Читать книгу Raised in Ruins - Tara Neilson - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER FIVE

A friend: What’s the song that spoke most to you as a child?

Me: “I’m So Afraid” by Fleetwood Mac.

THERE WAS a lot to fear where we lived, and while all of us kids were afraid of bears and storms, each of us had specific things we worried about. Megan and the boys were afraid of the dark. Jamie was afraid of wolves. And I was afraid of burning to death in my bed.

My fear emerged as a result of Jamie’s interest in science.

As a teenager Jamie became obsessed with fantasy, but during his preteen years when we first moved to the cannery the only books he was interested in were scientific ones. “Don’t give me anything that isn’t true. I want fact books,” he insisted to Mom.

Jamie, regrettably, misused his wide-ranging collection of scientific facts.

Like the night Jamie, Megan, and I were playing in the back bedroom by the glow of the kerosene Coleman lantern hanging from the ceiling with a round soot spot above it. Megan was subject to night terrors and had to have the light on all night, though when everyone was in bed my parents turned it down to a mellow glimmer. The long, eight-paned window that faced the forest was black with night, reflecting back an image of the room with us in it.

To stop Robin and Chris from bothering us older kids, they were restricted to one walled-off corner of the large room. Because Mom was softhearted and she didn’t want them to feel left out, she had Dad not panel the wall to their room so they could look out on us older kids as we played.

The unintended result was that the boys looked like they were zoo animals in a wooden cage or enclosure. They loved to scamper up the framework of the open walls and perch at the space at the top, peering down at us, heckling and jeering at us, and throwing their toys at us, like feral monkeys.

This particular night Jamie, Megan, and I were playing Jamie’s own special version of poker in which the rules—forever after immortalized as “Jamie Rules”—were complicated and subject to change without notice. And, let it be noted, always resulted in him winning. Years later I saw the original Star Trek episode “A Piece of the Action” and recognized Captain Kirk’s “Fizz-bin” as Jamie’s version of poker.

As Jamie was explaining to me why I couldn’t make the exact same discard he’d made moments earlier (a spade could never be discarded when a club was turned up, unless a heart had been discarded three turns previously; or if it was a Friday night), he paused and stared at me without blinking.

I shifted uneasily, dreading the appearance of one of his disturbing smiles.

The smile didn’t appear. Instead, his stare became more and more clinical. I did not find this a reassuring development.

“Interesting,” he said. “Did you know that the way some people store fat on their body can be evidence of a lethal combination of chemicals in the stomach? Hold out your arm.”

Warily, I looked at my arm.

He picked it up, squeezing it experimentally. “Uh-huh. That’s what I thought. You have the thick-skinned subcutaneous fat layer profile of the type of person who is scientifically most likely to suffer from spontaneous human combustion.”

I looked at Megan. She stared back at me wide eyed. She looked glad that she didn’t have a thick-skinned subcutaneous fat layer profile.

“What, you ask, is spontaneous human combustion?” he continued in a professorial tone as he shuffled the cards. “It begins with a steady increase in temperature due to self-heating reactions caused by chemical processes in the stomach, followed by thermal runaway. This self-heating accelerates to higher and higher temperatures until finally… auto-ignition.” He dropped the cards and shoved his hands widely apart, miming a conflagration. He added sound effects of a fire burning.

I knew it was better not to understand what he was talking about. I always regretted asking him to explain. “You haven’t dealt out yet. Mom’s going to tell us to go to bed pretty soon.”

He picked the deck back up and dealt the cards out with slow deliberation as he kept his eyes fixed on me. “That means you ignite and burn hotter than a furnace. People who spontaneously combust burn so hot that there’s nothing left of them but their hands and feet. The furniture they’re on barely smolders, but the person burns up completely.”

I pictured Megan waking up one morning, in the bottom bunk we shared, with my hands and feet lying beside her. At least she’d barely be singed.

“What can I do about it?” I picked up my cards, trying to keep it casual. Fear was like blood in the water to Jamie.

He consulted his science books. After a while, as I waited with outward composure, he slapped the book shut. “Nothing. There’s nothing that can be done. You’re one of the rare subsets of humans born with the body type that leads to spontaneous combustion. Science has no cure.” He stared at me for another long, clinically interested moment, then shrugged. “So, how many cards do you want?”

I lay in bed that night, staring at the glowing lantern and the shadows in the corners of the room, listening to the even breathing of my brothers and sister. The window, so close to the woods, always unnerved me at night. It seemed an unnecessary, open invitation to every bear in Alaska to come in and enjoy a midnight snack.

Many a night I’d lie there and hear a deliberate, crunching sound, like footsteps in hardened snow, and I’d try to convince myself that it was my heartbeat, not a bear prowling around, sniffing out its next meal.

That night I heard the rhythmic sound go faster and faster. It was my heartbeat all right, and it was laboring so fast and hard that it seemed to shake me in the bunk next to Megan. Was this the first sign of spontaneous combustion? Sweat popped out on my brow and

I went rigidly still. There was no question now: I was getting hotter.

And hotter.

The more I thought about it and tried not to get hotter, the more heated my body became.

