Читать книгу From Melon Fields to Moon Rocks - Dianna Borsi O'Brien - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 4 Coshocton High School

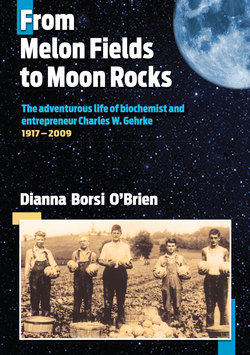

ОглавлениеIn 1931, Charles began to walk the same three miles to Coshocton that his mother walked to work, but he did it to attend Coshocton High School. With Hank dropping out of school and Charles going on to high school, Charles was beginning to move out of his brother’s shadow.

As Charles put it, “He always called the shots.” However, Charles saw his brother Hank as a major guiding force, always ready with encouragement.

The move to Coshocton High School provided Charles with new champions for his welfare, one of whom would help guide him away from Coshocton and well beyond central Ohio. At Coshocton High School, Chemistry teacher Richard McKissick always made it a point to urge qualified students to go to college. Naturally, Charles caught his eye.

At the same time, Charles signed up for Future Farmers of America (FFA). The FFA teacher Delmar Hoover also took an interest in Charles. He got students involved in an afterschool competitive project he called “pest eradication.” The project involved putting the students into teams of five or six students each and then taking them from barn to barn, farm to farm, to see who could capture and kill the most rats and sparrows.

Charles remembered shining a flashlight into the hay mows so the birds would fly toward the light and the students could catch them and pull off their heads—proof of their successful efforts. Charles and his friends in Canal Lewisville expanded on the supervised pest eradication trips by going out on their own from time to time, bringing rat tails and sparrow heads to school.

Hoover also taught public speaking, which helped transform Charles from a shy, reticent farm boy into someone comfortable talking to anyone. He won the regional public-speaking contest and even competed at the state level, coming in fourth at the competition in Columbus, Ohio.

Charles’s teachers weren’t content with simply guiding Charles’s high-school efforts. They wanted to guide his future as well, pushing him toward attending Ohio State University after he graduated. But s mother wasn’t for the plan. She wanted her son to stay home, get a job, and help support the family.

To try to persuade her to send Charles to college, the two men visited Charles’s mother at home to talk to her, but she wasn’t swayed. She asked them where she was going to get the money to send her second son to college.

At the time, Hank was working at Clow Pipe Company, which helped, but in 1935, as Charles’s graduation approached, she still had Ed (six), Evie (eight), and Lil (ten) to consider. She needed Charles’s financial help.

Even Charles had mixed feelings. He wanted to help his family, but he also knew making a living farming, especially farming the land they had, wouldn’t be easy. “We didn’t have a farm worth anything,” Charles said. “Thirteen acres of nothing. Thirteen acres was a lot at the time, but there were only four or five acres that were fertile.”

Hank helped, though. A 1995 Coshocton Tribune newspaper article reported that Hank insisted Charles go to college. “I knew what work was, and I wanted them to have things a little better,” the article quotes Hank as saying.

Later, at Hank’s memorial in 1999, Charles acknowledged his brother’s help—and the divergence of their lives. “In 1935, with encouragement from my high school teachers and Hank’s help, I enrolled at OSU. Thus our ways began to take separate paths, but always we kept in contact.”

That kind of loyalty would become a hallmark of Charles’s life.