Читать книгу Raised in Ruins - Tara Neilson - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER TWO

“WE’RE GETTIN’ OUTTA HERE!”

—Skip Robinson in the 1975 movie The Wilderness Family

WHEN MOM explained to Linda, Uncle Rand’s girlfriend, that she and Dad still planned to homestead the old cannery in the wilderness despite their friends dropping out, Linda tried to dissuade her.

“Romi, you have to have more faith in people,” Linda said. Maybe she was thinking that it was another instance of the rapidly-becoming-a-cliché story of a Vietnam vet alienated from humanity, dragging his family off into the wilds of Alaska.

But it wasn’t like that, not entirely, Mom thought.

They trekked the bare dirt trail that circled the village under mist-laden skies. The community trail’s narrowness only allowed people to walk single file under the towering canopy of evergreens, tendrils of overcast trailing into the treetops. The air was intoxicatingly fresh.

“You can’t just go off into the wilderness like this. People aren’t the enemy,” Linda assured her.

Weathered wood-frame houses hugged the hillsides above the winding path or perched beside it on barnacle-studded pilings over the beach. Every now and then boards corduroyed a boggy spot and Linda’s and Mom’s boots clomped onto them, the mud beneath slurping loudly. Sea gulls screeched from the small harbor that glinted hard and mirrorlike through the trees and crows answered them from deep in the moss-damped forest.

Mom kept to herself her “unworldly” reactions to the mystery and romance of the ruins. She’d long since decided that other adults, even the ones she connected with the most, never understood what she experienced. Places had personalities, they lived and breathed and either welcomed or scorned you. The ruins wanted her family.

Despite the fact that Linda had grown up in San Francisco while Mom had grown up on traplines, farms, and ranches in backroad regions, it was the city-girl Linda who was able to “do” the rural Alaskan lifestyle in a way Mom never could. Linda tackled trapping and flensing a skinned otter, steering Rand’s fishing boat, and everything else the men around her did with panache, while at the same time finding the time to crochet, sew, and design quirky, feminine crafts.

Mom wouldn’t know—and didn’t care to know—how to do what the men did, and though she wore a floppy, boiled-wool, faded-thimbleberry hat that looked like she’d knitted it herself, she’d bought it in a thrift store, allured by its wacky-cocky personality. The sewing arts were a deep, and deeply uninteresting, mystery to her and always had been.

She was not one of the millions of young people who, in the 1960s and ’70s, felt driven to spurn the materialistic world in the Back to the Land Movement. Despite her love of novelty and fashion and whatever was current on the modern scene, she, like Dad, were traditionalists and had no interest in the drug culture, free sex, or any of the other ideas of other people their age who dropped out and “went back to the land.”

According to Eleanor Agnew in her book Back from the Land, these back-to-the-landers thought that by going back to a simpler life and living close to and off the land, they could be better stewards of the world than the exploitative capitalist society that had given them the kind of privilege that allowed them to toss it all away on a fervent wave of idealism.

There were many of these free-floating idealistic types who latched onto Mom and Dad for their stability. My parents were young, but they were a married couple at a time when many young people derided the concept of marriage as being old fashioned and too restrictive.

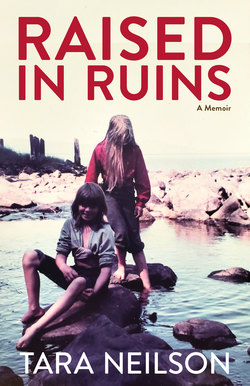

My dad and mom, happy that they’re moving to the ruins, leaving civilization behind.

Mom was a stay-at-home wife while Dad—despite his rebellious long hair and bushy beard (he was once mistaken by a Hell’s Angel member as one of their own)—always held down a steady job. They wound up, time and again, taking care of and providing bed and board for any number of youthful wanderers existing in a liberated, drug-induced daze with no thought of jobs, responsibility, or providing for themselves.