I stared in fascinated horror at the flame burning at the end of the wick in the lantern. My subcutaneous fat layer would make me burn like that wick. I’d char to crusty blackness right next to Megan as she slept obliviously.

Why me? What had I done to deserve a subcutaneous fat layer? Tears leaked out of my eyes as the heat built upward, right into a ball in my throat.

The silence of the house, of the wilderness outside, turned an indifferent eye toward my sufferings as the furnace inside heated to the point of inescapable ignition. I think I passed out from terror.

The next morning Jamie leaned down from the top bunk to do an inspection.

“Oh. You’re still here. I thought you might have spontaneously combusted and I wanted to make a record of it. For science.” He considered. “Oh, well, there’s always tonight.”

He smiled. That smile.

• • •

I was about four or five when my parents took us three older kids—the babies not being born yet—to the theater to watch The Wilderness Family (as it was originally titled when it was released in 1975), during the height of the Back to the Land Movement.

It’s the story of a family that leaves smoggy Los Angeles to homestead remote mountain territory beside an alpine lake, reachable by floatplane. There’s the dad, Skip, a denim-clad construction worker who can’t hammer a nail in to save his life; Pat, a long-haired, too-glamorous-for-my-gingham-skirt former beauty pageant runner-up as the mother; Jenny, the earnest, asthmatic blonde girl who needs to escape the smog to survive and should have won an Oscar for her performance; and Toby, the giggling little boy who gets into generic mischief and has to be surreptitiously elbowed to remember his lines.

The movie is low budget, with endless images of innocent wilderness play set to saccharine songs and back-to-back montages of DIY cabin building and homesteading to save on paying a scriptwriter. Half the dialogue sounds adlibbed on the spot.

The little girl looked like a cross between my sister and me. I promptly identified with her to the full of my preschool heart. There she was on the enormous screen, playing with the wildlife, running joyfully through wildflower-strewn fields in her Seventies bellbottoms, wearing the exact same ribbed tank top I owned, her long blonde hair waving behind her.

Then, all at once, there she was, being chased by a huge, roaring grizzly. In one of the most traumatic instances of my entire life, I watched as the little blonde girl splashed through the creek and desperately hid in a shallow cave. The bear was on her in an instant, clawing at the roots and reaching for her as she screamed for her mother…

Mom says that my sister and I had cowered in her arms and refused to look at the screen until the bear was chased away by the faithful family hound, Crust, the only real hero of the series.

This was my introduction to bears. A few years later my family moved from the Lower 48 to Alaska, to a location eerily reminiscent of the one in The Wilderness Family. We reached it by floatplane. Everyone used a radio to communicate, like they do in the movie. My parents were talking about going farther out to homestead the wilderness.

And there were bears. Everywhere.

Not that I saw one immediately, but they were one of the most frequent topics of conversation amongst the adults. I overheard blood-chilling, hair-raising tales that brought back that terrifying image of the little blonde girl racing for her life as the monstrous beast loped after her.

I suffered nightmares about bears every night of my wilderness life, when I wasn’t hyperventilating over the possibility of spontaneously combusting. Sometimes I dreamed of both. It did cross my mind to think that it would serve right whatever bear crashed through the window and into our bedroom to snatch me out of my bunk if I spontaneously combusted in its belly like a bomb.

I’m sure Mom had her own nightmares. After all, during the weekdays while Dad was away logging, she was responsible for five kids who weren’t known for their adherence to all the rules she dreamed up to keep us safe.

The cannery site was a veritable bear magnet with its large salmon-spawning creek. And, since the site was part of the mainland, we got both black and brown bears. (In the Alexander Archipelago of Alaska, bears practice island segregation—all the brown bears on one island, all the black bears on another. The mainland was a desegregated zone, and we were right in the middle of it.)

Mom had heard all the bear horror stories too, but her fear of them warred with her more visceral terror of guns that amounted to an uncontrollable phobia. To get around this problem, she had Dad string open jugs of ammonia around the outside of the house and where we kids played.

And she taught us the conventional bear-country safety rules: make lots of noise, don’t run from a bear (a bear can run faster than you), don’t try to jump in the bay to escape it (a bear can swim faster than you), play dead if it attacks you, back slowly away and get home immediately if you smell a horrible stench, wear your bear bells, blow your bear whistle, climb thick trees with lots of limbs to impede a bear’s tree-hugging climbing abilities or its ability to push a smaller tree over…

She made bears sound like supervillains who we had no hope of escaping, with diabolical superpowers no mere human child could hope to defeat. This did not, by the way, improve the quality of my sleep.

Not content with the conventional, she got inventive. And, wisely or not, turned the stuff of our nightmares into playtime.

The bear drill, as she called it, appealed to our athleticism and our competitive instincts. That was how she framed it: “Let’s see how fast you can do the drill, from the moment I call ‘Bear!’ to the moment you’re all in the attic.”

Her plan was to get us all tucked into the cramped, dark attic of the one story floathouse if a bear ever roamed too close to the house or tried to break and enter. Though a brown bear, if it was determined enough and sniffed us out, could have torn the ceiling apart to get at us. I’m sure she thought that at least it would keep us kids from being underfoot and running loose in the event of a bear assault.

