Читать книгу From Melon Fields to Moon Rocks - Dianna Borsi O'Brien - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 7

The Inspector

Charles didn’t know it at the time, but the summer of 1941 would be the last time he’d work as a farmhand.

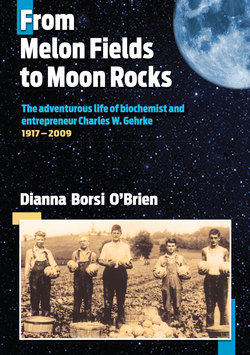

Although he had two Bachelor’s Degrees and a Master’s Degree, jobs were scarce. While Charles was looking for a job, he continued to work as a field hand. Ruth Jarvis remembered Charles stopping off in Zanesville to visit Virginia with a load of melons.

Finally, a job offer in Canton, Ohio, came along, and Charles left manual labor behind for good. Dr. Scott, DVM, offered Charles a job as a food inspector of the Canton Health Department with a yearly salary of $1,800. He asked Charles, “Is that enough?” To Charles, that looked like a lot of money, so he took it. “I soon learned $1,800 didn’t go very far,” Charles said with a laugh.

A gritty city in the 1940s, Canton boasted plenty of steel mills and factories, many of which have closed since then. Near Akron, Ohio, Canton was a bustling, growing city. On many days, Charles said, the city was enveloped in a deep, impenetrable smog, limiting visibility to a few yards.

His job came complete with a police badge and involved inspecting restaurants, beer gardens, groceries, bakeries, pie shops, and food-processing plants. Charles liked Dr. Scott, who let him do things on his own, which suited Charles’s independent nature. He didn’t like riding street cars or buses to get to all the places he had to visit. As for the job itself, Charles said, “It was interesting, but I didn’t like it very much.”

As usual, Charles found a mentor. Richard Dishnica, a Greek man with a bad leg who was head of the Eastern Ohio Restaurant Association, took Charles under his wing and made sure he was included in the local weekly poker game. Restaurant owners paid attention to Charles when it came to complying with city health codes.

Once again, for lodgings, Charles found a bargain, taking care of a house owned by a woman who lived out of town. The house was located on Cleveland Avenue, the main highway to Cleveland, and the road roared with the traffic of the output of Canton’s factories: hundreds of half-tracks, military vehicles with tank-like treads at the rear, all on their way to Cleveland for overseas duty.

Charles’s brother Hank also moved to Canton at the time, having taken a well-paying job as a crane operator. Charles often borrowed Hank’s “Terraplane” truck, a vehicle he fondly recalled, to visit Virginia in Zanesville. When he couldn’t use Hank’s truck, Charles took the Greyhound or the Ohio Transit bus to see her.

Back home, things were moving along for his family, too.

Louise finally had moved her family, with three children still at home, to a house on Third Street in Coshocton. At last the family had electricity and running water—and a source of income that didn’t involve hard labor. The family’s new home was large, which allowed Louise to rent out rooms in the house. The move to Coshocton also shortened Louise’s walk to her job at the glove factory in Coshocton and Charles’s siblings’ walk to school. Instead of facing a three-mile walk to school, Lil (sixteen), Evie (fourteen), and Ed (twelve) had to walk only a few blocks to Coshocton High School.

The move was a good one for the family. In addition to being closer to work, Louise liked being able to walk to all the stores. Lil recalled this time fondly, even how she and her sister Evelyn had to help their mother learn to pronounce the name of their street correctly. With their mother’s thick German accent, the name of the street often came out sounding like “Turd Street” instead of Third Street.

In Canton, Charles’s work had its surprising and sometimes unpleasant moments. As Canton’s health inspector, Charles had a circuit of inspections to complete. But sometimes the Canton Health Department received a complaint, and he’d have to make a special inspection. He’d been called to inspect a place involved in slaughtering and selling chickens, something typical in the 1940s. The building had a dirt floor, and as he went in that night, he shined his flashlight around the room and saw hundreds of rats running everywhere. The sight jolted him with memories of killing rats during his high school days of pest eradication with Mr. Hoover.

While he liked being, as Charles put it, “The Inspector,” with its accompanying police badge, and liked learning more about bacteriology from a fellow OSU grad who ran the lab at the Health Department, Charles longed for a more professional job, something more in line with his education, including his Master’s Degree in Biochemistry.

Charles told himself, “I’m going to try to get out of this.”

So Charles began applying for positions at small colleges.

Down the Aisle

Charles’s trips to Zanesville were paying off, and on Christmas Day 1941, Charles made Virginia his bride. It was a small affair. The ceremony was held at her mother’s home with Virginia’s childhood friend Ruth Jarvis and a few others in attendance. Ruth recalled Virginia walking down the staircase instead of a church aisle. The wedding announcement noted that she wore a white, floor-length dress with a full skirt and only a single strand of pearls for jewelry.

Charles can’t remember why they picked Christmas Day as a wedding date, only that it was a convenient date everyone had open on their calendars. He does recall they spent the wedding night in a motel near Buckeye Lake in Columbus.

After sixty-five years, the only regret Charles could remember about their Christmas nuptials was Virginia wishing they had photographs of their wedding. It would be sixty-five years later that Virginia would pass away, on Christmas Day 2006, their sixty-fifth wedding anniversary.