These drifters were the children of “The Greatest Generation” that had saved the world from the Great Depression and Nazism… which was a lot to live up to. Dropping out was easier than competing, not to mention nobler—if you could spin it that way. And if you could find a steady young couple, who were in sympathy with the idealism of the times but maintained a traditional way of life, to keep yourself safe and afloat, all the better.

There were plenty of those types in rural Alaskan communities, including Meyers Chuck—“hippies” who were drawn as much to the drug culture and liberation from age-old moral standards, as they were by the validation of living a simpler life. And, at that time, Alaska stood out as a state that welcomed eccentrics, non-traditionalists, and made the private use of marijuana legal.

Neither Mom nor Dad, even in their most antiestablishment moments, had been drawn to that culture. They didn’t even smoke cigarettes, though their parents and most of their peers considered it normal to do so. And when old-fashioned crafts became a fad that young and fashionable townspeople followed—sewing or crocheting one’s own dresses had a certain cache at the time—Mom, a sucker for almost any hip fad that came along, was immune to the appeal.

She supported individualism and nonconformity, but her idealism remained restricted to the mind and heart; she spurned all labor-intensive manifestations of the zeitgeist. It didn’t matter to her that this was not a particularly practical point of view for someone who was determined to live in the remotest heart of the wilderness.

“You should have seen how happy and free the kids were,” Mom improvised to Linda.

“The kids will do fine here in the village with other kids around them and a school to attend.” Linda was so certain in her opinion that Mom had a low-level sense of panic at the thought of being forced to give up the lonesome blackened pillars and rusting remains of the old cannery.

“You don’t know what it’s like having five kids in a place this small,” Mom said. “It’s like having a target painted on you. People are always complaining about every little thing they do, and I don’t want them to grow up being squelched all the time. I want them to be free, to do whatever they want to do, be whatever they want to be.”

As if on cue, a woman from the village steamed up the path toward them. Before she reached them, glimpsing Mom’s floppy hat behind Linda, she barked, “Do you know what your kids are doing down at the dock?”

Mom didn’t get a chance to reply.

“They found a whiskey bottle on one of the boats, filled it with water, and are pretending to drink booze!” The woman huffed.

Linda turned and looked at Mom and acknowledged, “I see what you mean.”

There were no more arguments after that. Her floathouse home, Southeast Alaska’s version of the covered wagon of Oregon Trail fame, would be towed to the ruins.

• • •

When loggers arrived in Alaska and first eyed the timber-rich wilderness of the last great temperate rainforest on the planet, they were stymied by the multitude of waterways that prevented logs and people from being transported by land. They adapted by moving everything onto the water on rafts.

Logging machinery, power plants, stores, schools, and entire towns were built on rafts made of enormous logs lashed together. The floating towns and machinery were towed from one place to the next by powerful, sturdy tugboats that inched along the Inside Passage. (Later, when the logging boom ended, all these floating communities and single floathouses were moored in place and rarely ventured out onto the unprotected passages.)

When we moved to Cannery Creek, it wasn’t the first time our single-story, wood-frame house on a raft of giant logs had been towed abroad. It had been towed from Prince of Wales Island to the Ketchikan area and then to Meyers Chuck where we got it. In our keeping it had been towed twice across Clarence Strait, one of Alaska’s most unpredictable and dangerous inside waterways.

The first time had been so that Dad would have his family near his logging job, his home anchored in a small bight along the winding passage that leads to Thorne Bay, the largest logging camp in the world at the time. The second time it had been towed back to the fishing village of Meyers Chuck, where Mom’s parents and brothers lived. Now it would be towed to the old cannery site while Dad would continue to work at Thorne Bay as a scaler and bucker. The plan was for him to commute home on the weekends across Clarence Strait in the tiny skiff.

Dad had no interest in whatever seasoned arguments there might have been about the crossing being “impossible” at certain times of the year, or hearing that his family couldn’t be left without provisions or a man’s protection for weeks at a time.