We never knew when Mom would instigate the drill. We’d be going about our business of building forts, attacking each other with bristly yellow skunk cabbage cones, swimming, rowing in the blue plastic rowboat that looked like one of the boys’ Fisher-Price toys, climbing trees, and generally living about as free and close to nature as kids could get without turning entirely feral.

When we heard, at any time of the day, “Bear!” we had to drop whatever we were doing, grab the hand of the nearest “baby,” and force ourselves to walk sedately to the floathouse before galloping up the ramp with its raised wooden stops and along the railed, narrow front deck to the front door.

On one typical bear drill we burst through the white-painted front door and Jamie jumped on the table and shoved the loosely fitted attic door (a square of plywood) to one side.

Megan grabbed Chris and tossed him to me and I handed him up to Jamie, who snatched him and threw him into the dark hole above his head. Robin came next, and he, too, was flung into the darkness. I pushed Megan onto the table and Jamie heaved her into the hole. Then he grabbed my hand and yanked me onto the table and shoved me in amongst my sweaty, giggling brothers and sister. Jamie athletically pulled himself into the attic and immediately slammed the door into place.

The five of us huddled together, panting in the hot and dusty darkness. We were supposed to wait as silently as possible, without moving, until Mom gave the all clear.

There was no light up there, and other than our breathing and the rustle of our attempts to get comfortable on the bare ceiling joists, it was quiet. It smelled dusty and mildewed with boxes full of magazines, paperback romances, eight-track cassettes, clothes from the Seventies, and other things that we couldn’t see but knew were there.

I imagined a camera with an outside view of the shining aluminum roof of the floathouse and the camera ascending, taking in the rectangular floathouse’s lengthwise perch on a small mud flat at the edge of the forest with a stream flowing out from under the house’s float logs down a gravel beach, past the old pilings down to the broad bay.

The view expanded to show the endless forest climbing ridges and mountains as far as the eye could see toward Canada. On the other side of the peninsula where the floathouse was, the remains of the cannery sprawled black and rusty in the tumbling, golden creek and on the rocky beach. Rising higher the camera took in the breadth of the bay that merged with Clarence Strait, an integral part of Alaska’s Inside Passage.

In all that space, there were no other humans. Just us.

But there were a lot of bears, some of them fishing in the salmon creek amidst the twisted cannery debris, on the other side of the peninsula from the floathouse. There were more bears than humans in this land.

Then I pictured the camera cutting back to the hot and dark attic.

“I think that was our fastest yet,” Jamie whispered.

I nodded, pushing at the hair stuck to my overheated cheeks and forehead. “I don’t think we can get any faster.”

“I wonder if Mommy was surprised?” Megan said.

“I wonder if she’ll give us a treat?” Robin speculated.

Chris responded, “I’m hungry,” and our bellies grumbled. We were always hungry.

The bears were hungry too, of course, but I never felt any sympathy for them. Not when my brothers and sister and I were potentially on their menu.

• • •

There were other things besides bears and spontaneous combustion to fear in our wilderness home.

We quickly found that the first storm we’d encountered at the cannery on our reconnaissance visit was not an uncommon event. Even inside our more protected harbor the wind could find us. And in the winter when the tides were high, blown up higher by a terrifying, roaring wind, a monster storm surge wreaked havoc on everything that floated.

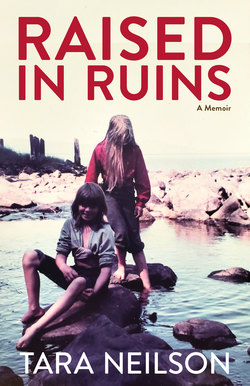

The floathouse in Union Bay. Opposite it is the wanigan with pilings on either side of the bay. The white spots are our skiffs.

Firewood logs broke loose, skiffs broke loose, the walkway to the wanigan broke loose, and one night during a hurricane-force storm, our floathouse broke loose.

It was a night when Dad was home. He was the one who knew instantly when the swifter cables holding our floathouse to shore snapped in the surge. He yelled for us all to get outside. Mom only stopped long enough to make sure we put on our lifejackets and then we scrambled out.

With only flashlights, we faced the black gale. Mom and the five of us kids, from oldest to youngest, were ordered to the back of the float where we had to grab hold of one of the broken cables to stop the floathouse from being sucked out into the larger bay. We planted our feet as best we could and our hands burned on the rusty, twisted steel strands that formed the cable. Our arms were almost yanked out of their sockets as the many tons of floathouse surged.

Dad jumped into our thirteen-foot Boston Whaler, puny looking against the sixty-foot length of the heavy float. He had all the force of the fifty-horsepower Mercury outboard at his command as he turned the throttle up and pushed against the house, trying to force it back far enough into position so that we could get a wrap of the cable around the brow log to hold it in place.

Wind whipped at our bodies, buffeting the little ones so hard it was a wonder they didn’t get blown away. Maybe only their grip on the cable kept them in place. A mix of rain and spray splattered us. The tree branches of the surrounding forest rose and fell in the gusts almost as violently as the floathouse rose and fell in the heavy, sucking surge.