Читать книгу From Melon Fields to Moon Rocks - Dianna Borsi O'Brien - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 3

Taking Care of Each Other

The Gehrkes loved retelling their family’s solution to childcare: Charles and Hank taking baby Ed with them when they worked in the melon fields or the cornfields. In another makeshift childcare solution, their mother arranged for Charles and Hank to take four-year-old Lil to school with them at the grammar school two blocks from their home while Louise cleaned houses. Lil was too young for school, so the teacher simply let Lil color or draw. Lil, however, recalled this differently and attributed her teacher’s lack of attention as antipathy toward the Gehrkes because they were German.

Some family members said that from time to time they thought financial problems might lead to sending Ed, Lil, or Evie to live with a neighbor or another family member, but Hank and Charles wouldn’t hear of it. Instead, the two boys kept busy working as field hands for area farmers, earning money to keep the family together.

At age ninety, Charles could still rattle off the names of the various weeds he attacked with a hoe and recount how he would watch the farmhouse in anticipation of the white flag that signaled the lunch break. He and Hank worked the fields together, earning ten cents an hour each for hoeing acres of corn. They worked from sunup until five or six in the evening, keeping their hoes sharp with a file, while Ed toddled after them.

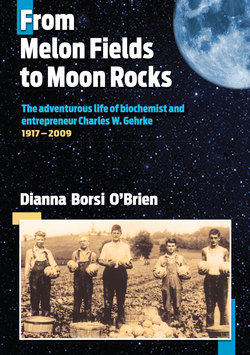

The two also worked in a cantaloupe and watermelon operation of several acres that united four different families. The Blairs owned the land, while the Hebling family owned the greenhouse in which they grew the potted plants for the fields. Another family, the Baughmans, also operated greenhouses, where they grew seedlings for several weeks after germination before replanting them in the fields. They also provided the fertilizer, pesticide sprayers, and trucks.

“We were the labor,” said Charles. The Gehrkes transplanted the melon plants, sowed the seeds, weeded by hand, harvested the melons in July and August and then loaded the produce into trucks parked at one end of the field.

For two or three years, the Gehrke boys made four to five hundred dollars as their share, a tremendous amount of money in the 1930s. To protect their crop from thieves, Charles and Hank would sleep in a tent in the fields during the summer, and for a while things were good in the melon fields.

“Melon truckers came from Cleveland, Pittsburgh, and Columbus to take two to five hundred bushels of cantaloupes per day for several weeks, at fifty cents a bushel,” wrote Charles, describing those days working with Hank.

But then one summer, no trucks came to pick up the melons. The Depression was on. They ended up feeding five hundred bushels of melons to the hogs.

The two made other entrepreneurial efforts. In 1934, Hank and Charles decided to grow potatoes at the Raymond Geib farm, near a farm Hank would later buy. “We had a great crop of Ohio russets,” related Charles, describing the experience during his talk at Hank’s memorial service. “This was the depths of the Depression, and one day the Eastern Ohio Farm Market called to say they would like to buy two-hundred one-hundred-pound sacks at one dollar per sack.” The two boys rented a truck for twenty dollars, loaded it with potatoes and headed to Columbus, seventy-seven miles from Coshocton, for what seemed like a great economic deal. But when they pulled up, the manager came out and said, “Boys, the price of potatoes today is ninety cents a sack.” That, said Charles with a laugh, was his first economic lesson: Get it in writing.

Between their agricultural ventures—and misadventures—the two worked as farmhands during the summer as well as during the school year. Charles recalled sitting in the field in January shucking corn, using a special glove with a metal hook to pull the husks off the ears of corn. The corn husks and stalks would then be given to the boys for their labor and piled into a wagon to be taken to their home to be fed to their cows. The ears of corn would go to the farmer for his hogs.

Midsummer, the boys worked shocking wheat, tying the wheat stalks into sheaves. These bundles of wheat were stacked in a circle and topped with several sheaves, with the wheat stalks bent outward to allow the water to funnel off. Roughly four to six weeks later, a threshing machine would be brought to the field, and Hank, Charles, and other area farmhands would put the wheat straw through a machine, which baled it into big squares. This was one of the few jobs Charles truly disliked, not because it was hard work but because of the dust, which choked him, and the wheat mites, which caused him to itch, an affliction he said could be solved only by taking a dip in the nearby river.

Hated Task

Along with working as farmhands, Charles and his brother Hank helped their mother operate a truck farm, growing beans, peas, asparagus, radishes, raspberries, cabbage, spinach, and rhubarb on their family’s thirteen acres.

Charles didn’t complain about planting, weeding, or any other hard labor, but he often talked about the one task he longed to escape: peddling the produce door to door in Coshocton. Selling the produce required Charles and Hank to load up a Model T with vegetables and fruits and head to nearby Coshocton to try to sell it door to door, sometimes going to well-to-do homes. “I felt out of place,” he said. Charles felt like he was asking for some kind of a favor, although he wasn’t.

Charles often talked about the time they came home at the end of the day with only ten cents after trying to sell radishes at five cents a bunch, and five cents of that had to go for gasoline for the car. Other days, however, the effort was worth it, and the boys would earn twenty to thirty dollars a day, a substantial amount in the late 1920s and early 1930s. All the money went to their mother, making things just a little easier for the family.

While the family laughs today about the ups and downs of the truck-farming business, the garden provided a lot of food to be stored in the cellar for winter, including potatoes, turnips, cabbage, and apples, as well as countless jars of canned sauerkraut, vegetables, and fruits.

No Bad Memories

Driving through the area in 2007, Ed, Lil, and Charles laughed at the memories of growing up in Canal Lewisville. Ed stopped the car to point out the bridge where he and other local boys had played a game that involved throwing rocks at each other, until one of them ended up with a gash on his head.

Standing in the yard where their home once stood, Lil recalled running down the alley to the schoolhouse a few blocks away, and the school teacher watching from the window, counting Lil on time for school if she managed to get even her toe on the school grounds before the bell rang.

The children attended a two-story schoolhouse in Canal Lewisville for grammar school. Grades one to four were on the first floor, with grades five to eight on the second floor. It was at school that Charles learned English; at home, his family spoke only German. Charles kept his ability to read and speak German throughout his life.

It was also at this school that Charles’s brother Hank finished his education, dropping out after the eighth grade to take a job with Clow Pipe Company to help support the family. Family tales say Charles wanted to follow suit, but Hank wouldn’t hear of it, telling him, “You are smart, and you’re going to get out of here.”