enormous trees down to the water to be used in making fish traps?

Because these large trees had been cut down in the middle of the peninsula that separated the two sides of the cannery, and many trees had been cleared to put in the wide boardwalk connecting both sides, oddly enough the deeper we went into the woods, the more open and airy and bright it became. There was a strangeness to it, as if we were stepping into a zone where the natural laws of the temperate rainforest ceased to exist.

Porcupines clambered clumsily up slim, young trees that had sprouted in the absence of the big trees’ shadows. Moby barked at the prickly, comical beasts, but after having one dropped on him when Lance shook it out of a tree, Moby learned that he wasn’t interested in a closer acquaintance.

Mom made no effort to stifle our young, high-pitched chatter, believing that human noise warned away bears. She’d attached bells to our life jackets for that purpose and told us to talk loudly, whistle, and generally make a lot of noise whenever we were in the woods. This was one of the mandates of hers that we zestfully obeyed.

The forest was brilliant with every shade of green, the moss a spongy verdant ocean that waved over fallen trees, rocks, and hills. Far below the canopy, giant-leafed, almost tropical, stands of banana-yellow skunk cabbage colonized boggy areas, and shyly curled fiddlehead ferns lined the trail and windfalls in thick profusion.

When we broke out of the woods, we went from comforting color and life to a scene of black-and-white desolation.

Under a leaden sky the ruins were stark. The creek, hidden by the trees, rumbled monotonously. The tide was way out, probably a minus tide, and the blackened pilings stretched in broken rows down yard after yard of rocky beach. Amidst them, the frames of the cannery’s machinery lay where they had fallen decades ago when the floors, decks, and pier were engulfed in flames.

We picked our way through the debris field, like divers exploring a deep sea wreck. The minus tide added to the strangeness. I imagined old-fashioned wooden freighters tied to the pier these pilings had supported, floating far above my head as they took onboard tons of canned salmon.

The abundance of metal in odd shapes appealed to both Mom’s and Lance’s creative natures and they enthusiastically fitted them together into modern art steel sculptures right there on the spot. We kids were encouraged to follow suit, as an ad hoc school fieldtrip.

Back in Meyers Chuck when Lance was fourteen, he and his friend Norman Miller (one of my Aunt Marion’s five brothers) used to act as city architects on the beach building entire metropolises, beginning with a rusted-out starter they found as a town power plant. Inspired by these memories, when Lance investigated the ruins that day with us and saw a rusty bedframe complete with bedsprings and a headboard, all concretized together, he knew that he had to build a car.

He used it as his platform and Mom and the five of us kids pounced on tortured rusty shapes, calling out “car parts” and dragging them to him. We watched in delight as the junk turned into a jalopy, as Mom called it. Lance positioned four huge gears on both sides as wheels, and a wheel valve attached to a long steel pipe as a steering wheel. He built up seats, the hood of the car, and a trunk.

When he was finally satisfied, his collaborators were sweaty and grungy, covered in rust, but elated with the results of their labors and Lance’s vision. Mom lamented not having film in her camera to capture the junk jalopy as it rested on the rocks, far from any road, with the expanse of the bay and the distant mountains of Prince of Wales Island on the horizon beyond it.

Nevertheless, we posed on it, riding in the back seats as Lance drove and Mom took pictures with squared fingers held up to her eye.

“Where should we go?” Lance asked, jauntily honking an invisible horn.

Each of us kids got to shout out a destination and Lance made engine noises. We leaned when he leaned, taking sharp corners around precipitous drop-offs, laughing as the jalopy careened into one imaginary story after another.

The jalopy remained on the beach long after Lance left, eventually scattered by heavy storm surges. It remains in my memory, ready for us to climb aboard and drive off into adventure amidst the cannery ruins.