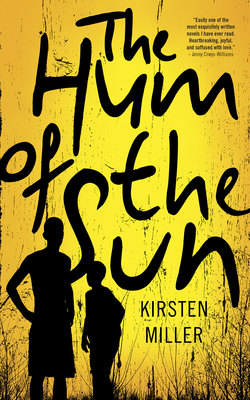

Читать книгу The Hum of the Sun - Kirsten Miller - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1.

ОглавлениеWithin dreams we awaken, and in our waking we dream. Zuko dreamed of singing, but when he opened his mouth there was no sound. He moved his lips. He made shapes that might have formed words, but the utterances that emerged were soft, too guttural, and more like a warble from the throat of a thrush than any song an eight-year-old boy might sing.

Because his mouth wouldn’t move in the way he wanted it to, he took the plate at his elbow and tipped it onto the cold stone floor. The crash sounded, a satisfying smash. A sound that seemed to say, I am here, I am in the world, I have something to express, something that might be a song, if only I could sing.

His capable sounds were reduced to this: the plate, the crash. Enough to summon his mother, Yanela, and bring her running in a way his voice never could.

Yanela hesitated in the doorway as though she might change her mind about the broken crockery and the breakfast and the boy who sat at the table with the voice that wouldn’t work. A beam of sun lay on Zuko’s arm like a blanket. The warmth emitted a frequency like a sound. His lips pressed together: “Mmmm.”

“Zuko.”

If it were possible to utter her name too, he would. Mmmama. Mama. How many times had he tried? How many times had she held his face inches away from her own, her lips softly expropriating that sound, urging him to repeat it? Mmma-Mma. Ma. Ma. Eight years already. He was never more certain than now of his own inadequacies. The biggest yet: his inability to call his own mother by the name that sealed their bond.

“Zuko!” Ash appeared at the door, summoned by the splintering sound. “Shit,” he said.

“Don’t use that language in front of your brother,” Yanela said. “Here, help me to clean it up.”

“He should do it. He broke the plate.”

“He doesn’t have any shoes on. Please, just get the dustpan.”

Zuko wanted to say that he was barefoot because his shoes hurt him. His feet had grown and the old brown canvas pushed too hard on his toes. But they didn’t ask him. And even if they had, he wouldn’t have known the words, or how to say them in any kind of answer. Instead, he put his fingers into the thick air, and they wavered like a conversation in the light of the dusty sun.

Later, he lay on his mother’s bed beside his brother, clutching the yellow plastic seahorse he’d picked up on the road outside the house. It was a cheap toy that might have fallen out of a child’s bucket on the way home from the beach. A small and insignificant cartoon creature – so incidental. An accompaniment to a full day of laughter and conversation and the gentle teasing of a family enjoying a picnic together in the afternoon sun after exploring rock pools. The rounded yellow plastic lay cocooned in the cage of Zuko’s fingers. In convoluted sounds, Zuko told the seahorse the things on his mind. The seahorse stared back at him, eyes wide, smiling without judgement or any attempt to unravel the boy’s sounds. The creature didn’t move or try to get away. Its surprised eyes stared, constant and wide. This thing is mine, Zuko thought. He studied the shape of the seahorse, the focused black pupils and the constant expression. It listened to him always, silent and accepting. Zuko clung to the animal and its plastic consistency, believing that nothing would ever change.