Читать книгу Raised in Ruins - Tara Neilson - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER ONE

“It’s not the end of the world, but you can see it from here.”

—slogan on T-shirts sold at the Meyers Chuck store

EVERY DAY as a child was an adventure for me and my four siblings as we lived in the burned ruins of a remote Alaskan cannery. Some days had more adventure in them than others. Mail day was a day that promised parent-free adventure.

Our mail arrived at a nearby fishing village by floatplane once a week, weather permitting. We lived only seven miles of water away from the village—there were no roads, or trails—but the route was hazardous, even deadly, because of the mercurial nature of our weather. What had been glassy water an hour before as we made the trip in a thirteen-foot open Boston Whaler could turn into a maelstrom of seething white water an hour later to catch us on the return trip.

Tides, weather forecasts, and local signs had to be carefully calculated before the trip could be made. So it sometimes happened that we would miss several mail days in a row and get three weeks’ worth of mail at once. My parents usually made the trip by themselves, since freight and groceries would fill the skiff, leaving us kids behind in our floathouse home.

Our sense of adventure, always present since our family comprised the entire population of humans for miles in any direction, quadrupled as we waved goodbye to them. We watched them turn into a speck out on the broad bay with the mountain ranges of vast Prince of Wales Island providing a breathtaking backdrop for them.

Then we cut loose. We ran around the beaches, jumping into piles of salt-sticky seaweed and yelling at the top of our lungs, the dogs chasing us and barking joyously. We tended to do this every day, but it was different on mail days. We lived in an untamed wilderness that could kill full-grown adults in a multitude of ways, and we children had it all to ourselves.

At our backs was the mysterious forest that climbed to a 3,000-foot-high mountain that looked like a man lying on his back staring up at the sky. We called it “The Old Man.” In front of us was the expanse of unpredictable water with no traffic on it, except for the humpback whales, sea lions, and water fowl.

As we scattered, my littlest brother, Chris, wound up with me in our twelve-foot aluminum rowing skiff. I was twelve and he was seven, and we were buckled up in our protective bright-orange lifejackets that we never went anywhere without.

“Where shall we go, Sir Christopher?” I donned a faux British voice as I sat in the middle seat with an oar on either side of me. “Your wish is my command.”

He sat in the stern seat and chortled. Whereas I was blonde and blue eyed, he had almost black hair and green-flecked brown eyes. Despite the surface differences, we had a lot in common, being the most accommodating and easygoing ones in our family. Chris was always smiling and I was always reading. We usually let others take the lead, but this time we would make our own adventure.

“I don’t know,” he said. “Where do you want to go?”

I looked around. The floathouse sat above a small stream below the forest, its float logs that made up its raft dry, since the tide was halfway out. Opposite it was a smaller floathouse that we used to go to school in, before our dad built a school for us on land.

The small, sheltered cove suddenly felt restrictive since it was the only part of the old cannery we saw on a regular basis, and there wasn’t much of the old cannery to see, just some pilings sticking half out of the water.

“Let’s go to the ruins,” I said.

He gazed at me raptly. The main cannery site had been built next to the large salmon creek and sat on the other side of a high-ridged peninsula from the little bay our floathouse was in. We rarely got to visit it because the salmon creek was where the bears roamed. But we would be safe in the skiff, I told him.

Chris bounced on his seat and nodded excitedly.

I dug the oars into the silky green water and we headed for the big rock that partially protected our little cove from the storm-prone bay. Mom had made it a law that we were never to get out of sight of the floathouse, but Mom wasn’t there.

I dipped the oars into unexplored waters, rowing past the weathered grave marker of some unknown cannery resident. Tall black bluffs loomed up at the same time a swell rocked us. There was nowhere to beach the skiff now, if we needed to… we were committed to continue.

Chris gripped the aluminum seat and stared at me, silently asking if we were really going to do this. I nodded.

