Читать книгу From Melon Fields to Moon Rocks - Dianna Borsi O'Brien - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 2 The Early Days at Home

ОглавлениеCharles Gehrke’s grandfather, Heinrich Gehrke, came to the United States in 1887, deserting the German army to pursue a girl his mother disliked because she hailed from a different village and cleaned houses for a living.

Ignoring both his mother and the German army, Heinrich Gehrke followed the girl to New York City, and they married. He took a job as a blacksmith with a brewery, where workers were entitled to enjoy all the beer they could drink. Unfortunately, as Charles’s sister Lil Gehrke Peairs noted in the family history, this policy led Heinrich to overindulge.

In 1899, Heinrich Gehrke left the United States, taking his daughter (eleven) and his son Heinrich Gehrke Jr. (nine) with him back to Germany. Once there, Heinrich served some jail time as a result of his army desertion. After his release, he operated a blacksmith shop with his brother. A short while later, he and his family visited New York for a few months and then returned to Germany once again, settling in Wremen, in northern Germany, where Heinrich took up shrimp fishing along the mud flats of the North Sea.

The move back to Germany proved to be Heinrich’s undoing. Heinrich began drinking hard liquor and became a harsh husband and father, according to family history. His son Heinrich Gehrke Jr. (Charles’s father) found the elder Heinrich’s treatment unbearable. He joined the German army and, some say, became an accomplished marksman in the artillery despite having one bad eye—a condition Charles would later inherit. On his return home from his military service, Heinrich Sr still expected his son to continue in the family’s shrimp fishing operation without pay.

Heinrich Gehrke Jr. couldn’t take his father’s harsh treatment any longer. He took the money he’d earned from working for other farmers and fled to the United States. In New York City, in 1913, he met Louise Mäder, who, with her sister Lena, had just arrived from the southern German city of Breisach. The two met at a dance and were married.

News of Heinrich Junior’s marriage shocked his mother, according to the family documents.1 When Heinrich Junior’s sister in Germany read the letter announcing his marriage to their mother, she said her daughter was crazy. In the family history, the sentiments expressed in Henrich’s letter are described as: “He was lonely, he saw this girl, he was in love with her, and so he married her.”

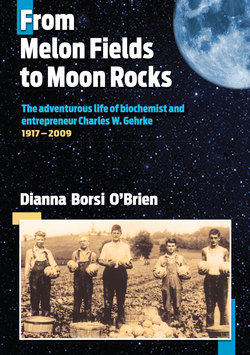

The family history continues, “He later wrote about such a lovely baby they had.” A photo from the time shows an idyllic setting with father, mother, and baby Heinrich, later called Henry or Hank, Charles’s older brother. With Hank born in 1916 and Charles following a year later on July 18, 1917, it looked as if the family was on its way to the American dream.

Already, though, there were hints of Heinrich Gehrke Jr.’s difficult nature. Charles’s official birth certificate reads only “Baby Gehrke,” but in the family Bible, his father listed his name as Karl Wilhelm Frederick Gehrke, giving every German Kaiser a nod. As Charles noted, this wasn’t such a good idea, given the anti-German sentiment in the United States during the years of World War I.

The young family of four traveled to Coshocton, Ohio, to visit Louise Mäder’s relatives. They soon decided to move to the area and take up farming, first buying a farm near Roscoe, Ohio, and then buying a better but smaller thirteen-acre farm on the edge of Canal Lewisville. The new home had a cemetery on one side and a Methodist church behind it, with a small barn, a chicken coop, and an apple tree, as well as space for a vegetable garden. At the end of Charles’s life, his mother’s patch of rhubarb still grew there.

Following in His Father’s Footsteps

At their first home on the edge of town, the family first eked out a living as farmers of a sort, growing strawberries, radishes, potatoes, cabbage, and other vegetables on their few acres of land. Out of the thirteen acres, only three or four turned out to be good, fertile soil, said Charles.

Along with farming the land, the family kept a cow for milk, a horse to help with plowing, and a pig for meat, recalled Charles. He also remembered thinking the barn was haunted because it was next to the cemetery.

In addition to tough economic times, the family faced another problem: Their father was beginning to have his own problems with drinking, following unfortunately in his father’s footsteps. Heinrich Gehrke Jr. began to drink more and more as the family faced the economic problems of the country’s slide into the Great Depression, marked by the stock market crash on October 29, 1929.

Charles said his father wasn’t around much, although he did note with a chuckle he must have been there at times because Lillian (Lil) was born in 1925, followed by Evelyn in 1927, and, finally, Edward in 1929, when Charles was twelve.

Unwilling to dwell on the details, Charles simply said he didn’t like his father much because he was always getting in trouble with the law. For what? “Being obnoxious, I guess,” said Charles. The other children recalled, without bitterness, other memories. For example, Lil remembered, as a four-year-old, seeing her father pin her mother against the wall and hit her as Lil screamed from her high chair, “Leave my mother alone!” Another time, Lil remembered her siblings and herself holding onto their mother’s skirts as they ran to a neighbor’s house for safety. Once, Charles and Hank waited near the grade school in Canal Lewisville with a gun, planning to scare their father off, but Heinrich never came their way that night.

