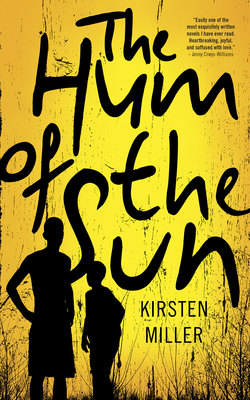

Читать книгу The Hum of the Sun - Kirsten Miller - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

14.

ОглавлениеAsh awoke an hour before dawn. He stared into darkness before he sat up. Through the window the growing light turned the sky from pitch to gentle grey, the trees stamped black against it.

He pushed back the covers and stepped over Zuko’s mattress on the floor. Zuko snored, and turned over. Ash pulled on a pair of jeans and thick socks and the boots his mother had bought him for Christmas with the money the stranger had sent. Sturdy and brown, with the leather laced up in crisscross rows. Ash grew strong in them. As though his footsteps mattered.

In the kitchen he lit a candle and heated water for tea in a pot on the stove. While he waited for it to boil, he sat in the doorway and watched the sky turn green.

When he’d had his tea, he took the last flour from the cupboard and an egg he’d saved from the chickens. He made a rough dough with the sugar that was left in the tin, and shaped it into small rounds. He fried these in a pan in oil over an open flame.

When he’d got Zuko up and dressed, he realised the child had no shoes to speak of. His mother had bought him Christmas shoes also, but with no regular school and no need to walk any distances, Zuko’s feet had grown longer and wider and now he no longer fitted into them. “Damn,” Ash said.

“Da . . .” his brother replied.

Ash looked at him sharply, and saw the gleam in Zuko’s eyes. “You’re only eight,” Ash told him. “Don’t start on the bad language.”

“Da . . .” Zuko said again.

Ash took a small green bag from his mother’s room and packed a piece of still-wrapped soap, a clean pair of underwear for each of them and a jersey for Zuko, though the child seldom seemed to feel the cold. In the kitchen he took a bowl from the cupboard, scooped in the small dough circles fried to a crunch, and added the last milk from the carton. “Here,” he said, placing a spoon in Zuko’s hand. “They’re not Cheerios, but they’re circles and they crunch. Eat. You’ll need the strength.” He brought the old biscuit tin off the shelf and opened it. Inside was a clear plastic packet filled with notes. Without counting the money, he pushed the packet into the pocket of his jeans, along with the box of matches that sat beside the tin.

While his brother ate, Ash packed the rest of the fried dough circles in a plastic margarine tub. He took the last stale half-loaf of bread, already tinged with white mould turning green at the edges, and pushed these into the bag. He fetched an old plastic bottle from the floor beneath the wash basin and filled it with water from the tap. Then he went out into the yard to the chicken coop, and caught three birds in turn. Resisting the urge to hold them, to feel their soft feathers against his face, he wrung each of their necks and placed the bodies into a plastic bag. Back in the house he pushed them into the green bag, on top of the small items of clothing, the bread and the water.

In his mother’s room the sweet, decaying scent of death remained. Her boots waited, open and expectant, on the stone floor. The table held a pile of papers, weighted down with a painted stone. Ash had decorated it for her in years much younger, when she’d had enough money for a tin of paint for the outside of the house. He’d taken a stick and found this stone, dipped the stick into the paint and created a pattern for her. She’d kept it always, this gift from her oldest son. She’d displayed it on the old table her grandfather had made. Now Ash rifled through the papers weighted beneath it. He found copies of her ID book, her father’s will and the deeds for his hand-built house. He found an uncashed cheque for two hundred rand, and a pile of envelopes addressed to his mother sent from a business address, stamped on the back. Most of these were empty. In some was a slip of paper marked “with complements”, and the same business name at the top. They were addressed to a box number in town. He’d fetched most of those envelopes, inserting the small grey key his mother had given to him into the box in the wall outside the post office when he’d done the trip to town to buy potatoes or beans and Zuko’s Cheerios. Sometimes he’d caught a lift home on the back of a donkey cart.

Now he stuffed one of these envelopes into an inside pocket of a soft-lined rain jacket that he took from a hook on the wall. He thought of building a bonfire and burning the sheets, the smell of her death, his mother’s clothes, the boots. He knew it was only his anger that wanted to destroy any trace of what he would never have again. “Come,” he said to Zuko. His brother stood up at the kitchen table. “I don’t know when we’ll be back,” Ash said, as though the younger boy’s eyes had asked. “Maybe never.”

Zuko followed him on bare feet. Ash locked the door with a single key that he placed in his jeans pocket. The surrounding trees bent gently in deference to his decision. They hadn’t gone a few metres beyond the gate when Zuko swung his body low and let out a cry of resistance. Anybody who didn’t know him would have taken it for a protest against being beaten and worse, by his brother. Ash tried to hold on, but it was useless. If Zuko didn’t want to go, there was no making him. Gently, Ash lowered the boy to the ground. “What?” he asked, exasperated. “What?”

Zuko continued to cry, the sound interspersed with an utterance that might have meant “no” to anyone who knew him well. “Nah nah nah!” The boy backtracked to the door of the house and beat the wood with his fist. “Nahnahnahnah!” Ash lowered the green bag and reached into his pocket. The hope his chest contained sank into the pit of his stomach. He walked to the door and put the key into the lock. The key turned; the door opened. Zuko lurched into the house. His eyes cast frantically over the kitchen. He dropped to the floor and scanned the surface beneath the stove and the makeshift shelves.

They found it eventually, under their mother’s bed, its eyes still wide, expectant. The yellow body was fading from being rubbed with his fingers. The plastic seahorse nestled in Zuko’s palm, and the boy’s fingers closed around it. He grinned, the tears still fresh on his cheeks.

“Can we go now?” Ash asked.

Zuko gazed down at the treasured companion in his hand. Both boy and seahorse smiled. Miraculously, Zuko’s feet obeyed his brother.

Outside, Ash locked the door a second time. Above them the trees moved against a white-grey sky. Ash slung the bag over one shoulder and took Zuko’s hand. It was not for the safety or comfort of the child, but to keep himself from crying.