Each pull of the oars took us farther away from the homey familiarity of the floathouse and its confined bay. We were exposed to the full effect of the wilderness now, the enormous sky above, impermeable, towering bluffs washed by waves to our left, and the endless waterways of Southeast Alaska on our right.

My back was to the view ahead of us as I rowed. I was getting tired, but I didn’t want to admit it to my little brother.

Chris sat up straight on his seat and pointed. “Look!”

I turned my head. Up on the rocky bluffs ahead of us was a huge steel cylinder with a peaked roof. Its original, unpainted gray could be seen through the rust of untended decades. It had sat sentinel there, below the tall mountain, with few humans visiting it or seeing it since the cannery burned shortly after World War II.

Awed, we stared at it, and then I turned to the oars with renewed energy. I kept throwing glances over my shoulder. I didn’t want to miss the first glimpse of the ruins.

And then there it was, the old cannery site.

A forest of fire-scorched pilings, one with a stunted tree growing on it, stood between the forest and the bay. The blackened timbers of a building’s foundations remained below the evergreens’ skirts and giant concrete blocks stood out whitely above the rust-colored beach. Amidst the pilings were strange, rusty skeletons of former machinery. The creek rumbled past all of it.

The ruins.

“It looks like it was bombed,” Chris said. “Like an atom bomb was dropped on it!”

“It does.” I tried to picture what it would have looked like when it was whole and people lived and worked at this remote location. The buildings, like all the canneries in Alaska, would have been cannery red (the color of chili peppers) with white trim, glowing in the water-reflected light. The sound of machinery would have competed with the constant rumble of the creek and men and boats would have been working above and around the pilings of the wharf as clouds of shrieking gulls filled the air.

“If we could time travel,” I said, “we could step into their world when the cannery first operated and watch the fish being packed into cases to be sent out into a world that didn’t know atom bombs could exist.”

I didn’t try to row us closer and Chris didn’t suggest getting out on shore. We could see big, dark moving things in the creek that we knew were bears. I didn’t want to draw their attention because, although I didn’t mention it to Chris, I knew they were powerful swimmers and could probably overtake us if they’d wanted to.

We sat in the small skiff with the water lapping against the aluminum sides, rocking in the swell, and gazed at the ruins of a former world, gone long before we were born.

Then I turned the skiff around and we headed for home, promising each other we wouldn’t tell anyone about this adventure.

This one was just ours.

• • •

MEYERS CHUCK, ALASKA

35 MILES NORTH OF KETCHIKAN

SPRING 1980

We were supposed to be a group of intrepid families braving the apocalypse. Our unified mission: to homestead the ruins of a bygone civilization and resurrect and transform them into an off-the-grid, self-reliant wilderness community.

The adults spent long kerosene-lamp-lit hours poring over the maps, studying the remains of the old cannery that had burned nearly half a century ago. None of them had seen it in person, but they marked out where each home would go, the supplies they’d need, the school they’d build. They figured out how they would barge fuel in, what kind of generators they’d need for electricity, if they could arrange a mail drop way out there in the wilderness far away from all human industry.

When I overheard the talk, I felt like I was overhearing plans for moving aboard a generational starship that was going to explore and colonize deep space.

My family of seven in our tiny thirteen-foot Boston Whaler skiff, overpowered by a fifty-horsepower Mercury outboard motor, went alone on the reconnaissance expedition. Together, we would be the first ones to scout the old cannery.

We whipped past the green forest that seemed to stretch from here to the moon as it climbed a ridge on one side. Across the glassy strait was a vast island covered in snow-capped mountain ranges, headland after headland disappearing into a pearly blue distance.

That was Prince of Wales Island where Dad worked as a logger at the largest logging operation in the world. There were enormous bald patches in the dense green hillsides, giving the island a mangy appearance at odds with the pristine, breathtaking beauty of sea, sky, and the unmolested mainland we skimmed along beside.

