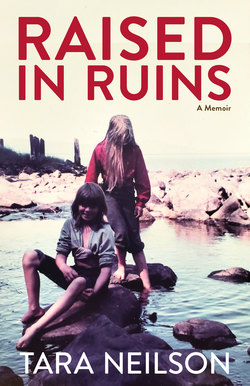

Читать книгу Raised in Ruins - Tara Neilson - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

ONE DAY when it was just my mom and us kids alone in the New House we’d built in the wilderness with our own labor, with lumber our dad milled himself, a huge brown bear paced back and forth in front of the wall of floor-to-ceiling windows in our game room where we spent most of our time.

Back and forth, back and forth, it paced agitatedly, disturbed by our presence next to the salmon-choked creek. Our mom was terrified of guns, but she got down the .22-250, which she probably couldn’t have shot if she tried, and told us kids to go upstairs. We ignored her.

We figured if the bear broke in we’d all scatter and the bear might get one or two of us, but he wouldn’t get us all. Our tension escalated as the huge mound of fur, teeth, and claws continued its angry pacing. Finally he rounded the house, going around the kitchen to the front where our temporary door was made of thin pieces of wood and plastic. If it just sneezed, the bear could break through it.

We followed it from room to room, our hearts beating uncomfortably hard. Finally, we saw it head down to the creek. With the gun in hand, Mom stepped outside to make sure it kept going. She told us to stay inside, but, again, we ignored her.

Suddenly my youngest brother, Chris, took off after the bear.

“What are you doing? Get back here!” Mom whisper-yelled, afraid of alerting the bear. She gripped the gun helplessly. “Christopher Michael! Get back here, right now!”

Chris kept running, gaining on the bear.

The rest of kids stared after him, shocked. When no one moved, I sprinted after him. In front of us the huge bear lumbered toward the shining creek filled with salmon fins and sea gulls. This is crazy, this is crazy, I thought as I ran toward the bear.

I collared Chris, and dragged him back. He fought me every inch of the way. I cast glances over my shoulder, sure the bear would come after us and shred us to pieces in front of our family. The bear turned at the noise and raised itself onto its hind legs, sniffing the air and peering at us.

Fortunately, we all escaped a mauling that day.

• • •

There are many, many more stories like this that I couldn’t include in this memoir due to lack of space. I had to leave out almost all of our adventures we had with the kids in the village of Meyers Chuck, and at the all-grades bush school we attended there for several years. (Note: some of the names have been changed of the people I do write about.)

I wish I could have spent more time on one of my favorite people in the entire world, my Grandma Pat who lived in the village, a woman who had lived a life of constant adventure, who had a wonderful sense of the absurd and chuckled when we dubbed her “Grambo.” I wish I could tell you more about my Uncle Rory and Aunt Marion, who were an influential, wonderful part of my childhood. Or Steve and Cassie Peavey, Alaskans to their core, and owners of the floathouse before my grandparents had it and sold it to us. There are so many important and beloved family members and friends I couldn’t include.

The only way I could let those essential people and stories go was to promise myself I’d write a second book, which I hope to do.

• • •

To this day I don’t know why Chris ran after the bear. I haven’t had a chance to ask him. I think I’ve worn out my family asking them to comment on cannery experiences for this memoir. You will find that family members sometimes comment in the present tense in these pages, because our experiences in the ruins imprinted so deeply on us that they are still a part of our present and continue to shape who we are.

The past felt just a step away for us as my brothers and sister and I played on the scorched, rusting remains of machinery that had operated in a different era, a different world. The former workers always seemed to be present in a benign, welcoming way that made me want to cross over between my time and theirs so I could get to know them.

Because the past and present were melded together it was easy for me to include the future as well, and acknowledge the moment-by-moment passage of time that created my personal experience of life and shaped my personality.

Ever since I was young I have visualized my personal time as flowing from the future to my Moving Now, like the snow-fed headwaters of cannery creek rushing down to meet me as I played in it and as the salmon, according to their own inexorable sense of time, swam beside me, pointed toward their ancient spawning beds.

Whatever the current brought I needed to decide how to react to it, and when I did there were consequences that became my present and then my past, creating who I was and who I would become.

When friend and author Bjorn Dihle suggested I write a memoir, I hesitated. I didn’t think I could capture what it felt like to grow up in the ruins, what it had been like to experience and be shaped by the mystery and richness of Time. But I decided to attempt it.

I soon realized that I couldn’t write my memoir in the linear, chronological way most of the memoirs I’d read were written, so I decided that I’d show as well as tell my personal experience of time. This meant structuring it in a way that might be alien to others who were shaped by an urban view of time, but felt organic to me.

It has given me a sense of closure, because at the age of seventeen I went to live for a year in the world and was shocked and alienated by how time was viewed and used in the city. Writing this memoir and reading theoretical physicist Lee Smolin’s 2006 book The Trouble with Physics has helped me to reconcile and understand my reaction.

Smolin wrote that one of the fundamental problems with physics today that was preventing forward progress to be made was scientists’ understanding of time. He traced the problem back to the beginning of the seventeenth century when Descartes and Galileo graphed space and time, making time a single dimension of space. Essentially spatializing time, stopping its motion and freezing its elusiveness, so that scientists could to some extent comfortably regulate and measure it like they did space.

But when time is spatialized, it becomes static and unchanging. This, of course, doesn’t reflect our lived experience of ever-changing, ever-flowing time. Smolin called this “the scene of the crime.” He believed it was imperative that science find a way to unfreeze time.

Straight out of the ruins, during my year in the city, I saw the spatialization of time firsthand, the frozen quality that Smolin would later point to as a crime. Clocks were everywhere: in school, the library, restaurants, and stores. Time was expected to behave itself so that people could use it to schedule and organize every moment of their lives. With chaotic elements frequently dominating every other aspect of their lives, they wanted no part of time that wasn’t straightjacketed and fixed in place.

I felt smothered and took long walks into whatever part of the wilderness the town hadn’t covered with asphalt, trying to coax the real, wild and unrestricted time out of wherever it was hiding. Later I would return to the wilderness and embrace time in all of its fullness with a sense of relief.

I realize that the way this book is written might feel jarring at times, and uncomfortable for readers who expect a memoir to be linear rather than having the future making unexpected appearances to comment on the present action of the past.

I do apologize. I know how hard it was for me to accept the way most people have lived time: neatly ordered and well behaved, trained to subjugate itself to society’s needs in order to make stressed people feel comfortable and in control.

But in an era that celebrates diversity and encourages all of us to expand and free ourselves from our frozen biases, maybe it’s time to unfreeze society’s interpretation of Time and allow it to be all that it can be.

Please come with me on a temporal adventure as I show you what it was like to be raised in ruins.