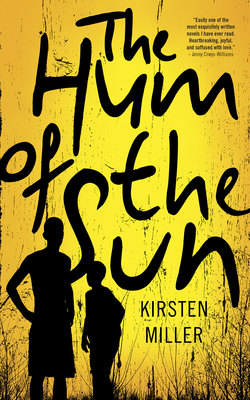

Читать книгу The Hum of the Sun - Kirsten Miller - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

12.

ОглавлениеHe rose late in the morning with the heat on his skin, a fine moisture peppering his top lip. He stood, delirious from hunger, and looked over at the other bed. Zuko was gone.

He found his brother outside in a small dusty bowl near the chicken coop. Zuko’s eyebrows arched perfectly over eyes still slitty from sleep, crusty at the corners. His face angled upwards, as though he was a battery that needed the sun’s rays to recharge.

“You want chicken for your supper tonight?” Ash asked.

Zuko squinted at the sky.

Ash leaned against the coop he’d built with his own hands with wood he’d collected from the surrounding forests. First there were two chickens and now they had six. With the fowls there were sometimes eggs in the mornings. “We have to bury her,” Ash told him. “We can’t leave her there any more. We have to dig a hole, and put her in the ground.”

Zuko made a grinding noise with his teeth. Ash hadn’t seen the kid smile since their mother got sick, apart from a strange grimace when he pushed his nose up close to her body to measure the sweet and cloying scent of her decay. “She’s gone, Zuko. We’ll never see her again, after we bury her. It will be the biggest change you’ll ever know. Nothing . . . nothing will be the same.”

Zuko scraped a foot in the dust. Behind him the chickens scratched. A small cloud billowed before it settled. Zuko moved his body in a slow rocking motion, back and forth.

Later, when Ash fetched the spade from the shed, Zuko was still sitting eyeing the sky and the trees in the cold early sun. “Get up here,” Ash told him. “Help me dig this hole. We’ve got to get it done.”

When Zuko didn’t move, Ash took him by the hand and drew him up from the dust. He put an arm around the smaller boy’s shoulders and led him around the back of the house, up the bank to the pine trees that knotted the ground into some semblance of stability with their roots. Before the trees, he flung the spade down and led Zuko to a tree. “You can sit here,” he said.

Ash’s body tensed, strong and wiry in the way of skin and muscle and bone, yet untouched by the ravages of time.

The earth Ash dug was fresh and soft from the humus made by many seasons of pine needles. His body celebrated the labour, he lost his potential tears through the strain and the sweat and the joy of physical work. Zuko sat by and watched, curious. “Dust to dust,” Ash told the boy as he dug. “We’ll all end up this way.”

The still morning marked the end of a season. A breeze moved through the trees. A crow called above them. Zuko looked up and watched the bird in the nearby branches, hopping with its head at an angle, holding his gaze with an eye like a black bead. Branches caught the sun, and kept them from its glare. Ash dug and sweated for a full two hours before he threw the spade down and stood at the bottom of the rectangular pit. Zuko stood suddenly, and jumped in with him. “Get out! Don’t be crazy, this is your mother’s grave,” Ash told him. A pile of dark earth faced them both at the edge, eye-level. Ash wrapped his arms around Zuko’s hips, hoisted him up, and pushed him by his feet out of the hole.

Later in the day, they walked for twenty minutes and came to a house with two Alsatians running the fence outside. The dogs worked the chicken wire, up and down, barking. Zuko shrunk back. “It’s okay,” Ash told him. “I won’t let them get you.”

A door in the stone house opened and a man appeared, dressed in a shirt the colour of a cornflower, grey trousers and shined shoes. He wore a wooden cross around his neck, hand-carved and hanging from a rusty chain. He reined the dogs in by their collars, attached a chain to each and led them inside. He met the boys at the gate. He rubbed the top of his head with one hand. “Boys,” he said, “I wondered when you’d come.”

“My mother died,” Ash told him.

“I heard yesterday. I meant to stop by your house. Things got ahead of me. I’m sorry for your loss.”

“We buried her today,” Ash said. “I dug the hole, and covered it over. But then I figured it’s not right to do it without some kind of blessing. Will you pray for her?”

“Your mother had no time for God.”

“I want to do something right.”

“The right way would be to report her death. To have had a funeral. To do a proper ritual and feed the community.”

Zuko stood by and watched the door of the house for the dogs. By the boy’s quick eye movements, Ash knew he was ready to run. Ash scratched his head, and realised his hands were stained with the earth he’d dislodged to make that hole he would put his mother into. He couldn’t remember the last time he’d washed himself. He inspected his hands. He put the cleaner hand into his back pocket, and brought out his mother’s ID book. “Please, take it.” He said. He held the small green book out to the man. “Will you report her death? Take care of the paperwork?”

“You should be doing this yourself,” the priest said. “You’re old enough now.”

“We need to get out of here for a while,” Ash said.

“You’ve got a minor with you there. And you’re supposed to be at school. Are you eighteen yet?”

“We’re going to our father. He lives in the city.”

The man fingered the wooden cross around his neck. “When will you be back?”

“I don’t know. I need to tell him that she’s dead.”

The man motioned to the house. “I have a phone inside. You can come in and use it.”

Ash took a step away. Zuko put a hand on his arm absently, as though his thoughts were already off the dog and floating upwards, and he was worried they’d take him with them. “It’s okay,” Ash said. “I don’t have his number anyway.”

“We can find it for you.”

“No . . . I want to see him. I want him to see us. I’ll tell him face to face. We’re his sons.” He didn’t say what he feared most: that his father would turn them away before their journey had even begun.

“What’s his name?”

“Rahl.”

“With skin as pink as a pig’s, I suppose.” The man looked at Ash, sceptical. “Do you know where he lives?”

“I have his address.”

Silence filtered through the sounds of birds. The surrounding trees waited. Beyond the breeze that moved the tops of them, the river rushed. The man looked at his boots, and back at Ash. “Do what you must. I can’t stop you. I can’t feed you either.” He took the small green book that contained the summary of Yanela’s life – her birth date, her number, her photograph. All that was left of her.

“Thank you, sir.” Still Ash didn’t move. Behind the man, in the house, a dog barked. Zuko took a step back.

“I need to let them out now,” the man said. “So, if that will be all . . .”

“We don’t have any money,” Ash said.

The priest looked down as he put his free hand into his pocket. His mouth turned too, as though he’d swallowed something distasteful. He pulled out a roughened note, leaned forward and handed it to Ash. “That’s it,” he said. “I can’t give you any more.” His eyes skipped to the side. “I don’t have it.”

Ash pocketed the money with the hand that wasn’t holding Zuko’s. His brother waited, strangely quiet, watching the ground. The priest retreated into the house. In the tree that overhung the roof with wayward branches, a lone monkey sat and picked at a flea on its belly with one black hand.