Our uncovered skiff, about the length of a Volkswagen Beetle, was a speck.

The world was big; I knew that from school lessons. But the wilderness was bigger. There was no end to it. We were the only humans in it as we sped across the gigantic white-cloud reflections. Ahead of us, a mountain lay on its back, a giant Easter Island head with its stern nose pointed toward the sky, toward space, toward the orbiting planets around the sun, and beyond.

And my family was heading toward it and the slumbering ruins that it had shadowed for decades.

I turned my face into the wind, my hair whipping into a knotted mess around my head as I leaned forward. The bearded man with his hand on the tiller handle of the outboard had decided he was going to go to the ruins, and I knew nothing, not even all this wilderness, was going to stop him.

This was, after all, a man who had stopped the Vietnam War. For an entire day.

He told me years later that when he’d just turned twenty-one, married one month, he had arrived in Vietnam during Phase 1 of the Tet Offensive. In the span of twenty-four hours he saw a bustling metropolis, the Asian people living in it as they had for generations, become a bomb-blasted landscape of skeletal buildings and streets filled with smoking rubble.

After seeing the effects of war close-up, one of the first things he did was to build himself and his fellow grunts a sturdy shelter—a bombproof igloo, so to speak—out of cast-off rocket ammo boxes that he directed his companions to fill with sand for the walls. For the roof he used PSP (perforated steel plating) with more sand-filled rocket ammo boxes on top.

No one had thought of building such a thing, even with screaming missiles and mortars constantly overhead. Everyone else sweltered in flimsy tents or buildings with uninsulated steel roofs that acted like ovens. His igloo was the only comfortable building in the muggy jungle heat. He and his friends had it for three months before the officers evicted them and took it over for themselves.

Dad was a helicopter mechanic (the sole mechanic available for the Huey; a group of mechanics serviced the other helicopters) and it was his job to say which helicopters were fit for duty on any given day. Every day some helicopters didn’t come back—and friends and companions disappeared or were brought back bleeding, maimed, or dead. One day one of his best friends was killed.

The next morning he put an X on every single Huey, grounding them all. Without the support of the Hueys none of the other helicopters could fly, and without air support the ground war couldn’t progress. That day he wasn’t going to allow anyone else to die in an ugly war no one really believed in or knew what they were fighting and dying for.

His commanding officer said to him, “You know you can’t do that, Gary. You have to take those Xs off.”

Dad just looked at him. The Xs stayed. There was no war that day. Across from him in the back of the skiff, hugging her youngest child, Mom couldn’t believe she was there, that she was living her childhood dream of Alaska as few people had ever gotten to experience it.

Despite her obsession with fashion, music, the arts, and her dream to become a Parisian club singer, she had always felt a fey-like affinity for wild creation and the animals in it. As a teenager she’d gone for day-long walks in the rural Montana countryside with her Belgian Shepherd named Gretchen, spinning dreams out of the Big Sky sunshine.

In her own words:

“We lived on a ranch high in the hills. I would get up early, have breakfast, feed Gretchen and the horses, then I would sit my record player on an old wooden chair on the porch, put my Bob Dylan album on at ‘Like a Rolling Stone,’ and Gretch and I would go, hearing the music all down the old dirt road.”

Her most thrilling moment in her dawn-to-dusk rambles with Gretchen was when the deer came over the mountain.

“It was a large group of deer—until that moment I hadn’t realized that they would all travel together like that. Bucks, does, and babies. They all came straight to where Gretchen and I stood, quivering. I stretched out my arms to them and they walked quietly on both sides of me. Not as if I wasn’t there, but as if they understood that I belonged to, and with, them.

“I stood there with my arms outstretched for quite a while as the herd passed on either side, my hands on their backs as they went by, one by one, my hands sliding along backs and haunches. Bucks, does, fawns.

