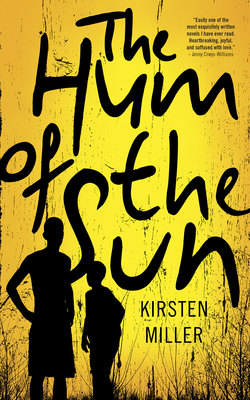

Читать книгу The Hum of the Sun - Kirsten Miller - Страница 23

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

5.

ОглавлениеThe first night they crossed a field and settled behind a koppie large enough to conceal them from the road. They drank the last of the water from the plastic bottle. Ash made a circle of small stones, piled dry sticks and grass into the centre, and lit it to make a fire. While he tended the growing heat, Zuko climbed the hill, favouring his wounded foot. He reached the top and turned around and a kind of laughter bubbled from inside him, a rich and gurgling joy. Ash smiled to himself. The warmth of the young fire glowed on his face.

Zuko stayed at the top of the hill a long time while Ash kept his eyes on the fire. He trusted the first notion of freedom Zuko had known. Somehow he sensed that finally, in this open space, Zuko had found permission to be alive. Ash took the plastic packet that contained the dead chickens from the green bag. Now the birds’ bodies complete with feathers swam deep in the draining blood. The water was gone. Now there was nothing with which to clean the bloody mess.

He called to Zuko on the hill but the boy laughed so hard his body doubled, and then righted itself. “What you so happy about?” Ash muttered. To himself he admitted that, for the first time since his mother died, the weight that previously leaned in hard against his heart had lightened. He too almost laughed at the absurdity of their journey, at their sudden homelessness. It didn’t feel so bad, now they were actually in the world, and nothing looked to harm them. He lowered a whole chicken onto the fire. The flames seared the feathers and charred the skin. When dusk had deepened to darkness, he took a forked stick from the ground and removed the blackened bird from the flames, and placed it on a smooth warm rock. As it cooled, he took off his boots and flung his socks across one of the stones that confined the fire, and he warmed his feet.

Zuko returned when the chicken was cold. Ash pulled off the mess of charred skin and feathers to reveal a tender, creamy, light flesh below. “Here,” he said to Zuko. Ash held out a leg. The boy pursed his lips and turned away. He leaned against Ash’s back and peered into the surrounding dark. “You’ve got to eat,” Ash told him. He put the meat into his own mouth and chewed. Food had never tasted so good. He ate half the chicken and waited for Zuko to get hungry. When the boy still refused to eat Ash dug his fingers into the meat and pulled it from the carcass. He ate until his stomach churned and resisted any more.

He buried the bones and blackened feathers in a shallow grave ten feet from the dwindling fire, and looked around for a bed. He’d brought nothing for them to sleep on, and the only pillows were the stones that surrounded the fireplace. “Come on,” he said to Zuko. “Let’s go and pee.” His brother looked at him. Ash pulled Zuko to his feet. “You’re not going to see a toilet for some time. We’re going to have to get used to doing everything out here in the open.”

Ash paused, facing a nearby tree. He opened his fly and pulled the zip down. He watched Zuko’s face as the child watched him letting loose a thin stream of the water they’d drunk from the bottle that day. “I know I’m bigger than you,” he said, laughing. “But you’ll get there, one day.”

Zuko tried to imitate him, struggling with his own button. Ash pulled up his fly and went behind him, put his arms around the boy’s waist and helped to him undo the button. At the release, Zuko’s small round belly forced the zip down. His penis emerged and along with it, the force of his pent-up stream.

Later, Ash helped Zuko put on the jersey before they lay down. In the dark beside the dying fire, beneath their mother’s jacket that covered his shoulders, Zuko’s whole body shivered. Ash pushed himself closer, to try to let what little warmth that remained in his own body seep through into his brother’s. Ash lay awake throughout the night, while Zuko’s body shook in restless dreams.