I think there was some relief in not having his family around, demanding things of him he couldn’t give. Being a husband, being a father—especially being a father—were skills he didn’t possess. His own father, a World War II veteran, had been so harsh toward him that his mother had arranged for her mother to raise him while his siblings stayed at home.

The one time his father had been proud of Dad was when he signed up for the Army. His father wrote him a letter every week, though he wasn’t normally a letter writer. Yet, when Dad came back from Vietnam with a beard, his family disowned him. At a time when the mainstream was reviling the war and its veterans, the next letter his father wrote him was “anonymous” (although still in his handwriting), suggesting that it might be better if there was no Vietnam vet in the family.

What did Dad know about being a good father, or any kind of father at all?

He could have asked the old-timers for their advice about his plans for leaving his family in the bush while he worked across the strait, but he didn’t. He probably wouldn’t have gotten much.

When they first arrived at Meyers Chuck, he and Mom attended a community “town hall” meeting where they realized from the awkward silence that fell at their arrival that they and their five kids had been under discussion. They were invited to participate, but when they spoke up they were seen as overopinionated newcomers.

Besides, even if the locals had taken Dad under their wings, the old-timers’ ever-so-reasonable and knowledgeable arguments wouldn’t have impressed him. He’d long been accustomed to thinking that, as he liked to joke-but-not-joke, “Where there’s a Gary there’s a way.” No matter how impossible something seemed to be, he could find a way to make it work.

Surviving a war with a Purple Heart Medal, which he refused to accept, had solidified his certainty in his ability to carry out what he’d decided on. He didn’t balk at the dangers or the brutal load of hard labor that would be required; holding down a physically demanding job all week and homesteading the wilderness on the weekends suited him just fine.

• • •

Although we kids didn’t know it at the time, we almost didn’t get to live at the old burned cannery because the other families got cold feet and dropped out.

Fortunately, the company that now owned the cannery, US Steel, was willing to let my parents take over the entire lease with payment due on a yearly basis. It would be easy enough to keep up with since Dad’s logging job was a well-paying one for the times.

The woman who had originated the plan, the village school teacher, felt so guilty at leaving my parents high and dry that she arranged for friends of hers, Muriel and Maurice Hoff, who had their own cabin cruiser called the Lindy Lou, to go with us.

The Hoffs were typical back-to-the-landers who’d come from the realm of academia to live a simplified, rustic life on a boat in the Alaskan wilderness. Muriel would stand in as a teacher since Mom knew she wasn’t up to coping with our education needs.

The Hoffs’ boat would come in handy when it came time to move the floathouse. Two of Mom’s brothers, Uncle Rand and Uncle Rory, also volunteered their commercial fishing boats to help us make the move.

The moment it really struck me that we were leaving all of civilization behind for the foreseeable future was when I had to return the books I’d borrowed from the village “library,” a bottom shelf in the tiny, one-room general store.

I squatted down, pushing the old clothbound books into place, and my eye was snagged by two more books that I longed to read: a Roy Rogers Western and a book about a horse and a dog going on a forest adventure. I couldn’t borrow them, Mom explained, because there was no telling when I’d be able to return them—if ever.

That made it starkly real. I emerged from the store into the late afternoon light and stared around in awe at my last glimpse of people and houses, hearing the private generators rumble and the bells on the fishing boats’ trolling poles ring out. The red strobe light on top of the telephone tower that serviced a single community phone mounted to a tree, a light that used to lull me to sleep at night, was beaming out a hi-tech message of goodbye.

• • •

We left at the break of day, before it was full light, to catch the tide.

The Velvet towing our floathouse and wanigan out of Meyers Chuck to the cannery. My dad is in his 13-foot Boston Whaler watching to make sure everything works. The Wood Duck and Lindy Lou (out of sight) push from behind.

Not that any of us kids were awake when it happened. We were snuggled up in our bunks while the adults moved quietly around the damp decks outside, the dripping forest muffling most sounds.