“They felt like… ‘alive’ feels. The only alive I wanted to be. I never wanted anything so much as to turn and go with them…”

And now here she was an adult, with her husband, a man she barely knew after Vietnam—they’d married one month before he went, and the man who came back was not the funny, laughing man she’d married—and five children, heading into the heart of the most remote country she’d ever seen, setting out on an adventure to rival any adventure or experience she’d ever had or read about. She was so excited she was shivering.

• • •

How was I to know at nine years old that this journey, toward the Old Man mountain staring up at eternity, was to become one of the favorite things of my entire life? I never imagined on our scouting trip how many times I would make it, with my family or alone.

In the skiff, the loudness of the outboard and the wind whipping at our faces made it hard to hold a conversation, so each of us retreated into our own private worlds. On every skiff ride to the cannery, I’d sink down turtlelike into the canvas-over-foam shell of my lifejacket for its comforting, tight embrace, and chew on its black plastic piping, salty from seawater. From this haven I’d look around at the dreaming faces, at the interior eyes, and I’d wonder what each person in my family was thinking as we rode silently through time, from one world point to the next.

We would always start in a place of daily bustle, of talk, of goals and intentions. Then we’d climb into the skiff, and within minutes we were in our own solitary time-out bubbles surrounded by the steady engine noise and the sky and water, suspended from human interaction until we reached the other world point where goals and talk and intentions continued. We might as well have stepped onto a transporter pad and had our constituent parts disassembled and then reassembled on the other side of the skiff ride.

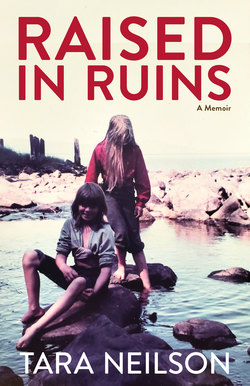

Jamie and I in the front of our Boston Whaler on the very first trip to the ruins.

Besides my parents, on this particular skiff ride there were “the babies” as we still called them, my two little brothers, sardonic Robin (five) and smiling, generous Christopher (four)—or Mitmer-the-Usurper, as Robin thought of him. Chris had displaced him as the baby of the family and the natural center of attention and affection. (“Mitmer” was Robin’s pronunciation of Christopher and soon the whole family used it.) Robin, clever and stubborn, never let anyone forget the wound of this usurpation and the babies spent all their time butting heads, wrestling, and punching.

Then there was Megan (eight), my sister, best friend, and closest companion in age. People thought we were twins since we rarely did anything apart and we were both fair haired with blue eyes. Megan was artistic and sensitive, so softhearted that one time when she stepped on a slug on the narrow gravel trail as we were on our way to school in Meyers Chuck, she had to turn back. Though we were almost to school, she retraced her steps and put the slimy, squished bug out of its misery, all the while sobbing bitter tears.

Her polar opposite was Jamie (eleven), the oldest, who had been born when Dad was away in Vietnam, who had in infanthood considered himself the man of the family and had never known how to stand down from that patriarchal position after the real man of the family returned. Jamie had coopted all of Mom’s time, attention, and affection from birth and wasn’t shy about letting the Intruder—who Mom called “Gary”—know who ran the show.

When Dad would take his wife and small son to dinner at a friend’s, Jamie would decide when it was time to call it a night. He’d put on his outdoor clothes and plant himself in front of Dad and announce, “I’m weddy, Gowwy.” If Gary should, inconceivably, ignore him, Jamie would make himself more visible and raise his voice: “I said I’m weddy, Gowwy.”

This assumption of authority in his small son didn’t go over well with a man who was struggling with PTSD, the demands of a ready-made family, the cold callousness of some of those close to him who made it clear they had no use for Vietnam vets, and the requirements of holding down a job and providing for his family.

