Читать книгу From Melon Fields to Moon Rocks - Dianna Borsi O'Brien - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

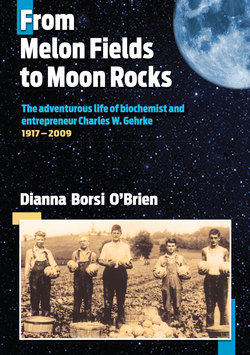

Chapter 1 The Melon Fields

ОглавлениеBy the time Charles Gehrke’s mother died in 1977, she had acquired three houses and enough wealth to leave $17,000 each to three of her five children and property to the other two.

Not bad for a woman who’d arrived in the United States from Germany in 1913 with no money and limited English-language skills and who, by 1929, had five children to care for, without support from her husband.

Louise Mäder Gehrke was not easily deterred. Each day, she walked three miles to a nearby town to clean houses for a living, leaving her three youngest children, Lillian (four), Evelyn (two), and infant Ed in the care of her two older sons, Henry (Hank, thirteen), and Charles (twelve).

The family lived in Canal Lewisville, a small town of roughly five square blocks, in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains in eastern Ohio, near the slightly larger town of Coshocton, Ohio. Named for a portion of the Erie Canal that once flowed through the town, Canal Lewisville was flanked by a river on one side and fertile fields on the other.

While their mother was at work, the two older boys, Charles and Hank, would go to the melon fields to work, putting their baby brother, Ed, under the shade of an old oak tree, which still grows in the field just outside of Coshocton.

When Charles last visited in 2007, corn grew in that field, but Charles could still point out the spot where they put baby Ed to nap in the afternoon while they worked.

For Charles and Hank, childhood was hard work. They labored in the melon fields, soaked up to their waists with pesticides, copper sulfate, lead arsenate, and nicotine sulfate. They weeded acres of corn for ten cents an hour. They sold vegetables door to door in Coshocton from the back of a Model T.

Charles’s least-favorite job was being sent into town to get sugar and flour from an office set up for what passed as welfare during the late 1920s. In later years, he was willing to ask for help, but he never liked asking for a handout.

Many people in rural Ohio and elsewhere were poor. The year Louise became a single mother, the country’s economy was hitting the skids. The stock market crash took place on October 29, 1929.

The Gehrke family faced another obstacle, in addition to poverty. While Charles was growing up, the memories of World War I were still fresh, and anti-German sentiment lingered throughout the communities along the rivers that flowed through the rolling hills of southeastern Ohio.

Charles’s sister Lillian (Lil) said the teacher in the two-story school the Gehrke children attended—who was also the welfare officer’s wife—didn’t even try to teach her to read. Instead, Lil was given crayons and coloring paper. Despite this rocky start in her schooling, Lil went on to earn a Bachelor’s Degree in Education and then spent nine years teaching high school business classes. She is a published author.

Lil said the prejudice against Germans at the time was very real. In the family history she compiled, Lil included a newspaper clipping from February 16, 1921, about an event that family members point to as an example of that anti-German sentiment. The news report recounts the death of a family member as someone who perished several weeks after drinking lye in a suicide attempt.

Gehrke family members recall this death quite differently, saying they were told their uncle died after being dragged out of his shop by some area ruffians and being forced to kiss the United States flag and then drink lye. Whether the printed story or the family recollection is true is unclear. But no one denies the family members kept to themselves in tiny Canal Lewisville, and few other families reached out to them.

Louise Mäder Gehrke equipped her children to overcome anti-German attitudes and other obstacles, instilling in them drive, persistence, a belief in hard work, and a dedication to teamwork and helping others, bolstered by an independent streak. All five of Louise Mäder Gehrke’s children operated on the belief that no matter what you did—whether it was farming, drilling wells, teaching, serving in the military, or raising children—you could do it well and even improve the practice.

Some might call this pride, but there is little evidence of arrogance among the Gehrkes. Most of the time, the Gehrkes demonstrated the midwestern propensity for simply getting on with whatever task was at hand. None of them were prone to tooting their own horns, but Charles came the closest. Charles Gehrke would boast that his lab was the first in the world to automate nearly a dozen procedures for chemical analysis, enabling his staff to do forty or sixty analyses in an hour, versus twenty-four to forty-eight a week. He’d also tell you why he did that work: to automate difficult, time-consuming chemistry so he and other scientists in laboratories throughout the United States would have the time and opportunity to conduct their research better, faster, and more accurately. As Charles put it, “It’s a wonderful thing to open a door for other scientists.”

His drive and work ethic, underscored by hardheaded independence, propelled Charles from a life of hoeing corn and raising melons to a life as a full professor at the University of Missouri, where his scientific research would lead him to be chosen to be among the scientists who analyzed the moon rocks from Apollo 11 through Apollo 17 in the search for signs of life on the Moon.

Charles Gehrke’s work included the development of techniques that sped up analysis by wet chemistry and gas-liquid chromatography, enabling him to analyze the Moon rocks in parts per billion, with amazing selectivity, sensitivity, and accuracy. His conclusion: “There’s no life on the Moon.” All his life, Charles got calls from reporters about his analysis of the Moon rocks. Always a teacher, he offered a full explanation every time.

As an accomplished scientist in the area of chromatography, the science of separating chemicals to analyze everything from fertilizers to DNA, Charles pushed his profession in an unrequited effort to find a way to diagnose and monitor cancer using bodily fluids such as blood and urine, sparing patients invasive and unnecessary treatments.

In 1968, Charles founded a company that, forty years later, would become the anchor tenant in a new research park established by the University of Missouri. Before Charles died in 2009, this company, ABC Labs, had a net income of $2.2 million and employed about three hundred workers, many of whom were University of Missouri graduates.

A federal law in place in 1987 required university professors and U.S. postmasters to leave their jobs at age seventy. After his mandatory retirement, Charles stepped down as Missouri State Chemist, head of MU’s Experiment Station Chemical Laboratories and a Professor of Biochemistry. However, he continued to work, and he traveled the world giving lectures about using chromatography to find cancer markers. He wrote ten books and 270 peer-reviewed scientific papers.

Charles was a hard worker but not a workaholic. A scientist, educator, and an entrepreneur, he was also a devoted family man. He married Virginia Horcher on Christmas Day, 1941, a marriage that lasted until her death on Christmas Day, 2006, their sixty-fifth anniversary.

Their marriage endured a number of tragedies, including the deaths of three children. The couple lost one child just before birth and another just after. Their son, Charles W. Gehrke Jr., died in 1982 at age thirty-five, in a fiery airplane explosion during a U.S. Navy training flight in Pensacola, Florida.

A devoted husband, Charles nursed his wife through years of illnesses, never complaining, rarely seeking help.

A few months after the death of V.G., as Charles liked to call his wife, his son Jon Gehrke and his daughter Susan Gehrke Isaacson embarked on a mission to find a journalist to help their father write a book about his life.

Discussing the potential project, Jon said his father wasn’t just a successful scientist and an important businessman. Jon said, most importantly, his father succeeded as a husband, father, and grandfather. At ninety, Charles could rattle off without a pause the names, birthdates, and ages of all nine of his grandchildren.

It wasn’t just Charles’s success in his field that makes him interesting. Plenty of people come from humble beginnings and make their mark in their professions. Charles was the kind of father who inspired his children to recruit a writer to bring their father’s life to light.

Charles’s commitment to both work and family is what this book is about.