Читать книгу From Melon Fields to Moon Rocks - Dianna Borsi O'Brien - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 5

Ohio State University and the Stadium Scholarship Dormitory

As a result of his teachers’ persuasion and his brother’s help, in fall 1935, Charles stood at the train tracks in Coshocton, waiting for the train to take him to Columbus, Ohio, to attend Ohio State University. “I had eighty dollars in my pocket at the time,” recalled Charles.

He also remembered how much tuition and fees were at the time for Ohio State University: seventy-five dollars a year, twenty-five dollars per quarter.

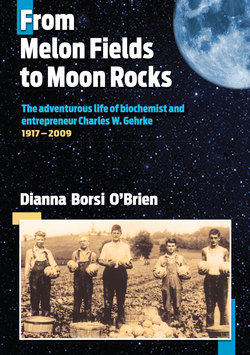

Charles had the money he’d earned from the three or four years of good melon-growing seasons before the Depression hit their produce business. They’d made pretty good money for the times, three to five hundred dollars each summer, and Charles had managed to keep some of the money for himself, after turning over most of it to his mother. Charles had also continued to work as a farmhand after school and on weekends during the school year.

Until he left for Ohio State University, the only trips Charles had taken beyond those areas were with his public-speaking coach Delmar Hoover to Cambridge and Columbus, Ohio.

When he left Coshocton, the only thing he carried with him was a small brown suitcase—and the knowledge that if he needed help, Hank was there for him.

A New World

When Charles arrived in Columbus, Ohio, he didn’t even know where to put the nickel in the streetcar and had to ask the conductor for help. But he knew something more important: how to take care of himself.

In Columbus, it didn’t take Charles long to find a place to live. He and Donald Troendly, a boy he knew from Newcomerstown, near Coshocton, rented the front room in a boarding house, a short distance from the university and only two blocks from the movie theater.

Troendly’s family owned a large farm in Newcomerstown, and Charles had met him through a girl he had been dating from that area. Troendly would later lose his life in France in 1944 during World War II, but in 1935, the two men had other worries.

The rent for the room was fifteen dollars a month, but that didn’t include meals. No stranger to hard work, Charles took a job at a pancake house just a few blocks away, where he could earn a meal or twenty-five cents an hour for washing dishes. He didn’t mind working for his meals, but at six-foot-two-inches, Charles had a good appetite, which the restaurant wasn’t always willing to satisfy. One evening, Charles recalled, he wanted a piece of pie, but they told him it was too expensive. “I wanted my pie,” Charles said, recalling the rebuff.

Back home in Canal Lewisville, things were tough.

Although Hank was working at Clow Pipe Company and making good wages, the family still faced financial problems. While Charles was attending college, his mother had to move the family to a smaller house and give up the truck farm. The family moved four blocks across Canal Lewisville to Liberty Street to yet another home without running water, electricity, or central heat. Despite the diminished size of the home and yard, the family could still grow produce and keep livestock, including pigs for meat and a cow for milk. Their mother continued to preserve and can anything the children didn’t eat on their way into the house from the garden.

By this time, Louise Mäder was in her early forties, and cleaning houses for a living had become difficult for her, so one of the families she had cleaned for helped her get a job with the Edgemont Glove Factory in Coshocton. Still, between working and caring for her family, she had little time or energy for her son in Columbus.

Like many college students, Charles had been sending his laundry home for his mother to do. For a while, Louise Mäder did her son’s laundry, but at one point, she sent him a clear message that she’d had enough: She sent his shirts back to him dirty.

“That was bad,” said Charles. “That wasn’t conducive for relationships.” Charles didn’t take it personally. He knew how much work doing the laundry was because when he’d lived at home, he’d helped with the wash, out in the yard with a scrub board and washtub. His feelings were hurt, but he never mentioned it to anyone. In fact, seventy-three years later, when he found out his sister Lil knew about the incident, he was surprised.

In many ways, making the adjustment to living in Columbus was easy, although at first he found the sheer numbers of students at Ohio State University daunting. He’d graduated from Coshocton High School in a class of 188 students but now found himself among 300 to 500 students in a classroom. He quickly grew used to the situation and took the usual array of classes, including Philosophy of Education and Accounting. Charles also capitalized on what he knew and took German classes, later becoming president of the German Club.

By his second year, his native intelligence and his outgoing nature helped him find a new solution to his money problems. Of course, Hank and his family helped him with money whenever possible, and he repaid them later, one thousand dollars over ten years (and kept copies of those checks all his life). But Charles knew then he needed to ease their financial burden as much as possible.

