Читать книгу From Melon Fields to Moon Rocks - Dianna Borsi O'Brien - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 13

Creating a Team

For Charles, the first step toward streamlining the laboratory processes and aiding his fellow researchers required assembling an energetic, driven team to help him get the job done.

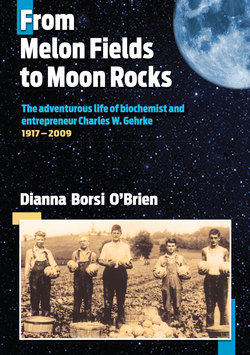

Charles brought to MU the lessons he’d learned as a farmhand in Canal Lewisville and as a one-man Chemistry Department at Missouri Valley College. He knew a big job required a team of people. In the melon fields, he and his brother were the labor. In Marshall, he’d recruited bright students to assist him. Now, at the University of Missouri, Charles would be the leader, and he made sure he recruited a team worthy of his goals.

So he turned his attention to a labor pool he knew well: the small colleges in Missouri, including Missouri Valley College, Southeast Missouri College, Drury College, William Jewell College, and Central College. He knew the schools drew talented students, and he knew he and MU could offer them more than the smaller colleges could.

For starters, he offered students something they couldn’t always find elsewhere: a living wage. At the Experiment Station, starting in the 1950s, Charles gave students the opportunity to earn as much as four thousand dollars a year working full time as chemists while attending the university part time, six credit hours a semester. Students could also work part time and attend school full time, carrying nine to twelve hours each semester and earning $100 to $120 a month.

Jim Ussary joined the staff at the Experiment Station in 1961. He’d first met Charles in 1958 when he took a class from him as an undergraduate. He said the wages enabled him to return to school and support his family. While working full-time nights and weekends at the laboratory, Ussary was able to earn a Bachelor’s Degree in 1960 and a Master’s Degree in 1964. He went on to help Charles found Analytical Biochemistry Laboratories (ABC Labs) in 1968 and to become its first president.

The employment opportunities Charles offered would draw twenty to thirty graduate students from small colleges across Missouri to work as chemists in the Experiment Station Chemical Laboratories while they pursued advanced degrees. Many students in the sciences at MU also worked part time in the laboratories on an hourly basis.

While the program helped students, it sometimes drew the ire of other MU professors because the wages Charles paid often topped those offered by other departments. But the criticism didn’t bother Charles. Charles had grown up with little parental supervision, somewhat ostracized due to his German background and his fractured family, and he’d learned to do what he thought was right. He wasn’t about to start worrying about what others said.

Charles wanted to help students in some of the same ways he’d been helped. He knew how difficult it was to make ends meet while attending college. He also recalled how much it helped him to live inexpensively at Ohio State University’s Stadium Scholarship Dorms. He just wanted to give students a leg up.

The students were more than labor. They brought a drive and excitement to the laboratory, and their graduate work often contributed to Charles’s mission of improving the methods used at the lab. Ussary, for example, focused on finding new and improved methods of testing for potassium for his Master’s Degree.

A Heady Brew

Charles never had just one or two students; he typically had roughly a dozen students and nearly twenty staff members on hand. During the 1960s, his staff would include six chemists from Japan, each one spending a year in Charles’s laboratory while working on a Master’s Degree in Chemistry. After a year studying with Charles, the students would return to Japan and their employer.

Through the years, Charles worked with students from countries including India, China, Norway, Vietnam, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh. His students also included those doing postdoctoral studies from France, Germany, Austria, Poland, Finland, Ukraine, Russia, and the Philippines. Years later, he and Virginia would visit many of his former students in their home countries, where they were working as scientists—something Charles took great pride in.

By the time Charles retired from the university in 1987, he had supervised and guided more than sixty students in obtaining their Master’s Degrees or doctorates and had served on many graduate committees.

His large number of students created a fertile ground for developing new ideas, new approaches, and, as Charles constantly urged, new solutions.

Ussary recalled a time when he was eating lunch with one of his fellow graduate students, Don Roach, and the two were discussing a problem Roach faced analyzing for a particular amino acid. Off the cuff, Ussary made a suggestion, and Roach jumped up and went back to the lab immediately to try out the new approach. “He didn’t even finish his lunch,” said Ussary, laughing at the memory.

Charles had his team of workers.

Key to Success

“I always had a team,” said Charles, “a staff of twenty and fifteen to sixteen graduate students. I worked with them, listened. Sometimes we modified their ideas, tried their ideas. Many times, I learned from them and picked up new approaches.”

David Stalling echoed that sentiment. Recruited from Missouri Valley College in 1952, Stalling received his master’s of science degree and his doctorate under Charles’s direction and joined the Experiment Station staff in 1962. Yet, he said, “I never felt a downward tilt in the relationship. He would later work with Charles to pioneer the techniques used in the analysis of the lunar samples and would found ABC Labs in 1968 with Charles and Ussary.

Charles fostered a sense of give-and-take in discussions between students and professors. Stalling said one interchange led directly to a patent he and Charles developed, which is still in use today.