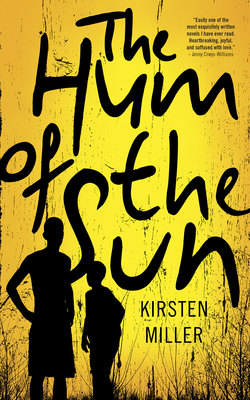

Читать книгу The Hum of the Sun - Kirsten Miller - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

13.

ОглавлениеZuko watched himself coming apart under the pine trees. It couldn’t be helped, but still he worried. It wasn’t, any more, that his mother no longer held his skin together in her tight embraces, or that she rotted away from him now, deep in the ground, in a hole his own brother had dug. A new line had crept between Ash’s eyebrows that threatened permanence. Ash now carried with him a cloud of silence, of separateness, that wrapped him up and kept him apart. When Ash was there, he seemed not there, at the same time. When Zuko made sounds or tried to speak, Ash seemed not to notice. Ash seemed something like his own shadow, or even himself. He existed, and did not exist, at the same moment.

It was Zuko’s own body that wouldn’t do what he wanted it to: carry eggs from the chicken run whole and complete, crack them into a bowl and heat them in a pan over the gas and then put them on a plate for Ash to eat. Instead his body rebelled against his mind, or his mind played tricks on what his body wanted. When his body wanted to help, his mind forgot. It became distracted, and allowed his eyes to play with light, to seek the gaps in the leaves and branches until hours had gone by. Until the trees had faded back, and the negative spaces became what was real. Now that there were no more Cheerios, his anxiety deepened for the changes to come.

It was the circles and the guilt, the light and his immovable body. It was the way his body played tricks on his mind. When his mind and his thoughts were focused and exact with intention and understanding, his body disobeyed. When he wanted his legs to move, his arms took over, waving in the air as though walking the other way around. When he wanted to take the broom and sweep with it, to tidy the mess and dirt in the kitchen that Ash seemed to ignore, he found the broom and he held it, but his arms couldn’t find any sweeping motion in their memory. He could stand for hours, until Ash came in and told him to put the broom down.

He imagined himself as a spirit. If he gave up his own body, as his mother had done, Ash might bury him in the ground too. He’d have nothing but air to float on. There’d be no demand for sound when words no longer mattered. His body would hover, breathless. He’d find the quiet, and it would stay with him. He might look down instead of up, or across at others, and it might not matter any more that he couldn’t move to the places his mind wanted him to go to, or make the sounds that came so easily to other people. He floated out to the back of the house as if he had no legs. He swallowed air particles, as though they were Cheerios, the only nourishment he would one day need. His mother used to tell him to keep his mouth closed, that he looked like a fish, gasping for air, with his mouth open. But that was when she was still on the ground, and not floating out there somewhere, a spirit on the wind as he himself longed to be.

A sound outside came softly, like brushes on a piece of tin. He ran from the house and lifted his eyes. The raindrops cooled his eyeballs before he blinked. It was a game he played with himself, that he might catch the raindrops before they reached the ground. Slowly, he gathered them into the fibres of his shirt. The water and fabric merged into one. They stuck to his skin but he kept his eyes open, as though within them he held the sky’s tears. He blinked rapidly, into the light.