During his first year at college, Charles learned about the Stadium Scholarship Dorm at Ohio State University. The price was right: one hundred dollars a year for room, which included meals and a seven-dollar-per-year refund at the end of the school year as well. He wasn’t worried about the grade requirement, a B average, but students had to be nominated for the honor of living in the Stadium Scholarship Dorm.

That summer, Charles went to see Bland Stradley, who was then Ohio State University Examiner and Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, lived in Dresden, a town near Coshocton. “I told him I didn’t have any money,” said Charles. The next year, Charles had a place among about three hundred men in the Stadium Scholarship Dorm, where he lived through the remainder of his college career, including the year he studied for his Master’s Degree in Biochemistry and Bacteriology.

The three-story dorms were built into the side of the stadium overlooking the Oletangey River. They featured huge, ward-like rooms where the students slept twenty to a room, their only furnishings one metal cabinet and one cot per person. In between each pair of wards was a study area, and each night, it was lights out at 10:30 p.m.

The dorm was a bargain, but Charles still had to wash dishes. The Stadium Scholarship required students to put in two weeks of kitchen duty every quarter, washing dishes, peeling potatoes, setting the tables, and other such duties.

But Charles didn’t mind. After all, he did without running water and central heat until he came to college, and his farming background held him in good stead; he was used to working hard. At Ohio State University, he held a number of jobs, including working for the National Youth Administration, a federal program that paid students a small sum each month for working at various jobs.

Hard Work Continues

One of Charles’s jobs involved alphabetizing materials for the library, while others were more challenging—even dangerous.

For example, one job as a lab technician involved cleaning the test tubes used in the Bacteriology classes. Students in the classes worked with a wide range of pathogens, such as salmonella, typhoid, diphtheria, and other deadly bacteria. “You name it, it was being taught and used in Pathogenic Bacteriology courses,” Charles said.

Charles’s job involved collecting the trays of used test tubes and carrying them to the autoclave, where they would be sterilized for twenty-four hours at 120 degrees Celsius. The next day he removed the test tubes from the autoclave, took out the cotton plugs, and then rinsed and washed the test tubes in preparation for them to be used again. The danger lay in the possibility of a pathogen ending up on the outside of the test tube and infecting Charles.

Years later, Charles chuckled at his lack of concern, “No one ever me told how dangerous it was.”

Besides, he noted, he earned one hundred dollars a month.

Another job involved using a formaldehyde solution to wash rounds of cheese, roughly twelve-to-eighteen inches high, which were produced by OSU’s dairy technology department. He’d come to learn later that formaldehyde is absorbed through the skin, but at the time, Charles worked without gloves and with no concern at all about the dangers it presented.

One summer, Charles worked in Columbus at Fairmount Creamery, making cherry nut ice cream from leftover ice cream returned by the area drug stores. He would scrape the remaining ice cream from returned ice-cream-counter buckets into a big vat, combing the different flavors and then adding maraschino cherries and nuts, mixing it together to create a concoction known as cherry nut ice cream, a product that, given its origins, he found less than appetizing.

Back home, he found work with Willow Beach Park, an area on the river where people swam. The owners sold sodas and snacks there, and Charles made eighty dollars a summer keeping the place clean.

More Changes

In 1936, Charles also decided it was time to make his name official. When he was born in 1917 in New York City, his birth certificate listed his name as “Male Gerke,” which didn’t even get his last name correct. On his baptismal records, his father paid tribute to the German Kaisers by naming him Karl Frederick Wilhelm Gehrke. But his mother had thought this sounded too German, and with the anti-German sentiment common following World War I, she called her son Charles, the English translation of Karl.

The same year, Charles learned that his father had died in New York City. No one knows where he is buried, although his name is on the tombstone with his wife’s at the cemetery in Canal Lewisville, a burial ground that provides the only reminder of the Methodist church that once stood behind Charles’s early childhood home. Charles said it felt like someone he had hardly known had died. In many ways, this was true. His father had not been in contact with his family since Charles was eleven or twelve, except for one brief visit.

Charles said the main effect his father had on him was a lifelong caution about drinking. “I saw what that kind of thing did,” he said. None of his brothers or sisters display any bitterness about their father’s drinking; his sister Lil joked that her father’s main influence was in creating an entire generation of nonalcoholics.

At OSU, Charles found time for activities beyond his studies. He loved to say that he didn’t letter in swimming but “numeraled” in it and became certified in lifesaving. He also participated in track and attended dances and other campus events, eventually double-dating with his best friend, roommate and study partner Elmer Thomas and finally meeting the woman who would become his lifelong partner.