Whether it was caused by Dad’s antipathy or not, Jamie developed an interest in torturing those around him and then studying their reactions. Once, as a preschooler, he rigged a hallway with fishing line and watched as Mom became entangled and struggled like a fly caught in a web. Another time an older kid came over to play with Jamie when he was two. Moments after Mom left them together, she heard the neighbor kid yelling that he wanted to go home. When she went to check to see what was happening, the boy was rattling the kid gate, demanding to be freed. He couldn’t explain what had happened and Jamie just stood in a corner, smiling.

It was a smile we all learned to dread.

And me? Some of my earliest memories, when I was three or four years old, are of getting up every night to pad to my parents’ bedroom door. I would step inside and listen to them breathing. I remember the need to do that, to make sure they were both okay. One of them because he was broken, and the other because she was unknowing.

I couldn’t bear for anyone to feel diminished and humiliated, to experience loss, for anyone to suffer. Mom tells me that when I was two or three she read me a story about a baby horse that overcame becoming an orphan to live a happy life. At the end I was sobbing. She was bemused. “What’s wrong, honey? It’s a happy story—see the little horse grew up to be strong and happy!”

“But the mama horse is still dead,” I sobbed.

Now, at nine years old, I was the family observer, the mediator, and the chronicler of all of our adventures.

• • •

The Union Bay cannery operated at the mouth of Cannery Creek on the eastern shore of Union Bay, which is located on the east side of Lemesurier Point at the southern entrance to Ernest Sound. It existed about halfway between the cities of Wrangell to the north and Ketchikan to the south, and was unable to be reached by land, only by water and air.

Local fishermen sold their catch to the cannery, which then sold in bulk to Japan. In the 1920s there was a saltery for mild-cured king salmon and later a herring reduction plant and floating clam cannery that operated seven miles away by water in Meyers Chuck, on the west side of Lemesurier Point. In pre-WWII years, Meyers Chuck’s over one hundred residents supported a post office, store, machine shop, barber shop, bakery, and bar.

Both the cannery site in Union Bay and the fishing village of Meyers Chuck are on Cleveland Peninsula, which is a part of the mainland. The Coast Mountains, with all their glaciers and snowy ramparts, separate the peninsula from Canada.

Their location on the mainland is unusual. Most communities in Southeast Alaska are on islands. The Cleveland Peninsula terminates at Lemesurier Point, which juts into Clarence Strait, a feared branch of the Inside Passage, and stands across from Prince of Wales Island where one of the few road systems in Alaska’s Panhandle connect a variety of small towns.

The cannery had been built in this isolated place in 1916 by Union Bay Fisheries Co., going through two other owners before it was sold to the Nakat Packing Co., which was owned by the son of the Norwegian founder of the city of Petersburg and a partner. They owned it until it burned in 1947.

Burned canneries were not an uncommon sight in Southeast Alaska. Between 1878 and 1949, 134 canneries were built. Sixty-five burned and were never rebuilt. Ours was one of them.

The few photos Mom has of our first day at Cannery Creek are gilded with sunshine. We’re in our lifejackets, discovering the miracle of that rarest of all rare embellishments in rocky Southeast Alaska—a true sand beach.

Above it are the usual seaweed and barnacle-covered rocks. In the photos Dad is behind us kids as we explore; he’s pushing the skiff off and anchoring it in the current of the creek so that it won’t go dry as the tide recedes.

Jamie’s dog Moby is out of the frame: he’s already taken off, nails clicking and scratching over the rocks, to do his scouting ahead of us. Jamie is watching over the two little ones while my sister and I stand together out in front. The bay stretches out behind us kids and Dad to a shimmering, hazy horizon, as if we’ve stepped through a curtain into another dimension, into a different experience of time.

The ruins of the cannery were on the other side of the creek from us. Dad had decided against landing the skiff there since fallen machinery littered the entire beach and could extend for some distance underwater. He didn’t want to foul the outboard’s propeller, leaving us stranded.

Once Dad secured the skiff, he led our family up the sandy beach and into the rocks.