They coiled up the huge, heavy mooring hawsers that had held our home to the trees and then ran a towline out to the Velvet, Uncle Rory’s and Aunt Marion’s commercial fishing boat. (It was a black-hulled boat with a white cabin and orange-red trim. When the Velvet was decked out in longline buoys in circus balloon hues—orange, pink and blue, and yellow—it was a sight to behold on Southeast Alaska’s remote fishing grounds.) Uncle Rand in his own fishing boat, the classy little Wood Duck, and the Hoffs in their cabin cruiser Lindy Lou settled in to push the floathouse from behind.

The photos show that it was a crisp fall day, overcast with smoke from our floathouse chimney wafting behind us as our home was towed out of the long shadows of the tidal lagoon known as the Back Chuck (situated behind the Front Chuck, Meyers Chuck’s harbor).

The floathouse was then about twenty-five years old and used to belong to Mom’s parents, but Mom and Dad bought it from them when we first moved to Alaska three years before. It was a one-story, regular wood-frame house built in a “shotgun” trailer-house style. Half of the house was a large communal bedroom for us kids, plus the bathroom. The front half had my parents’ tiny bedroom, and beyond it was the combined kitchen and living room.

The house was sixteen feet wide and forty feet long, with forest-green ship-lapped siding and white trim around the windows, including the huge bay window that had a bullet hole high up in one corner.

Tied alongside our floathouse was a much smaller, ten-byfourteen-foot one-room floating cabin called “the wanigan” that my grandfather had built four years before, which Mom had since bought from him. It would serve as our schoolhouse.

The floathouses crept along, testing the lines and what kind of strain the Velvet’s engine could take, before they settled on a steady two-knot pace. The adults calculated it would take three to four hours to tow the floathouse to the cannery site.

When we woke up, the floathouse was already underway. The five of us kids and Moby excitedly ran around the house and—when Mom wasn’t looking—made a daring run outside to leap across the churning water between the floathouse and the wanigan. Mom had warned us against this feat, telling us horror stories of how a child could get trapped between the two moving buildings and be mangled for life, sawed in half, and/or drowned. As usual, her horror stories encouraged us to test our mettle.

We stood there, listening to the engines of all three boats rumble, hearing the constant splash of the water against and over the logs the buildings sat on, and watched the wanigan tug on its lines like it wanted to escape the solid maturity of the big floathouse.

Jamie, as the ringleader, was on lookout duty to make sure none of the adults were watching. When the coast was clear he’d whisper: “Now!” and one of us would take the exhilarating and frightening jump across the turbulent water to the wanigan.

When the babies insisted on their turn, Megan and I each took a hand of a little brother and jumped them across, hushing them—and our own giggles—when they shrieked with glee. Moby ran along the floathouse deck with his tongue hanging out, his eyes bright and laughing at the death-defying sport.

We were in our lifejackets, of course. We lived in our lifejackets. The one rule Mom was successful in establishing right from the beginning was that no child was to step out of the house without their lifejacket on. It was comforting being encased in protective gear—like a suit of armor against the Alaskan bush’s many dangers. At times we even slept in our lifejackets.

The water was millpond smooth, though all the adults knew that the weather in this particular part of Clarence Strait was subject to change without notice every moment. It would have taken weeks of planning, listening to weather forecasts, checking the tides, calculating how long it would take to travel to the cannery site; and then the frustration of having to reschedule the trip when an unforecasted storm raged through.

It would have been a tense time for the adults before and during the tow, looking out for any sign that the weather was about to kick up. These were dangerous waters we were traveling in—shipwrecks on the shores we passed gave silent testimony to that.

Back inside the floathouse, Mom gave us a quick breakfast. We ate while watching the storied Inside Passage glide past our windows with Christopher Cross’s “Sailing” playing in the background. Dad was in continual contact with Rory on the Velvet, Rand in the Wood Duck, and Muriel on the Lindy Lou by Citizen Band (CB) radio.

