Читать книгу From Melon Fields to Moon Rocks - Dianna Borsi O'Brien - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction

ОглавлениеHow did this book come about?

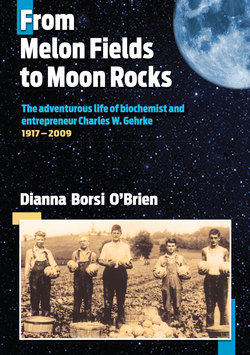

The first time I heard about Charles W. Gehrke was when his son Jon Gehrke called me. He said he and his sister Susan Gehrke Isaacson were looking for a writer to work with his father to write a book about his life. His father, he said, had been planning on writing a book about his life for years, but now it was time to get started. They’d just buried their mother, Charles’s wife, who had died on their sixty-fifth wedding anniversary. They even had a title for the book, he said, “From the Melon Fields to the Moon.”

The fact that they cared enough to make this kind of call seemed interesting, so I asked him a question any crusty journalist like myself would ask, what made him think his father deserved a book about his life?

Well, Jon explained, his father had come from a tough background, very poor, but had gone on to found a successful company, ABC Labs. Perhaps it’s that I’m a journalist and I’m used to hearing stories like that, of people coming from tough times and going on to success. Or perhaps it’s because I’m a long-time resident of Columbia, Missouri, home to a major university and two colleges, and I’ve grown accustomed to hearing about people who have done amazing things like founding their own successful companies. Even Jon’s mention of his father’s NASA work wasn’t surprising, by this time NASA spaceflights felt commonplace. Then it dawned on me, it was his son calling, and I thought about how many famous people had troubled families, estranged children or worse, situations where the children never would have made a call asking a writer to take on the project.

Then I began to listen.

It also dawned on me what he’d told me already, his father had just buried his wife of sixty-five years. That’s when it hit me: Here’s a surprising story, a story of a family man, who loved his wife, and had children willing to find a writer to work with him. And he’d founded a major company that was still going strong.

Still I had reservations. I didn’t want to work with someone who was writing a book just to make his children happy. I told Jon I’d be willing to meet with his dad—if he called me himself. I didn’t want to work on a project with a reluctant participant.

After doing a little research on Charles W. Gehrke and ABC Labs, I put the project out of mind, thinking Charles would either call or he wouldn’t. What I’d learned was impressive, but I didn’t want to prod someone into writing a book he didn’t want to write. I wanted to work with someone as devoted to a project as I’d be.

Little did I know that I’d met my match.

Charles finally called and asked me if I wanted to meet him at a nearby restaurant. I arrived a little nervous. I wasn’t sure if he’d accept my going rates or whether he’d be the kind of person I wanted to work with. If I was going to spend some time on this project, I wanted to work for someone I could work with—not someone I’d always be working for. Nor was I willing to write a book with just the facts the subject wanted people to know and not the whole story.

Charles was a delight at that lunch and at every other meeting we had in the two years we worked together—he was also always completely himself.

At that lunch and always, he was a gentleman, pulling out my chair for me. He was indeed a boaster, but then his accomplishments had given him something to boast about. He described how he’d founded ABC Labs. Later I’d learn he founded it with the help of several partners, including one that few people knew even existed. I know because later Charles talked about how he started the company with two of his colleagues, and I learned about an early fourth partner because I read through documents and letters from the early days of ABC Labs.

During that first meeting, he revealed a character flaw I’d later find out about in spades—the desire to drive the car even when he wasn’t in the driver’s seat. He told me he’d been out to look at the new construction going on at ABC Labs and how he wanted to make sure they didn’t make any mistakes in building the laboratory. No matter that at this time he wasn’t even on the board anymore, he just still wanted to offer a few pointers to those in charge.

At our first meeting, I asked Charles my most important question, the one that determined whether I’d take on the project or not: “Do you want me to write this the way it really happened or do you want me to write it the way you want it to look?” His answer? “Write it the way it happened.”