The limitless forest of cedar, spruce, and hemlock lined the creek. Evergreen scents sharpened the air over the sun-warmed beach grass. The amber-colored creek, pierced with sunshine, tumbled over the stones and boulders, rushing past the rocky bank we stood on. Up a ways, on this side of the creek, a small cabin dappled by the shadows of alders was the sole building left standing. Its faded red paint was the color of Southeast Alaska’s historical canneries.

Opposite us, on the other side of the creek, we could see the ruins of the cannery proper, with its broken and blackened pilings and giant, rusting fuel drum on a point of rocks. Great chunks of weathered concrete stood in the creek between us and the ruins. They stood against the flow, refusing to crumble to the doublebarreled forces of time and water. They had probably once supported and anchored a bridge.

Megan and I in the front, Jamie and the boys behind us with Dad anchoring the skiff in the creek’s current as we first set foot on the old cannery site.

When we got to the edge of the rushing creek, Mom and Dad carried the younger boys from stone to stone in the shadow of these concrete monoliths of a long-gone world, telling us older kids to be careful as we followed. Moby, a Sheltie with a touch of Cocker Spaniel, ran ahead, pausing and looking back with a panting grin from every dry perch.

I wonder now at our lack of fear as we tackled that abandoned place, where the bears, both black and brown, had reigned unopposed for decades; where there was no hope of help, no one to hear us or come to our aid if we were harmed.

Instead, we pushed forward, all of us, eager for this exploration. And the ruins? They’d been there a long time… waiting.

This had once been a community, as many as a hundred men and women living here cut off from the world, telling their stories, thinking their thoughts, dreaming about their futures. They played cards, drank, danced, sang, and worked and worked and worked as the cannery rumbled, with fishing boats and freight boats coming and going. And in the background the unending thud of the pile driver pounding in pilings for piers and fish trap.

This was a place that had known people, that had made room for them. But after the fire, after the scars and disfigurements, the people had left. For many silent years this place was visited infrequently by fishermen and by locals who came to scavenge—who sawed off what was still good of the burned pilings that had once upheld the wharf and cannery and towed them away to use as foundations under their village homes.

The Forest Service had also been there shortly before us. They’d been surveying the area for a possible logging project. They’d built a sauna beside the foundation beams of a building that no longer existed, and laid down boards to perch their pre-fab temporary shelters on. But in the end, they left too, taking the pre-fab buildings with them but leaving the sauna and the planks behind.

US Steel, the company that had bought the property after the cannery burned, had checked for profitable ore and, finding the extraction and transportation expenses cost prohibitive, abandoned the venture. They left behind a rock pile and stacks of core sample holders in a core shack, and up on the mountain concrete pads, cable, and other debris.

The ruins had watched and waited for life to return, for people to return for real. I felt that as we wandered through the scorched and blackened remains. I felt that we were being welcomed and encouraged to stay, that the ruins wanted us there.

We accepted the invitation and made ourselves at home. We kids could not be dissuaded from stripping down and swimming in the creek, though it was so icy it burned, fed by mountain snows. Our shrieks and laughter floated out over the twisted, rusting metal on the beach, over the solid concrete blocks barren of their former buildings, over the cannery’s retort door, its giant rusty circle half-buried in beach gravel.

When I left the water behind, shivering, teeth chattering, it was to find Mom standing in the ruins beside the creek. All around her were stark foundation pilings and rusty steel frame beds, twisted into agonized shapes from the intense heat.

The forest had taken over everything, underbrush and strangling second-growth growing rampant over what had been the bunkhouse, where only rotten boards and foundation pilings remained. Yet she stood there visualizing aloud in word-pictures what our future house, almost a mansion, would look like.

“Which bedroom would you like, honey?” she asked me, as if it were already built.

I stood there looking at the overgrown apocalypse and wondered at her ability to see the same thing and not notice the practical impossibilities of what she was saying. It felt like sheer, breathtaking madness to make real her grand designs out there on the edge of nowhere with her children and husband for skills and labor.