Finally, after one more attack on their mother, the police told their father to leave town and never come back. And for a long time, he didn’t.

A few years later, their father did return, but only briefly. As Lil recalled it, he was so sick and heavy she didn’t recognize him at first. He came to the back door, and she thought it was a neighbor stopping by. Their mother let him in, but he didn’t stay.

The family learned about Heinrich’s 1936 death in New York City a few months after it occurred, when they received his personal effects. The cause of death was noted as cirrhosis of the liver due to alcoholism.

The youngest child, Ed, was seven at the time, and he said he recalled his father’s death only because he remembers his father’s personal belongings arriving in the mail; he wanted his father’s leather wallet. But instead, said Ed, Hank, his oldest brother, snatched it up. It made sense. Without a father on hand, in many ways, Hank took on that role.

Charles said he admired Hank, but he also admitted he always felt dominated by him. Lil recalled Hank urging family members to work hard, sometimes even admonishing them: “What good are you if you don’t work?”

In remarks at Hank’s memorial service in 1999, Charles recalled feelings of tenderness and a sense of teamwork with Hank. “When, on occasion, trouble would arise at school or elsewhere, the two of us met these problems together, thus making our way successfully through many difficult situations.” As for family and work, Charles wrote, “Henry was the leader, as we made our life on the small farm in Canal Lewisville...striving to keep the cellar full....Henry and I were always together, whether hoeing corn ten hours a day, working threshing machines or hay balers, taking wagons full of hay to barn mows....Working with Henry was an experience one never forgets. His work ethic was to do, without fail, a great job.”

A Mother’s Influence

Louise Mäder was born in southern Germany in 1894 to Edward Mäder and Barbara Schmidlin. Edward Mäder, according to the family history, “was an important stable influence on his family and a respected member of the community,” a sharp contrast to Charles’s father.

Louise Mäder worked as a housemaid in nearby Switzerland after graduating from school in Germany but left for the United States at age nineteen, seeking a new life. She and her sister Lena left Germany with one hundred marks in gold from her father, a debt Charles said he later helped his mother to repay.

Upon arriving in the United States, Louise and Lena went to Ohio to visit their uncle, John Schmidlin, who was killed later in an anti-German attack. While Lena decided to stay in Coshocton, Ohio, Louise demonstrated her independent nature by returning to New York City by herself and seeking work there as a housemaid. As previously mentioned, in New York City, she met Heinrich Gehrke Jr. at a dance.

Charles noted that his parents had a troubled marriage. Lil described the family history this way: “Heinrich had been a fisherman in Germany. He was not successful as a farmer in America. During the Depression years, other jobs were difficult to find. He turned to alcohol and was dominated by his need for it.”

When Heinrich was told to leave town, Louise was left with five children to raise on her own. To make ends meet, she began walking to Coshocton, three miles away, to work as a housemaid.

Lil wrote in the family history, “Louise never accepted her current circumstances but always tried to rise above them, no matter how hard or slow. She was a forceful, dynamic, and extraordinary mother who taught her children to always look to the future, that through hard work they could achieve their goals and, as she described, ‘a better way of life.’ ‘Where there is a will there is a way,’ was her belief. Raised with our mother’s firm, austere German ideas and tradition of hard work, frugality and saving, we, her children, are proud of our heritage.”

Ed remarked that complaining about work just didn’t make sense to them. Nearing eighty years old, Ed, the youngest of Charles’s siblings, continued to work on his investment portfolio, manage his many real estate holdings, and write a book about the stock market, when he and his wife weren’t traveling or keeping up their one-hundred-twenty-acre homestead.

“You see,” Ed explained, “we think work is good.” Prior to “retiring,” he’d held the rank of full colonel in the U.S. Air Force, serving as a commander of a Strategic Air Command unit from 1975-1978, the culmination of a military career that included serving as a commander during the Vietnam War.

Like Ed, Charles looked back on his hardworking childhood with pleasure, happily pointing out fields where he once grew rows of strawberry plants and the hills where he picked raspberries for his mother to turn into jellies and jams.

The family garden helped to keep everyone fed, and what the children didn’t eat walking inside from the garden, their mother would can when she returned from cleaning houses in Coshocton.

For the most part, the children took care of each other and stayed out of trouble. As Charles noted, there wasn’t much else to do, with no electricity, no radio, and certainly no television, which wouldn’t become common in American homes for several more decades. The little town of Canal Lewisville boasted almost nothing of interest to do beyond, as Charles recalled, swimming in the river or hanging around one of the two small stores, Corbett’s and Graham’s.

Lil, Ed, and Charles never complained about not having electricity or central heat. Charles made light of relying on a well for water. At age seven or eight, when he was pumping for water in winter, a coating of ice made the handle slick, causing it to slip out of his hands and hit him under the chin. “I can still feel my teeth rattling,” said Charles, with a chuckle, in 2008. The family wouldn’t have running water until they moved to Coshocton in 1935, the year Charles went to college. “That’s why I don’t want to go camping,” Charles said. “The first twenty years of my life was camping.”

The Gehrke home, according to family members, didn’t hold any books, magazines, or newspapers. Rather than reading, the family learned from life and working—and from the gentle guidance of their mother and the example she put forth.