By a freak of bouncing radio signals, truckers from California would break through the squelch with their: “10-4, what’s your twenty?” and “Copy that. You’re coming in wall to wall and treetop tall.” An entire array of twangy CB slang periodically burst through the speaker. The rowdy rap of truckers hauling freight along America’s West Coast highways beamed into our wilderness home all the years we lived at the cannery.

The little inlet we headed for was a hidden harbor—it couldn’t be seen from a direct approach on the cannery. It was sheltered from the northerly gales, though southeasterly storm surges were free to wreak havoc in there, as we soon discovered.

The harbor was shallow and went dry on minus tides. In addition, there were submerged dangers everywhere, entire forests of pilings (studded with steel spikes that had held long since rotted or scavenged beams in place) that had at one time been the foundations for pre-WWII boat grids and haul-outs.

This harbor was where the superintendent had lived and where the cannery had repaired and stored their fish barges in the off season all the years it was in operation.

The cannery encompassed twenty-one acres of wilderness and had two sides: the “superintendent’s inlet” where our floathouse was parked, and “the Other Side,” the creek side where the cannery itself had been. They were separated by a high, stubby peninsula.

In the superintendent’s inlet the orderly sentinel pilings, silent witnesses to the passing years, stood in marked contrast to the twisted, scorched chaos we’d found on “the Other Side.” There had also been a building that had overlooked the superintendent’s inlet that was later put on a float and towed the seven miles to Meyers Chuck. There it was put back on land where it still stands today, painted in cannery red, and known locally as “Hotel California” for the hippie inhabitants who lived there in the Seventies.

The Velvet, Wood Duck, and Lindy Lou couldn’t maneuver inside the shallow harbor with all the underwater hazards, so they untied from the floathouse and Dad used his skiff to push the house to a central location, tying it to trees on shore and a tall piling on the wanigan side. After it was secured in position, the Lindy Lou picked its way inside and tied up to the floathouse on the other side from the wanigan.

There’s nothing quite like being in your familiar home and glancing out the window to see not the view you’ve lived with for years but terra incognito—an unknown, unexplored landscape.

The light shines through the windows differently, making the inside of the house seem subtly strange. There’s a continuing, pleasurable, tingling disorientation about it, a breathtaking, awe-inspiring sense of waiting discovery—an almost Alice in Wonderland sense of having fallen down the rabbit hole with all kinds of amazing experiences to live outside the familiar walls of your transported home.

Once the house sat down on dry land, the water gradually receding and lowering us onto the ground as if our house was on a giant elevator, Mom couldn’t hold us kids back. She yelled at us to stay within sight of the house as we ran outside. The tall forest of evergreen trees encircled the small harbor, with drift logs, beach grass, and seaweed in a jumble at their heavy skirts.

I don’t know about my brothers and sister, but I felt like a Star Trek adventurer who had landed on an unknown planet with the remnants of a long-ago civilization to explore. On this side the ruins, although less extensive, were better preserved. All the buildings and barges and anything still valuable had been moved out, so what remained were foundations, wire-wrapped wooden waterlines, and an old winch for hauling out the cannery barges.

We found signs of ancient Native occupation in the form of a “fire tree.” The tree was a huge silo of a cedar tree burned hollow in the center. It was outside the part of the cannery that had burned in 1947, and it wasn’t a lightning-struck tree since the only burned section was the interior. It was so huge that I could walk around inside and stand in the middle without being able to touch the sides. I used to wonder at the mystery of it, why it had been deliberately burned hollow inside. Later I read that modern researchers hypothesize that the Tlingit tribe used such trees as a way to preserve their precious communal store of fire from the persistently rainy climate.

Our greatest, most awestruck discovery was a grave. It was marked by a weathered and rotting wooden cross on the point that overlooked the bay. (Later we found another one farther back in the woods.)

Who was buried here? What had been their stories? There was no one to ask so we were free to imagine our own stories. There was plenty of scope for a child’s imagination in the ruins that we now called home.