Dad, listening silently from behind his glinting glasses and the beard he’d grown in defiance of the clean-cut conformity that had sent him off to war, noticed the obstacles. But he considered them a challenge and saw the practicalities, not the impossibilities.

• • •

The cannery’s wide-open view of Union Bay meant that it was pummeled by savage northwesterly storms—something we discovered within hours of our arrival.

At first it was cat’s paws ruffling the bay. Then little wavelets lapped at the ruins as the tide rose. The wavelets transformed into a rushing, curling crash of heavy surf as the wind thrashed the evergreens and careened through miles of forest with a rising, freight train roar.

Dad fetched the skiff from where he’d anchored it and tied it to the remains of a Forest Service outhaul: a rope and pulley system that allows skiffs to be kept out in deep water so they don’t “go dry” (beach on the ground as the tide recedes), and can be pulled in as needed.

There was no way our little thirteen-foot open skiff could battle against the expanse of white-capping rollers marching toward us as the afternoon gave way to dusk. We were stranded, marooned in the shadowy, burned ruins without food, bedding, or shelter.

• • •

I don’t know how you’re supposed to feel about being marooned beyond the last fringe of civilization, beyond help or assistance. Fear seems appropriate, or at least unease, a troubled awareness of all the ways that two adults and five children could die alone and disappear in the wilderness.

My parents set us to work on clearing the land where Mom visualized having her home built, next to the creek, since she’d always dreamed of having a home near rushing water. As Dad chopped seedlings and undergrowth, we hauled them down to the beach in a big pile, working up quite a sweat, not to mention hunger.

We tired finally, and as the wind blowing in off the bay chilled the sweat on us, we huddled together for warmth. Shivering amidst all those reminders of the destructive power of fire, that was all any of us wanted at that moment: a good, rousing blaze.

We had no matches or lighters since neither of my parents smoked, but Dad did have his .30 carbine with him. The gun was a concession to the dangers of the wilderness, a concession made despite both of my parents’ issues with guns.

Dad was reminded of the war, and Mom had never gotten over her first introduction to firing a gun when she was a teenager. She hadn’t gripped it tightly enough and the recoil had caused the gun to fly up and strike her in the forehead. The pain and shock had been magnified by the deafening report. She’d developed a terrified aversion to all guns to such an extent that she would shake when she was near one and grow sick when she had to handle one.

We watched as Dad ejected a shell and used his pocketknife to dig the bullet out. In a place protected by the wind, behind the pile of brush we’d collected, he dumped the powder onto a rock with dry sticks and moss ready to catch fire. He put the cartridge back in the chamber and fired the primer at the powder, hoping to spark it into flame. However, it blew the powder off the rock.

Eventually—almost, it seemed to us kids, inevitably, as if the elements had no choice but to yield to his angry determination—he got flames to devour his kindling. Now we had a fire to warm ourselves, though nothing to cook on it.

We slept that night in a shelter Dad put together from planks and plastic sheets scavenged from the Forest Service’s leftovers. It was cold, with the wind roaring and the trees cracking and thrashing their branches against each other. The wind switched to the south and it rained in the night. Megan and I were envious of Jamie, who had Moby lying on his feet and keeping him warm. The boys were put in the middle and slept warm and toasty. Mom cuddled the boys, wide awake, too amazed at where she was and the adventure she was living to sleep.

Dad also got little sleep, getting up to check on the skiff as it rode the waves too near the rock cliffs for comfort, the big swells coming in and dashing the small craft forward, only for it to be yanked up short by its line tied to the outhaul. He tended the fire, hunkering down near it for warmth, waiting for first light, for the ruins to come back into focus. Despite the stress of worrying about the skiff, at least he wasn’t being shot at, and the scream of incoming mortars was far away.

We returned to the fishing village the next day, but the ruins called to us.