Factual matters

So I did. Our mutual commitment to the truth didn’t mean he always liked it, but no matter what I wrote, what I learned and reported back to him, he never once corrected a factual matter, edited out a negative finding, or balked at the truth I learned during the more than three dozen interviews I conducted and the countless documents I reviewed.

After our first lunch, the next time we met was at his home, at his desk (two card tables pushed together). He was ready with a check, an outline, and a list of names of people for me to call. Over the next two years, we’d meet every week, and he’d tell me more about his journey from the melon fields in the foothills of the Appalachians, to founding ABC Labs and his last years as a practicing biochemist searching for the answer to cancer activity in blood, serum, and urine. He also tried to teach me about electrons, molecules, the make-up of sugar and gas-liquid chromatography.

In our meetings, he’d rattle off names and telephone numbers from memory of people I should contact. During those years, I interviewed dozens of people from his past, and I uncovered things that surprised both of us. When I uncovered audio recordings of a radio show that revealed him predicting they’d find life on the Moon, we were both surprised. He and history had forgotten how unusual and precarious the first Moon missions were for both those involved and for those back on earth. At the time of the Moon missions, many had feared that they’d bring back some kind of terrible, sinister pathogen that would wipe out life on Earth, but time and history had erased those fears—until the recording of Charles on that radio show brought it all back.

Along the way, we also had a lot of laughs. When I fact-checked his rendition of his time at Missouri Valley College, where he said he was head of the Chemistry Department, I reported back that he was the only person in the Chemistry Department and he retorted with a snort of righteousness, “Well, I was still head of the department.”

Another time after I’d interviewed one of his former colleagues, he told me without a hint of hostility, “I know you check up on me.” And I said, “Well, that’s my job. That’s what I do. Nothing personal.” We both knew we wanted the book to be as objective as it could be, given the constraints of time and history.

Of course, he was Charles and stubborn in his own ways. For example, he would never elaborate on his sentiments about his wife, reveal how or where they were engaged, or how he decided she was the one. He kept that private information private, although he did tell me he put his last anniversary card into her casket before they buried her. On some things, he just wouldn’t budge.

There were other things he didn’t want to tell me, and I can’t blame him. For example, he never quite got around to giving me those boxes of documents that outlined in detail the ABC Labs proxy fight that almost cost him the company he’d founded. Those documents and personal notes showed him in a less than glowing light. In fact, I didn’t get those boxes until after his death, with the documents that showed what really happened when ABC Labs nearly went bankrupt, and it wasn’t pretty. Charles could certainly go beyond stubborn at times.

He was a hero, but not a hero without clay feet. No matter what, he was a determined person. The last days of his life, he was still dictating to me what he wanted in the book and what he wanted the book to look like. He also asked me to promise to finish the book, which, unfortunately wasn’t done before he died. I did promise and it took me nearly two more years to finish it. Working on the book after his death I learned some unpleasant facts about Charles, but even the worst of it showed me his courage. He knew those documents would be made a part of the book because we’d agreed it was all going in there. That’s who Charles was. Unflinching. Determined. Persistent. And a bit of a braggart. Yet as the dedication he wrote for this book showed, he was a man who, in the end, cared just as much about the people in his life as the things he’d accomplished. And that’s why his children Jon and Susan asked me to write the book about a man who did indeed come from poverty and a tough background, but who went on to become a successful scientist, entrepreneur, and a beloved family man and friend.

And so I leave you with the introduction Charles wrote a short time before his death:

INTRODUCTION

“I touched the Moon, 4.5 billion years old in space.”

—Charles W. Gehrke, 1917–2009

From the poorest of the poor in the depth of the Depression, Charles W. Gehrke rose to the highest ranks in his scientific profession, going from the melon fields to the moon. During his more than five decades of research, he helped to shape and guide a generation of scientists in solving problems, advancing the academic and corporate worlds. This is a story that needs to be told.

He was right. But it wasn’t the whole story, the whole story is so much more and so much better.

That’s my dedication to Charles W. Gehrke, a man I learned to think of as my friend, as well as my colleague. And that’s a story that needs to be told.